As Heather Davis and Zoe Todd remind us, human-induced environmental damage is not a recent event, but a continuation of colonialism and its “practices of dispossession and genocide, coupled with a literal transformation of the environment, that have been at work for the last five hundred years.”[1] Building, land use, and urbanization have been instruments of this global expansion of colonialism, modernization and capitalism, contributing to the loss of diverse human cultures and their traditions, as well as the diversity of the Earth’s ecologies that had been home to those societies. As the geographer Kathryn Yusoff writes: “The Anthropocene as a new rendering of time, subjectivity and agency announces both a break in and consolidation of modernity’s temporal arc.”[2] Could the present moment of reckoning be a potential turning point?

In the 2021-22 academic year, we encouraged a group of thesis students in Undergraduate Architecture at the Pratt Institute in New York to imagine what this turning point could perhaps look like. Together we investigated a different role for design through a series of overlapping inquiries:

1. How can we understand socio-economic reparations in spatial terms?

Sites for spatial reparations are those characterized by multiple forms and scales of violence that have affected human societies and the shared environment of both humans and other species. Addressing these sites requires a long and critical view of history, and an understanding of what sustains or damages life in the complex relationships between all animate beings.

2. What are the temporal scales of repair at which design can operate?

Our group worked with overlapping notions of time: the longue durée of human habitation and cultures, the relatively short history of European expansion and modernization, and the slow violence of environmental toxicity and multi-generational human trauma. What sort of temporal response does the possibility of reparations require?

3. How do we identify instances of slow violence and actively address them?

Environmental damage is often not perceivable. Rob Nixon uses the term “slow violence” to describe the invisible, incremental damage that disproportionately affects disadvantaged populations, not just in space but also over time. This includes the erasure of cultures through gradual uninhabitability and toxicity. We examined ways to identify and represent this violence, create accountability, and resist the idea that it is “inevitable”.

4. Can we think of care as the primary purpose of our large-scale infrastructural, mid-scale urban, and small-scale community building?

The Covid-19 pandemic has made the need to acknowledge our mutual interdependence and vulnerabilities more urgent than ever. In our current social environments, great attention is paid to the legal and productive body of the citizen, but little protection is provided for the physical body and the psyche. We believe care needs to be valued and shared; this needs to be done at multiple scales and challenged through multiple platforms. How can we identify and address institutional and structural trauma, and spatialize places of healing? Can we shift from a prevalent culture of production to one of reproduction?

5. How do we address the cumulative effect of crises?

Mary Annaïse Heglar recently wrote that we live in an age of “crisis conglomeration”.[3] It is no longer acceptable to look at any crisis (whether health, climate, or migration) through a single lens. We explored ways to represent how crises overlap and investigated their roots in order to actively propose responses.

6. Are we prepared to embrace degrowth with our current set of tools as designers?

Degrowth is an idea that critiques a global capitalist system that pursues growth at all costs. The concept of degrowth strives for a self-determined life in dignity for all, as well as an economy and a society that sustains the natural basis of life. This entails a reduction of production and consumption in the global North, and liberation from the one-sided Western paradigm of development.

The Americas as site:

The great cultural and ecological diversity of the Americas, with large continuous landmasses and small island nations, megacities and areas with almost no human habitation, and its shared history of European colonization and slavery, make it a rich and relevant site for consideration. Our thesis students considered comparative cultural, historical, ecological, and social histories within this large region, as well as specific local conditions in sites ranging from the Peruvian rainforest to urban Detroit.

Methodologies

We engaged in research that inevitably draws from Western disciplines: cartography, geology, anthropology, etc. We explored ways to learn from and challenge these realms of knowledge, as well as potentially produce new forms of inquiry.

We emphasized the study of multiple scales of time, including geological, historical, biological, and political spans. Mapping the past was intimately connected to mapping the future.

Students investigated their potential site selections by performing exercises in cartography, starting from analyses of historical maps of colonization and settlement, land appropriation and division, and related economies and ecologies, and then borrowing techniques from Radical Cartography to construct an argument around each project site.

Writing was used as a generative process through which to explore lines of inquiry and to produce critical narratives of the past that can influence alternative potential futures.

The projects below examine overlapping issues including environmental degradation, urban disinvestment, food, transportation, and healthcare deserts, racial injustice, and women’s rights. Students used experimental methods of charting history and space to understand the complexities of their site in the present and to begin to imagine the mapping of different futures. In doing so, the students explored a number of current approaches, including reparations, degrowth, care and participation, and environmental remediation.

