Books about Mexican architecture rarely mention the real conditions underlying construction: for example, in the capital the earth trembles, the city is built over what used to be a lake, rainwater is sent to drainage systems and causes repeated flooding, and distant rivers are drained dry to serve a population that complains about breathing polluted air and builds more parking lots than schools, hospitals, or parks. How should the buildings in a city that moves, sinks, and floods be? What sense does it make to talk about architecture when there are no plans regarding its links to services? What is the relationship between a building, the conditions of the territory, and peoples’ ways of life?

As I wrote the final lines of this book, a violent earthquake in Mexico City sent me running terrified into the street, only to find out with relief that unlike the same date exactly 32 years ago – September 19, 1985– where more than 400 structures fell, this time, in 2017, only 40 buildings collapsed. That initial optimism faded as we learned of the disastrous effects in different parts of the country and the additional consequences caused by a previous earthquake that had struck just twelve days before; the strongest in one hundred years. In the capital, these earthquakes reminded its nearly 20 million inhabitants that the seemingly solid layer supporting thousands of buildings is technically still water and that seismic waves are magnified and accelerated in a ground of lacustrine origin.

The quakes of September 2017 revealed the distance between the reality of a place and the projects that pretend to impose themselves on that territory. They also exposed the effects of corruption in the construction industry: collapses were due primarily to irregularities such as that of a luxury residence built illegally over an elementary school where nearly thirty people died or housing structures clandestinely built over old houses. It soon became apparent that the earthquakes of September 2017 had been just as destructive as those of 1985 but in different ways. What were once small villages had become large cities lacking any urban planning or regulations. For example, Cuernavaca, until a few decades ago a paradise filled with weekend homes about an hour away from the capital, and Iztapalapa, an informal settlement on the outskirts established in the 1970s, each currently has two million inhabitants. The earthquakes were a reminder of the problems that everyone assumed had been resolved after 1985. The images of the destructions frightened a population that seemed impervious to fear. The contrasts between urban effervescence and rural abandonment revealed a country that does not know how to count its dead, protect its living, and safeguard its heritage.

