Plaça de les Glòries Catalanes appeared for the first time as a square in 1859 in the Cerdà Plan for the Eixample of Barcelona, submitted to a competition for the expansion of the city, which was considered a pioneering project in the evolution of modern urban planning. The plan aspired to design a city through a square block grid, wide streets with integrated services networks (water, sewage system and gas) and green spaces; to give total priority to the citizens in contrast to the unhealthy situation inside the old city walls.

In this case, the square was conceived as the essential core of the urban network, a big rectangular hole of 9 hectares rotated 30 degrees at the intersection of the three main accesses of the city: Gran Via, Meridiana and Diagonal Avenue. An exception to the regular Cerdà Plan that gives an idea of the important character that has always raised this place. Moreover, its original public and political value can be proved by the fact that in 1905, it was proposed to move the city hall and some cultural facilities into the actual location.

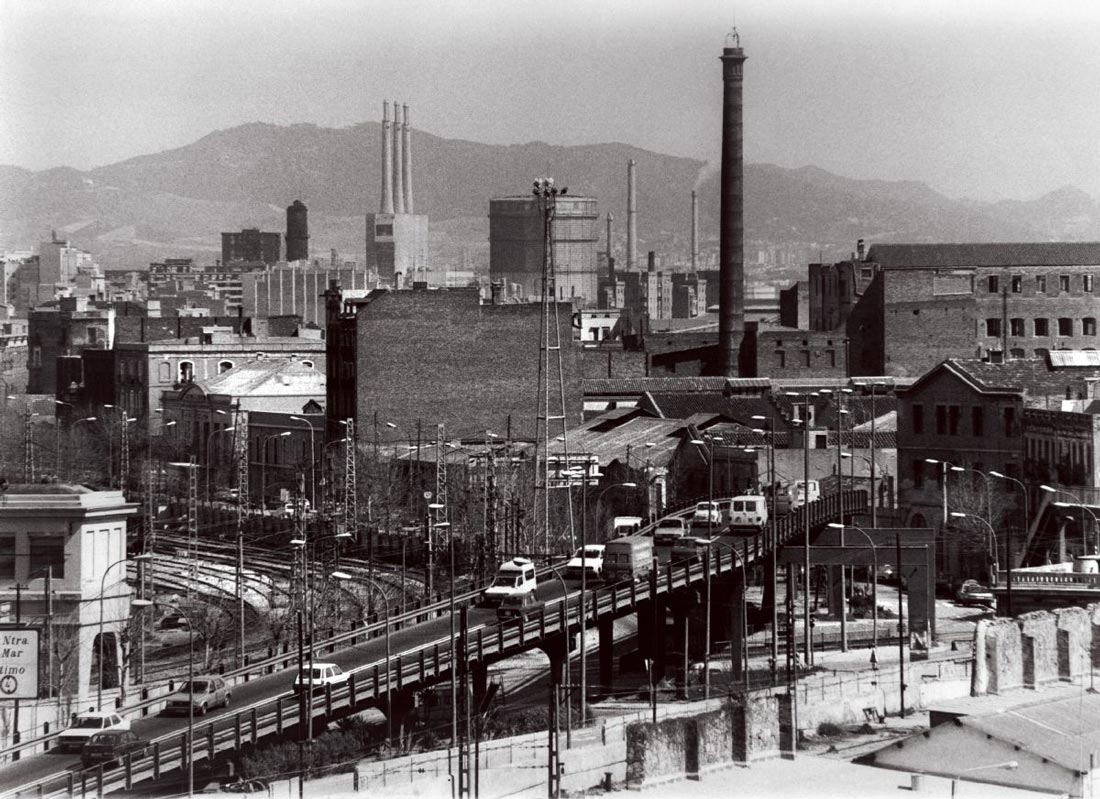

During this period, Barcelona was conceived as a fragmented city with independent towns that would be united by the Eixample grid. The square worked as a connection between the northern residential area of Sant Martí and the southern industrial area. The arrival of the railways in 1852 made it impossible to develop the perimeter of the square but improved the industrial consolidation of the surroundings to the point that it was known as “the Catalan Manchester”, with an increase in the number of factories from 57 to 243 between 1860 and 1888. An important labor movement emerged in the area fueled by a solid class consciousness due to precarious working conditions and the shortage of hygiene and education.