Invisible Realities of Future-Past

Location: Detroit

Students: Cierra Francillon + Caleb-Joshua Spring

Winner of Best Degree Project of 2022 Pratt SoA

Runner-Up Social Justice Award Pratt SoA

Located in Detroit, Black Bottom and Paradise Valley were social and cultural meccas, a symbolic center of Black life. This place was one of the major destinations of the Great Migration of the 20th century, a mass exodus of Black people fleeing the intense racism in the South in search of better opportunities. Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, which were significant centers of African American life, were razed by the city of Detroit and state of Michigan for urban renewal and to construct the Chrysler Freeway (I- 375), displacing large numbers of Black people and creating root shock in the Black community that has present-day ramifications.

This project is rooted in the exploration of the dispossession and subsequent root shock caused by the American highway system and urban renewal. This project seeks to rectify the effects of “root shock”[4] by imagining a parallel present where Paradise Valley and Black Bottom re-emerge and are allowed to grow without disruption from the effects of white supremacist policies. The goal is to speculate on a new way of Black urban life, or a new Black Commons, by dissolving the highway system to return the commons to Black people and accessing this parallel reality that is rooted in the legacies of Black Bottom and Paradise Valley. The domestic commons, the commons of sustenance, the commons of cultural production and leisure, and the space of the collective are new typologies that lean on music, ritual, care, and agriculture, to restore Paradise Valley and Black Bottom as cultural and social meccas in Detroit. We used an Afrosurrealist approach to encourage, support and allow for a rhizome of personal relationships spanning across Africa and North America in order to reimagine and reform a Black Detroit in the crux of the interstate highway system and urban renewal. As the highway system crumbles into disrepair and is abandoned, a new Black Commons will emerge from the ruins of late-stage capitalism and its anti-black policies.

Line of Action: Unfolding Cycles of Placemaking

Location: Kansas City, MO & Recife, Brazil

Students: Beatriz Xavier + Michelle Singer

Honorable Mention as Best Degree Project of 2022 Pratt SoA

Runner-Up Social Justice Award Pratt SoA

The traditional practices of border drawing and mapmaking negate the experiential, the three-dimensional, and subjective experience of humanity. Therefore, the stewardship and radical design of boundaries, borders, and waters’ edges can be something of a rebellion, and they have the potential to disrupt the geometric and oppressive systems implanted by white settler-colonialism.

We ask: How can we radically occupy the residual spaces that the grid could not reach, where it disintegrated, and what it left out? Many projects have studied the historical segregation of colonial cities, but few look to the regions in between, generated by centuries of settler-colonialism. The act of paving gridded streets into divided terrain was only possible where the land was flat enough to colonize. But what happens to the terrain labeled as “impassable” on official maps? These landscapes cannot be subdivided and paved over.

