A clinic in Kenya built by students in José Selgas’s MIT unit raises questions about the ethics of educational tourism in relation to the needs of the Global South Colonialism found in the Modernist project a powerful and willing partner for the shaping of conquered territories in the southern hemisphere. Today, amid a new wave of colonial activity based on subtler and less easily identifiable strategies, little is done to understand its effects on the way people live and give form to their shelters. Neo-colonialism is an urgent issue but one which most of the profession is ill-prepared to interrogate. In order to address the underlying questions of the appropriateness of architectural concepts and their technical implementation, local and foreign experience needs to come together in an unbiased way to negotiate the challenges of intercultural communication. This is an indispensable prerequisite if such cooperation is to have sustainable and productive results.

This loaded context defines the challenge in discussing the pavilion recently designed and built in northern Kenya, under the leadership of José Selgas and Ignacio Peydro, by a group of 10 MIT students. What tools does the current dominant architectural discourse possess in order to operate in conditions ‘so far from all the concepts and possibilities learned at MIT’, while at the same time engaging with cultural identities and societal needs of the builders-cum-occupiers? The pavilion’s elegant structure certainly raises questions about the significance of design studios focusing on the Global South (which seem to have become a ubiquitous component of studies within Western architecture schools), and also the difficulties of assessing the impact of such projects on local communities who ideally should be active participants in the process as well as being its beneficiaries.

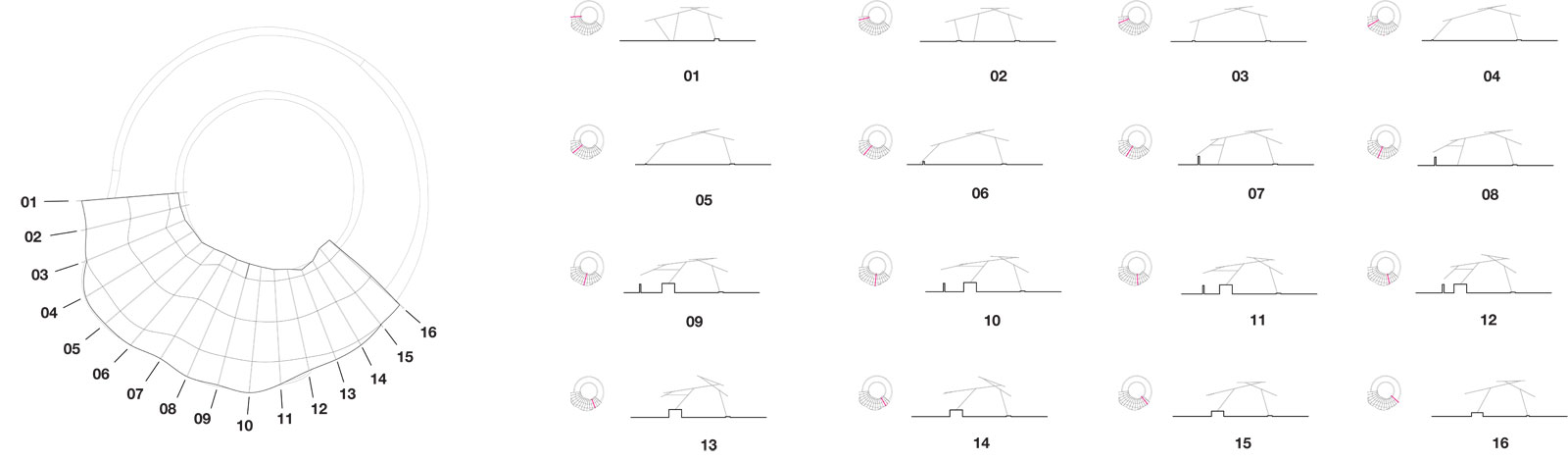

Site Plan

Access to good architecture, particularly for primary community needs such as health, nutrition and education, is a universal right. For too long this has not been the case, and a Western approach to charitable aid reduced results to ill-conceived, inadequate infrastructure builds quite literally in the middle of nowhere. Only on rare occasions are the failed projects accessible for scrutiny by a wider public. Last year’s Nordic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale focused on east African projects backed by Scandinavian development programs. The curators interestingly inverted an uncritical trend by displaying Karl Henrik Nostvik’s Fishery built in the late 1970s. In the same region as Selgas Cano’s pavilion, and supported by the Norwegian development agency, the fishery was never completed and was a ruin from the start. Whereas on the drawing board the scheme had appeared convincing, in reality it seems to have been doomed from its conception because it was not based on the demands and leadership of the community.