“The Catalan Manchester”, 1932

The increasing labor power in the area was active until the imposition of the fascist dictatorship of Francisco Franco, when associations like Flor de Maig and labor organizations began to disappear. In addition, part of the industrial fabric was relocated to other new industrial areas outside the city. This degradation continued to grow until the arrival of democracy with the first municipal elections in 1979.

In 1919, Plaça de les Glòries was opened as a square to incorporate the old industrial town as a new district of Barcelona. The Poblenou district began a long process of sanitizing and urbanizing the unsafe conditions of both factories and dwellings. The construction of the Encants market in 1928 further characterized the heterogenic scenery of the square, while several factories defined its perimeter.

The arrival of the subway lines in 1951 helped to integrate the district within the city network, but the final urban conversion was reflected in 1953 when the Metropolitan General Plan approved the project to build a circular overpass for vehicles above the railways, in conjunction with the demolition of the existing slums. During the 1970s, the continued increase in vehicle traffic and the complexity of the site were translated into the Metropolitan General Plan in 1976, which reflected the reality of the square as a nodal point in the city and recognized its strategic value.

Plaça de les Glòries, 1961

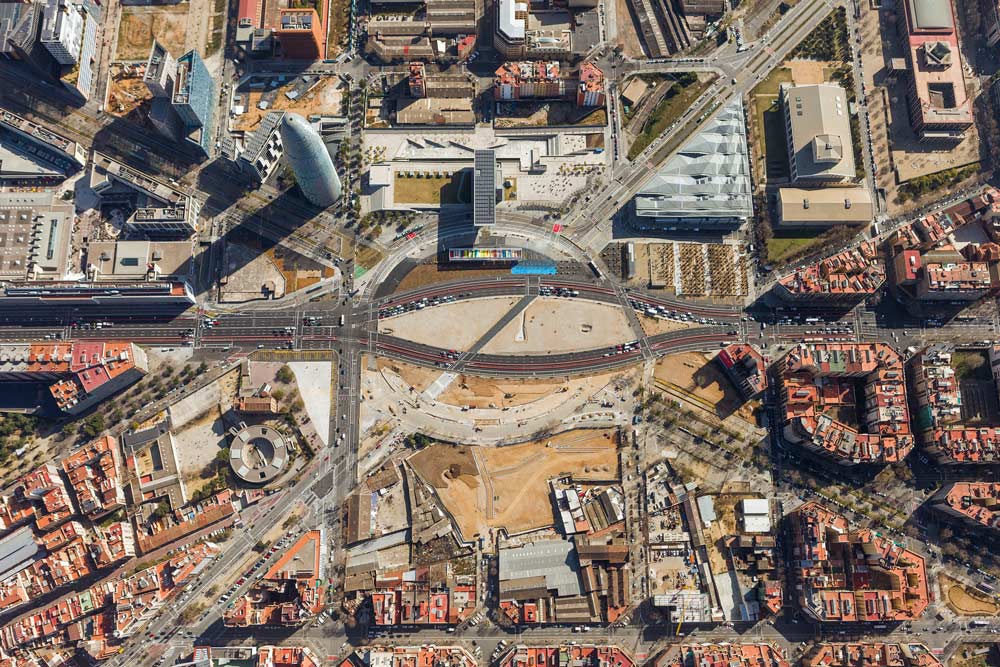

The celebration of the Olympic Games in 1992 was the excuse to enlarge the physical and symbolic scale of the square. The final construction of a double circular overpass for vehicle traffic above an interior park transformed its social and political identity into an infrastructure and a gateway to the city. The transformation of the city continued until 1999, when the last stretch of Avinguda Diagonal was opened, completing the connection with the historical center as well as the opening of the waterfront. The same year, the city council modified the Metropolitan General Plan to transform the Poblenou district and its function.