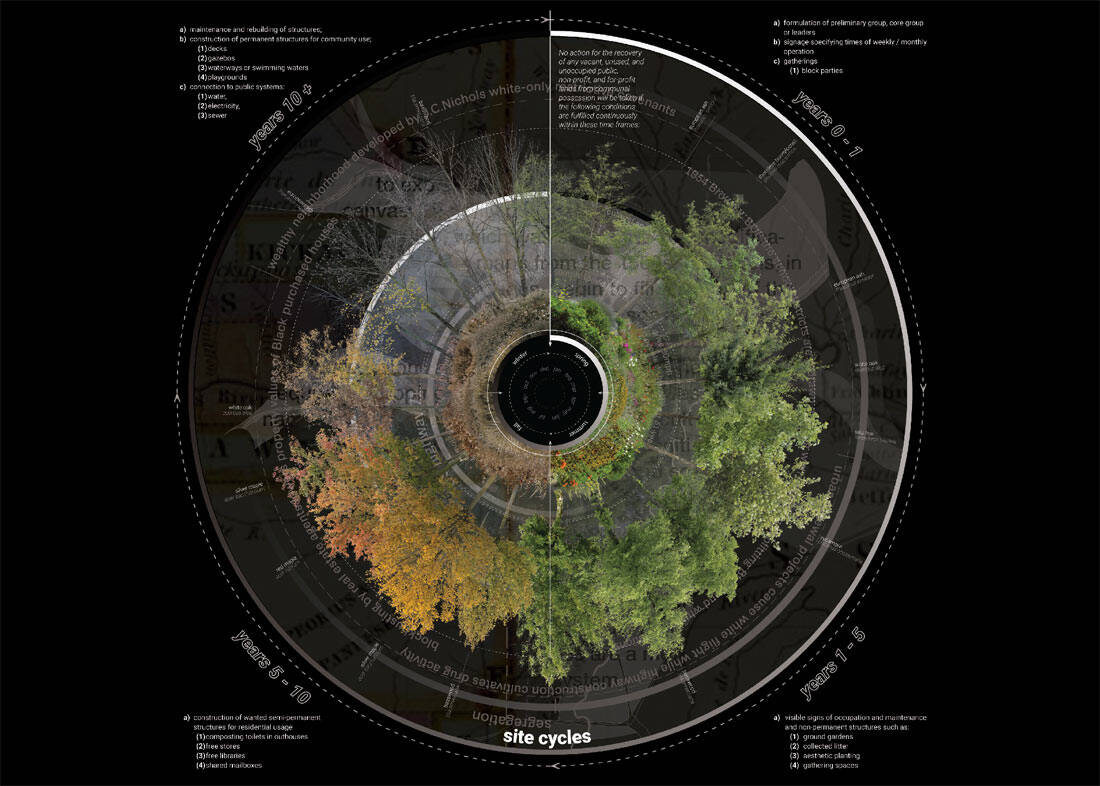

Engaging these in-between spaces as means of action and placemaking can address unseen histories of the ancient past while acknowledging the prevailing struggles of the current moment. Through methods of folding the urban grid for the reclamation of communal land, our project establishes a framework for the collective use, inhabitation, and eventual co-stewardship of spaces. We propose legislation that allows for collective action to undermine biased authorities that approve land use. We take from the concept of adverse possession – squatter’s rights – to create a direct pathway to collective stewardship, providing a suggestive framework for communities to reclaim abandoned lots and parceled land without a seal of approval.

Our research unfolds in liminal cities of our ancestry: Kansas City, Missouri and Recife, Brazil. These sites become case studies that reflect one another in two parallel worlds of colonization where we have familial ties. Designing connections and stitching together geometric interventions, we introduce a suggestive framework that is potentially adaptive to cities across the Americas.