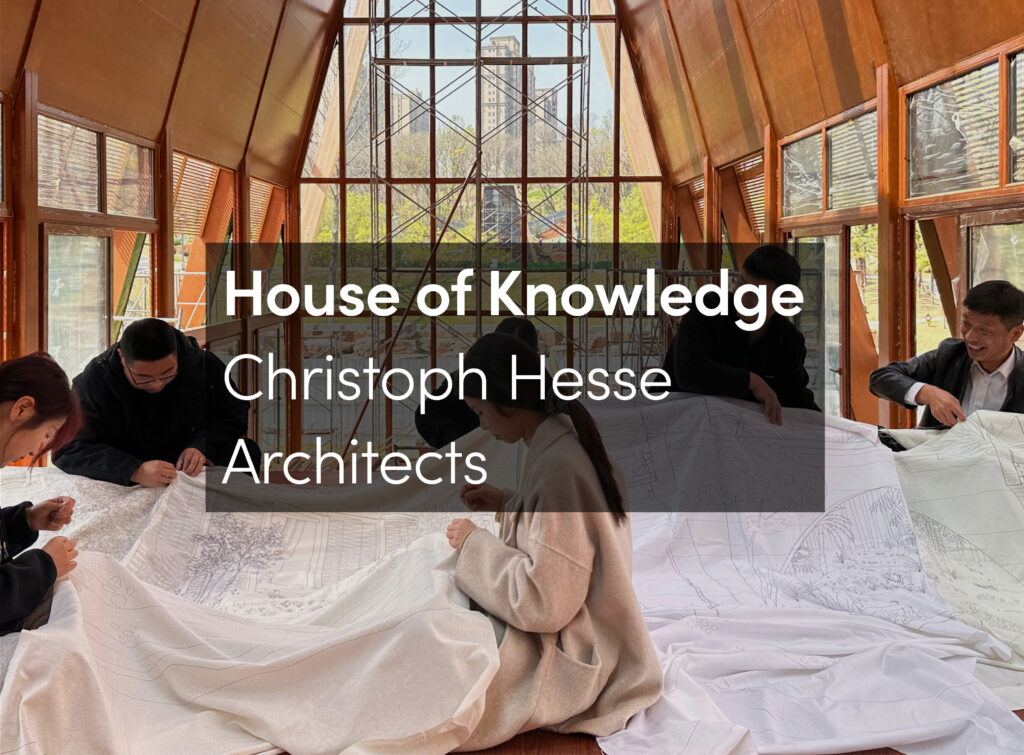

Building in the Navarte colony, 2017

Photography by Cuartoscuro

After the earthquakes, the government announced reconstructions that rebuff the importance of the existing legacy and are based on demolishing everything that stands in their way: replacing thousands of traditional homes with mass produced housing projects foreign to traditional ways of life, to the local climates, and to supporting infrastructure. This is a hasty building strategy that has forgotten what I attempt to address in this book: the importance of understanding the house as the space where personal histories are interwoven with the histories of a place and a culture. While governments are making one-sided, short-term decisions, as architects we are trying to organize interdisciplinary teams to address the difficult issue of providing housing for thousands of distant and anonymous users. The same themes tackled by John Habraken and Christopher Alexander decades ago have once again come to the fore around the world given the shortage of decent housing options in our increasingly inhospitable cities. This led me to re-examine the housing project that Alexander built in Mexicali in the 1970s. His book, The Production of Houses, about this project in northwest Mexico shows adaptable prototypes produced with the occupants; homes that relied on self-building and on materials produced on site by occupants…[1] In this book, all of the ideas that are always brought to bare in design are addressed here, yet, in today’s conditions, they seem unreachable. Alexander’s Mexicali project is not the large residential cluster suggested in the book but rather a small complex that currently houses a section of the Nursing School of the University of Baja California. It is also not a self-sufficient community or a new way of conceiving the city. It is just part of a city block buried among identical streets and houses that is inhabited by people who have never suspected that better housing designs could improve their lives.

Why have architectural contributions to cities been so small, when the benefits they offer to inhabitants seem so glaringly obvious? We continue building houses for a social structure that no longer exists and for abstract cities that differ greatly from reality. The rising number of natural disasters around the world is actually not caused by nature but rather by humans who have ignored the earth and climate’s natural behavior.

Among the thousands of photographs taken of buildings destroyed by the earthquakes that shook Mexico in September 2017, one seems particularly eloquent to me: it is an image of a housing block that is still standing but has lost part of the facade, revealing a series of fractured rooms almost hanging in mid-air. That image clearly reflects the private space: a half-made bed, dresses hanging in the closet, shoes set out for the next party, a blueprint tube leaning against the closet… From afar and through the camera lens, we are able to glimpse the most personal aspects of the occupants’ lives and understand their tastes, age, and many of their daily routines. There are no people in the picture and the damage caused by the collapsed facade is not visible. All we see is a frozen moment in the existence of a structure that seems as solid as it is fragile and quotidian as it is unbelievable. In the photograph of the damaged building, next to the rooms that have been left hanging over the abyss, other neighboring apartment windows appear to show a repetitive and anonymous façade. Unsurprisingly, that veiled façade shuts itself off to the city with distrust. That image clearly evokes the title of this book not only because it reveals the different layers of interconnected lives —above or beside each other, alone or crowded— that are present in the different housing, but also because it shows the responsibility of a few for the lives of many. We are dealing with structures that, whether we like it or not, we all share.

Mexico is an ideal place to find architectural examples that contrast scale, budgets, materials, and programs; a melting pot of transformations where the future of what is rural and urban are played out and where questions of identity, reconciliation, and survival are addressed. This legacy, sparsely documented and progressively illegible in today’s rapidly-changing cities, piqued in me the interest in gathering a compendium of architectural ideas and solutions that describe how some of the leading experts, in a specific country and over the last century, have sought to achieve a balance between individual aspirations and the need to create a common territory.

Given that most of the world’s houses have yet to be designed and will be the cornerstones on which our societies are constructed, this book posits new approaches to collective domestic typologies that make up the urban fabric. Its intention is to reactivate theories and drawings as elements that incite us to develop new ways of living. The aim is to bring together the connections between two concepts increasingly posited as polar opposites: the house and the city, in order to establish smoother transitions between the private space, the shared infrastructures, and the territory. For that reason, I have focused my work for more than two decades on building bridges between different periods, authors, and project scales, between two-dimensional graphic representation and three-dimensional space, and between the minimum housing unit and the urban space. This analysis is part of a broader work that I have developed (on the topic of housing): initially focused on low-income projects and later creating experimental prototypes and vertical housing projects and while continuously alternating between an architecture practice, teaching, and research agendas. The idea is to create tools capable of generating more open dynamics in an attempt to build less harmful environments.

Due to the privacy that a house provides, it is not easy to represent the ideals that have shaped our daily ways of dwelling. The aim of this book is precisely to provide that missing account: rethink the elements that define how we sleep, cook, construct our personal universe, and relate with others. Therefore, the book emerges from questioning the tools that we commonly use to design; the way we conceive and represent the house. The purpose is to gather the discourses of different authors in order to trace the meaning of privacy within shared structures; addressing the commitment of envisioning personal worlds for others.