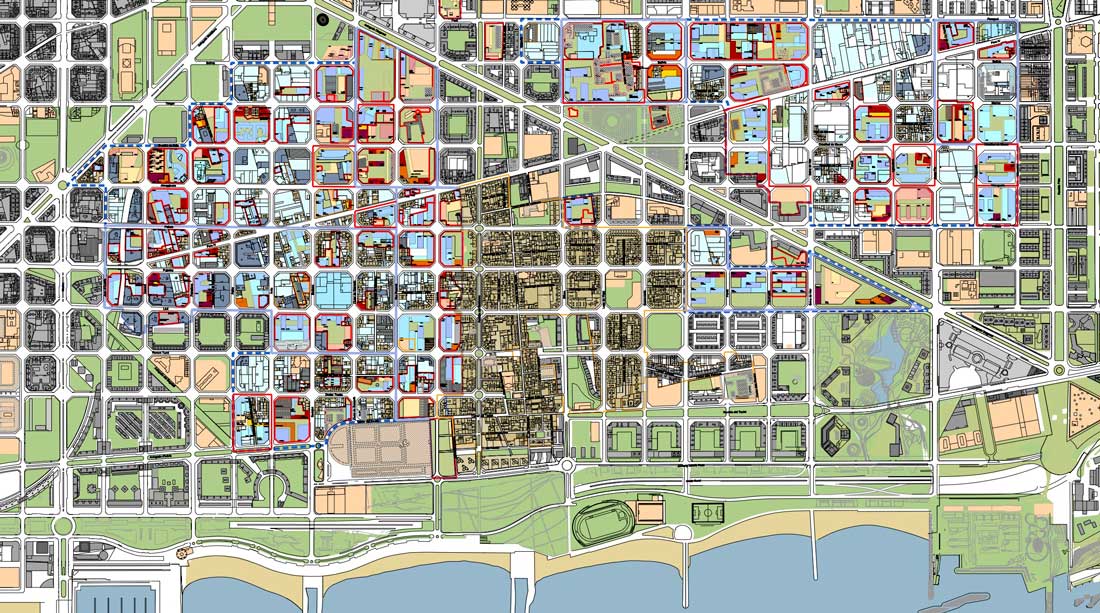

The old factories gave way to Barcelona’s 22@, a new technological district with the goal of combining urban regeneration with economic and social revitalization through the creation of an appealing business atmosphere extended to the international community. However, the physical urban transformation took place before the real social revitalization.

Barcelona 22@ plan, July 2010

During the early years of the implementation of the project, the majority of the industrial land in the surroundings was privately owned. The goal was to provide incentives for landowners to update their properties, while supporting the city’s redevelopment plans. The expected social revitalization had been lagging due to private investments in the majority of the site development plans (78 of 117), since the approval of a new urban planning ordinance in 2000 that had reclassified the district.

The new district of offices grew in seclusion from the local neighborhood, demonstrated by the fact that fewer than 5% of the new jobs created in the 22@ district were occupied by local residents. Although the idea had been to combine the development of the new economy centered on technological knowledge and a network of local workers, designers and artists, post-2000, the reality in the district was the skyrocketing land prices and gentrification associated with the new companies and economic investors.

The situation saw a turning point when the demolition of Can Ricart and part of the district’s industrial heritage was scheduled for 2004. This became the main focus for protests, and several associations banded together to create the platform ”Salvem Can Ricart” (Save Can Ricart). The demands only grew after the expulsion of some artists’ groups from the occupied factories in 2006. These claims forced a change in the City Council’s strategy; the demolition was suspended and a negotiation process began.

Salvem Can Ricard protest, 2005

In 2007, several associations signed an agreement called the Glòries Commission with the City Council to discuss the future of the district and the square. In 2008, the commission had reached two decisions: the complete demolition of the overpass and a the organization of a competition to design the transformation of the square into a public park. That same year, Jean Nouvel built the Agbar Tower on the seafront of the square, and the local government authorized the demolition of the overpass for the following year. A series of iconic buildings began to sprout up around the square: the DHUB Design Museum in 2012 and the new Encants Market in 2013.

The competition promoted by the City Council in 2013 had to “guarantee the centrality of the square, sustainable mobility services, the maximum square meters of green space and the planned housing”.[1] The main achievement, however, as announced by the Mayor Xavier Trias was “to design a new green node for Barcelona, the biggest square of the city”.[2]

These clear intentions for the future of the square have been questioned by one of the figures responsible for the evolution of the city since the Olympic Games: the architect and urbanist Josep Antonio Acebillo. He defended the concept of “centrality” and affirmed that a “superficial” reform would be a big error. “In large urban projects on the metropolitan level there are clearly three stages. The first one is the discussion of the system; the second one is the infrastructure; and the third one is about architecture and landscape.” He emphasizes that the City Council has been focused only on the third one, simply wondering “how many trees will be planted and where”.[3]

The political pressure of the social demands led to this lack of a necessary debate, which was passed over by the reductionist bases of the competition, focused only on the final result. Therefore, the jury made up of 12 professionals and 2 neighborhood managers was conceived essentially for show, to choose among 10 proposals with the same basic urban strategies. The members were representatives of all the City Council departments related to housing, several professionals from the architecture and engineering fields, and with the special evaluation of the well-known architect Josep Lluís Mateo.