Encoded Cities of Co-Existing Histories

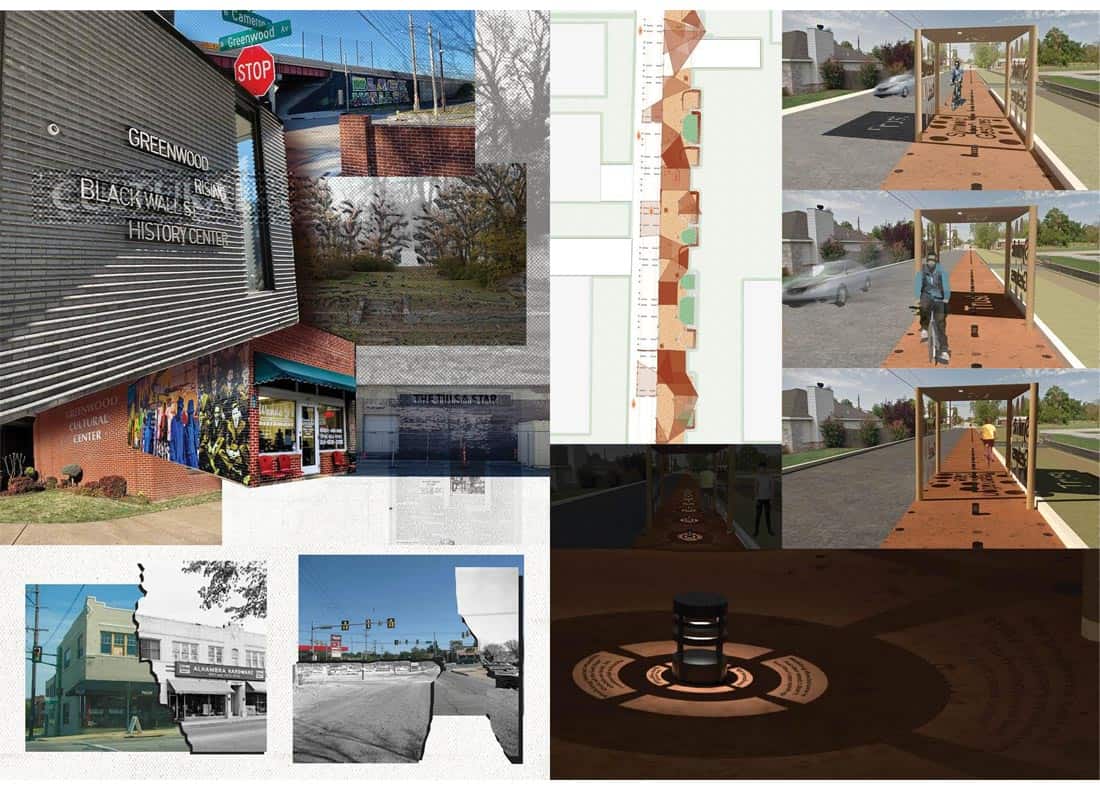

Location: North Tulsa, Oklahoma

Students: Jared Rice + Nengi Njere

Winner Social Justice Award Pratt SoA

There are many intertwined Black and Native traumas present in Tulsa, Oklahoma. When addressing the repercussions of Native land having been acquired from Land Rushes, the Trail of Tears and their Black slaves, the Tulsa Race Massacre, the destruction caused by Urban Renewal efforts, and the personal scaled violences in between, the victims are often historically implicated in also directly imposing the violence and continuing trauma patterns. In these situations, separating compounded and ongoing direct traumas, structural and potentially indirect traumas, and the legacies of historical traumas can become difficult.

To properly understand this, we began constructing archives and finding cultural artifacts through research and speaking with native Tulsans. This began to unearth how these ideals became embedded and encoded into the social and structural infrastructures of Tulsa. From this research emerged a language system that would make proposals accessible to resident stakeholders. Our proposals integrated various archival histories, persistent cultural textures and markers, and dynamic new typologies founded from familiar cultural practices.

Reparation for the layered violences and their unfolding legacies must complicate any unified single narrative between communities as an answer and instead embrace the contradiction of coexistence. Through 1) decoding the communal, intracommunal, and intrapersonal traumas, 2) decoding and foregrounding layered oppression forms, 3) overtly validating various expression methods, and 4) destigmatizing avenues towards therapy, our interventions seek to afford greater expression and agency for the communities.

Our designs blend urban planning and interventionist approaches to construct transhistoric and ever-evolving design solutions, transforming public spaces into localized and engaging cultural/personal story archives and memorials. This intersection of story-centric design and degrowth embraces Native multi-generational ecological methods and reuse/sustainable methods from Black communities, among other practices. Only through the continued centering of authentic input of past and present can any successful, long-standing future reality be created.

A New Public Domesticity

Location: Port of Spain & Lima

Students: Maria-Eleni Beriou + Julia Mendyk

This project seeks to bring the domestic realm into the public sphere by addressing alternative histories as experienced by women in the private sphere. We present these histories through our research on Trinidad and Tobago and Peru. Both sites have colonial histories which continue to frame gender affairs and violence within their societies. Due to their extractive economy and culture of violence, we are looking at Trinidad and Tobago and Peru as examples to study conflict in both the domestic and public spheres. Both countries have experienced the dissipation of care, which has been overshadowed by the exploitation of the environment because of extractive practices, and the exploitation of women, familial structures, and domesticity.

Our approach to this project is one that recognizes care as a force that operates along every distinct scale of life. We propose small-scale programmatic plug-ins that highlight the power of care in everyday activities. They allow local political participation through programs integrated in the daily routine of the occupants, such as the market or the community laundry. We are proposing to isolate and minimize friction within a community by creating places of gathering that turn into spaces of social and political importance. They give women and indigenous peoples agency over conflict and societies that held them in the background.

The plug-ins we are proposing are not large-scale interventions but small-scale insertions of archetypes that complement existing site conditions. The archetypes are meant to bring what is behind closed doors into the public realm. They promote access to the type of care a mother would share with her child, as well as allowing for a transparency of the conflicts commonly happening within the private realm of the domestic and political spheres.

For the future, we hope that our project of archetypal care interventions can be implemented within a variety of sites and can foster care through the everyday activities that can occur within them.