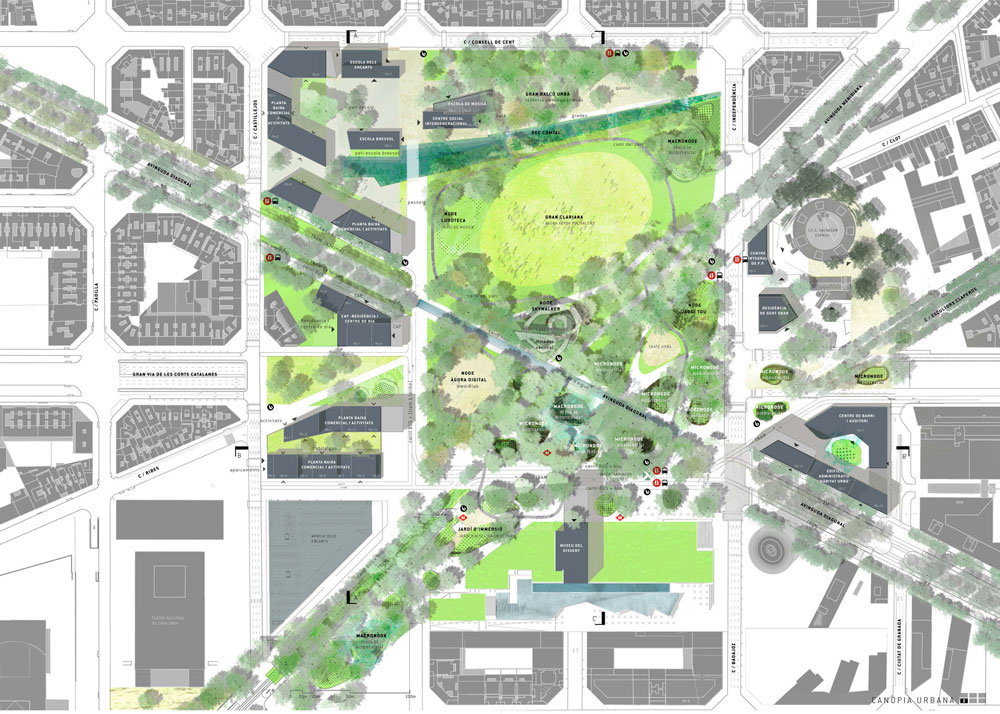

The “Canòpia Urbana” (Urban Canopy) by UTE Agence Ter & Ana Coello De Llobet was announced as the winning proposal in February 2014. It constitutes a natural “green lung”[4] covering 13 hectares. Avinguda Diagonal crosses the square as a pedestrian route, and the underground connections concentrated on the southern side of the square to allow for the big park in the northern area. The project also includes the creation of several public facilities and the total traffic infrastructure buried underground. The proposal listed a minimum cost of €29.9 million, with six different phases to be carried out between 2015 and 2018.

At this point, it is important to point out all the actors (public and private) who are involved. The principal political actor is the City Council as the main developer of the remodeling project, in response to the neighborhood pressure against privatization, and ADIF (Administration of Rail Infrastructures) owned by the Spanish Government plays an important role on the construction of the new station. The other actors are private: financial institutions and construction companies responsible for the new housing that has been criticized due to suspicions of speculation on the part of the City Council, which was seen in the case of the housing development for the “Fòrum Universal de les Cultures” in 2004.

For almost a century, the specific location of the square has undergone a continuous process of transformation, redefining its configuration several times by combining functions and scales. In these terms, it is important to make a comparison in size between Plaça de Catalunya, situated on the historical border of the old city walls, and “Plaça de les Glòries”, which has been reshaped as a void inside the Eixample grid without an urban identity. Both squares are characterized by the central role they play inside the city network.

This status as a void inside the grid could remind us of Central Park in New York City, but it is important not to forget the original meaning of this space, as explained by the architect and urbanist Manuel de Solà Morales: “Why do we need more green spaces?” he asked himself. He explained that the center of New York City is not Central Park, but Times Square, with its cars and the intensity of its urban life. Solà claimed that the solutions proposed so far were reductionist and only seemed to have taken into account the traffic. “First we must know what we want for Glòries; then, the cars will go by on one side or the other”.[5] According to Josep Antonio Acebillo: “There is too much space in Glòries. There is a lack of density. In my opinion, Glòries is not a place for a Central Park, because that situation was not foreseen in the Cerdà Plan”.[6]

These references emphasizes the critical stances taken on by architects and urbanists outside official institutions since the definition of the future square was announced by the competition organization. Among the 10 proposals presented it is easy to identify the winner because of its ambiguous definition enlarging the green character with a continuous flow of trees, but without any urban strategy on its immediate perimeter. This open character takes the risk of losing its centrality for the city. The park was meant to become a “place of intersection of trends, culture, knowledge, design and people”,[7] rather than a green superficial area that covers the underground system of railways and traffic.

In his book Image of the City (1960), Kevin Lynch describes the identity of a place within the city when he writes that “nothing is experienced by itself, but always in relationship with the surroundings” and that, “every citizen has long associations with some parts of the city, and its image is soaked in memories and meanings”.[8] Therefore, the determining factor that will lend it meaning as a public space will be the surrounding activity and its relation with the citizens.

Plan of the winning proposal Canòpia Urbana by UTE Agence TER & Ana Coello de Llobet, 2014

Plaça de les Glòries is being prepared to embrace the central urban role it was assigned by Ildefons Cerdà 150 years ago, but it won’t be able to get back its identity as a public square anymore. The analysis of the initial idea of the innovative Barcelona 22@ project to bring together the local and international communities in the same district led to the mutation of a paradigmatic square from its original political and social sense to a mere space of recreation. It became an example of the new reality of Barcelona: a city focused on the strength of economic lobbies and tourism strategies.

Therefore, the question remains as to who will be the real beneficiary of this complex and expensive project of transforming the historic square: the official institution interested in globalization and the international image of Barcelona; or the social agenda, which deals with the responsibility of the administration to provide ample public spaces in terms of self-representation for the citizens.

In political terms, these large spaces are always subject to public discussion. So, the transformation of the square into a park, through infrastructure, goes further than just a political decision to add more green space to the city. While the City Council is spending a huge amount of money on the traffic transformation of the square, strongly demanded by the neighborhood over the past decades, we should also consider the consequences of the populist argument of having a park as a social space. In fact, the ambiguity of this space contradicts the meaning of a social space as defined by Henri Lefebvre: “Mediations and mediators have to be taken into consideration: the action of groups, the factors within knowledge, within identity or within the domain of representation. Social space contains a great diversity of objects, both natural and social, including the networks and pathways which facilitate the exchange of material things and information“.[9]

The constant struggle by the district associations to keep the local and worker identity gives the impression that the City Council took advantage of the instability of the current social situation to push through the fast development of those projects that would provide an increase of capital and representation.

Understanding this complex and polemic process, one has to consider the mayor’s allegations, saying that “we have fulfilled a dream that Ildefons Cerdà began”,[10] when it is clear that the pressure of the socio-political demands led to the rapid deliberation of the competition. But most of all, these political and social circumstances confirm an alarming lack of a theoretical and academic debate, which is a proof of the tendency of the official institution to collect new architectural happenings, without taking into account the efforts made by the administration and professionals since the Olympic Games toward an understanding of the city as a whole as a comprehensive project.

To conclude, it appears that the real concern of the political managers of Barcelona is not to think critically about the nature of one of the most important and representative squares in the city, even though its history demands a better and more accurate resolution. The future park denies the overall political and social meaning of Glòries as an urban space and turns its back on the real public and collective values for capitalist interests. Unfortunately, the citizens have quickly accepted the new idealistic image of a shiny forest within the city that clearly exemplifies Guy Debord’s observations of modern societies: “where modern conditions of production prevail, all of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacle”.[11]