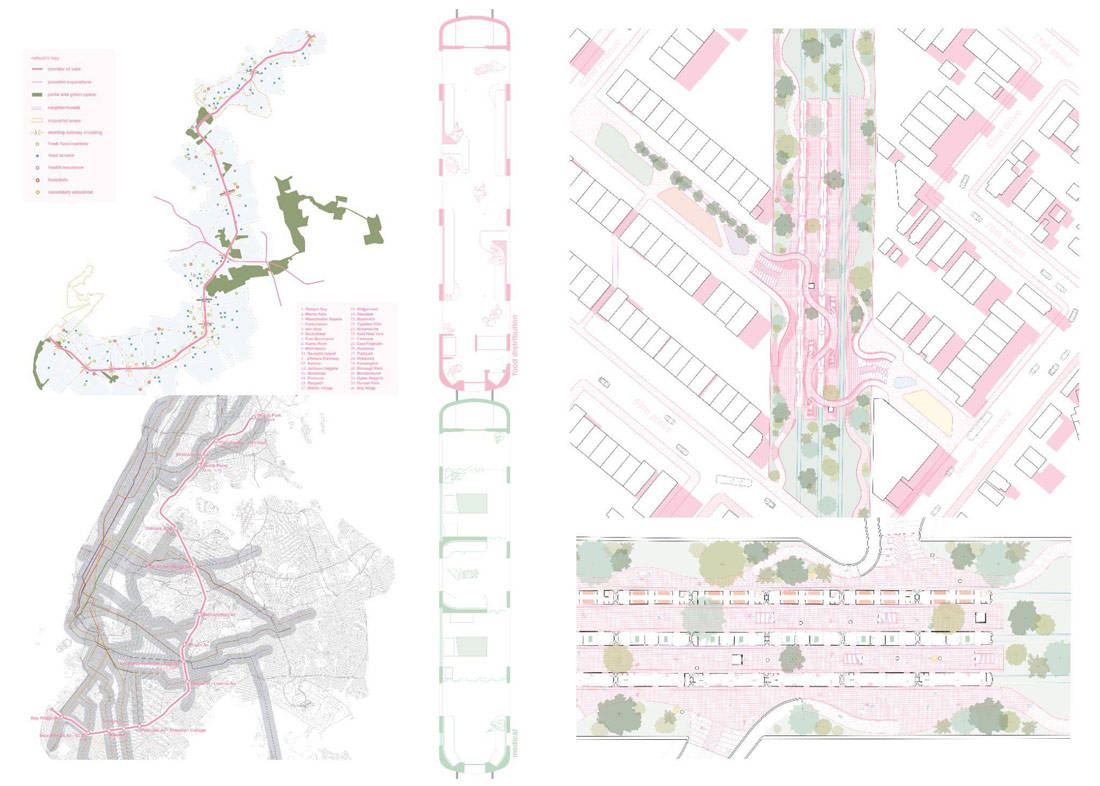

The Corridor of Care

Location: New York City, USA

Student: Joe Shiveley

The New York City subway and its precursors demonstrate a pattern of inconsistency in their histories: the juxtaposition between considerable expansion and innovation and periods of financial distress, violence, and fear. These histories are tied to numerous policies of disinvestment throughout lower-income neighborhoods, denying large swathes of the population the transit to which they have a right.

The Corridor of Care is a reclamation of extorted and exploited soils, ameliorated by a synthesis of systems – a mobilities network of interrelated programs that provides access to the critical facets of urban life from which the city has disinvested in much of Central Brooklyn, Queens, and the South Bronx. This project aims to pull away from capitalist planning conventions in order to equip New Yorkers with their own agency and distribute care more evenly across the city. Individual agency is contingent upon safety and accessibility. Graphic and wayfinding methodologies must be tuned in to the understanding that all bodies are different.

This project involves trans-scalar programmatic activities that consist of mobile and in situ components organized in three categories: cooperative care, health, and regenerative ecologies. Stretching programs between neighborhoods along the corridor alters the behavior of each ride beyond that of the idle commute to generate a network of care and restorative actions. Our capability to destroy is evident, but with that we have the capacity to repair and prosper. The solution is not one of great technological advancement or complexity but is quite simple: care. Caring for one another, caring about our impact, caring about the plants and animals around us, and caring about the future. The Corridor of Care aspires to a future in which a homeostasis is restored and indigenous perspectives are once again recognized – one we all have a hand in and one we all are a part of.

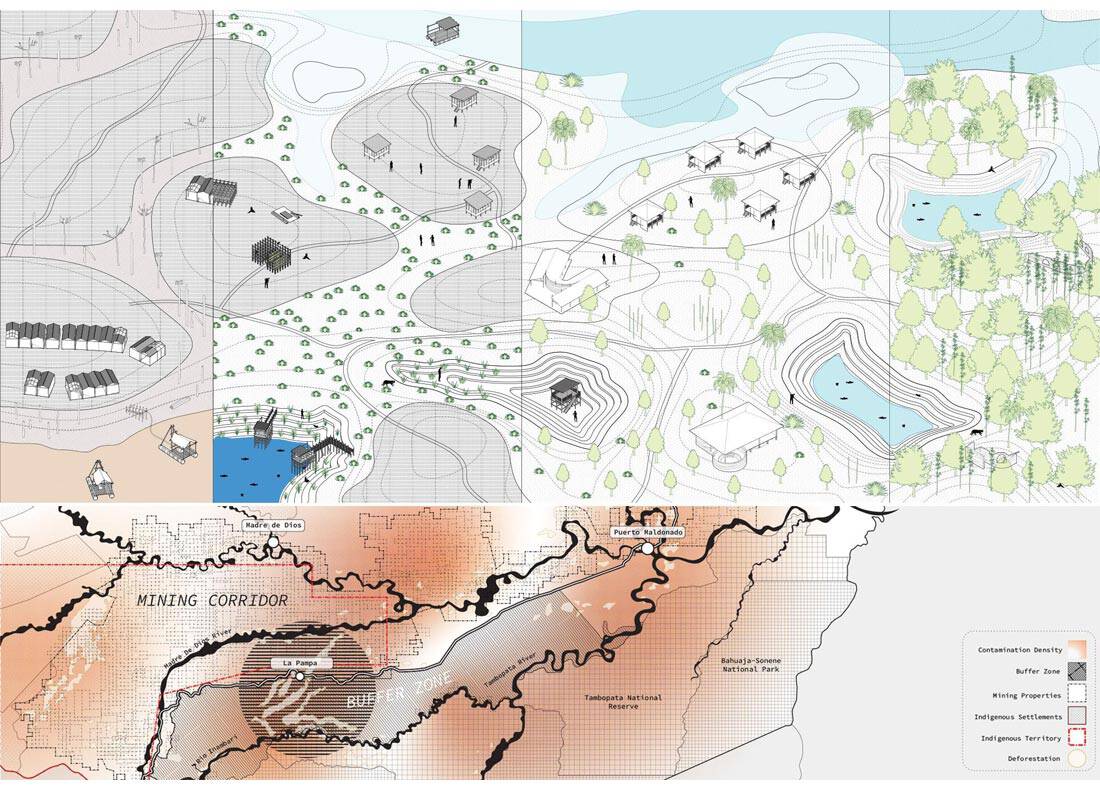

Post-Extractive Communities: Decolonized Infrastructure

Location: Peru, Madre de Dios

Students: Beril Kolsal + Constantino Aristizabal

Nominated for the Pratt SoA Climate Crisis Prize

Post-Extractive Communities is an investigation that addresses environmental inequalities in the Amazon rainforest by healing and empowering local and indigenous communities in an ecosystem that has been affected by gold mining, pollution, and deforestation. The area of interest is located in Madre de Dios, a department in southwestern Peru characterized by dense stretches of primal forest and complex underground and surface water systems that feed the wider Amazon river basin. Madre de Dios is a remote location, where the government has historically struggled to respond with support in a timely manner when shortages and crises ensue. Alluvial gold mining in the Pampa region of Madre de Dios is the cause of an accelerating rate of deforestation and the contamination of important bodies of water. Cyanide and methylmercury are released into the environment through air and water in the extraction process of gold. These substances affect the wildlife, filter into the food chain, and poison the sources of water that provide for human populations across the entire region. Corruption, neoliberal trends, general neglect, and policymaking in favor of extractive practice have aggravated the crisis.

We generated a hypothetical timeline of what could occur in the next 150 years of the extraction process: the desertion of mines and reclamation, detoxification, and reforestation of the areas affected. We formulated a solution rooted in ecotourism as a way to benefit the affected communities and guide economic growth and degrowth in an effort to reach a balance of human activity and environmental protection. At the core of our investigation lies a question that has been asked by many through every stage of human civilization: what is the role of humans in nature? Is this perceived dichotomy one and the same? By taking an optimistic position towards environmental regeneration, we make a case for human and nature co-habitation and sustainable practice.