An extremely dry region in the north-west of Kenya, with only four days of torrential rain recorded each year, Turkana County is inhabited by a mostly nomadic and pastoral population of the same name. Widespread malnutrition is one of the issues that the Missionary Community of Saint Paul the Apostle (MCSPA), based in the region for more than 20 years, has been trying to mitigate. The NGO dedicates particular attention to women and children, the most vulnerable people in a patriarchal society such as the Turkana. MCSPA runs a vaccination and education clinic, responding to a real needs expressed by the community, but its existing small building was inadequate for this purpose and did not offer any protection for visitors in the waiting area.

The challenge of the aptly titled ‘UNMaterial’ design studio at MIT was eloquently described by Selgas as ‘exploring the possibilities of working with less, even nothing in the middle of nowhere’. The goal was to develop his students’ skills in employing common materials in innovative ways, and to obtain the maximum with the minimum by creatively reacting to a specific material (or even the lack of material). To facilitate a better understanding of the theme and the location for all participants, students were encouraged not to use computer, or any other digital technique. Each student designed in plans, section and models, which were eventually synthesized resulting in the final design − a skeleton of scaffolding poles, ingeniously assembled by the repurposing of scaffolding clamps, in a sinuous circular shape that finds its precise positioning among four existing acacia trees on the site.

The proliferation of the Western quest for exotic adventures has led to a new form of educational colonialism

During the semester a full-scale prototype was built in a week by three students, and later, in July 2014, two groups travelled to Kenya to assemble the entire structure. The first group laid the groundwork, prepared the site, cast the reinforced-concrete foundation plinths, and trained local workers, while the second assembled the scaffolding structure, walls and roof.

Plans

Diagrams

In plan the scheme reads as two concentric enclosures. One low circular stone wall embraces three of the trees that cast shadow on the interior space, whereas the shape of the exterior circular wall is determined by the decision to incorporate the fourth tree. In the torus-like surface created between the two walls, shadow is cast by a portico roof resting on the scaffolding, which provides a sheltered space for community meetings and the educational and nutritional program. Metal sheeting or thatched roofs were considered, with the former chosen for the final construction. Under the roof, a small drop-shaped wall made of cast-on-site cement blocks houses the consultation and vaccination room.

It is an intelligent and aesthetically quite exquisite piece that raises various questions. The pavilion at first appears as an overtly ‘primitive architecture’, reinterpreted through the eyes of a skilled practitioner and teacher like José Selgas and his students, but there is an underlying affinity between the idea of operating with a ‘kit of parts which integrate forms and methods of vernacular Turkana architecture’ and the way Richard Sennett’s The Craftsman advocates the importance of practical work for human beings. Sennett argues ‘that people can learn about themselves through the things they make, that material culture matters’. However, although evoking nomadic shelters, using material found on site as supporting structure, and covering it with scrap, seems a good strategy vis-à-vis the traditions of the local community, it is difficult to uncover the extent to which the project did indeed inform students not only about technical or economical necessities, but also about the social, political, cultural and environmental context of their work.

Given the aesthetic appeal of the project and Iwan Baan’s seductive images, it is not easy to shift our focus from the product to the process. However, this is necessary. As Hans Skotte, a Norwegian professor who has long dedicated his energies to architectural education and practice in East Africa, puts it: the ‘real-life success or failure [of a project] is for the people to judge. We can merely assess the architecture of the process’. In the case of Turkana, this process ultimately appears to be a mostly Cambridge, Massachusetts, driven one. It’s not unreasonable to hope that the next African scheme to be published in an international journal, or trending on social media, will be based on the efforts of an African school of architecture.

As a showcase project, the Turkana Pavilion obviously amplifies the credentials of MIT in training students to ‘work with scarcity’. This is particularly important in the United States, where currently almost 30 schools offer learning-by-doing programs linking experiential education with social agendas and technological innovation. One of the most famous of these programs, Rural Studio at Alabama’s Auburn University, established in 1992 by Samuel Mockbee, explicitly aims to explore ‘how architectural practice might be challenged with a deeper democratic purpose of inclusion’.

At Kokuselei, however, ‘inclusion’ is particularly hard to uncover. A cursory glimpse at the studio costs reveals that the overall expenses for the MIT team’s travel and accommodation, around US$20,000, represent over one third of the overall budget. In the long run these price tags should lead to a reconsideration of the ethics of foreign-led design/build projects in so-called ‘developing’ countries. The proliferation of the Western quest for exotic adventures has led to a new form of educational colonialism, where it is extremely hard to see how the important material means employed by foreign agents contributes to redress growing global inequality, or at the very least improve local capacities and skills.

Ultimately, however, it seems that those who stand to make the most out of this extraordinary experience are foreign students: a point proven by the fact that, during construction, the MIT team ‘had to change the material because on site [they] realized that to do the masonry work was too complex for the people there, [who are] completely unskilled’. If the completed facility of concrete blocks looks like it will last, its role as an agent of change for the Turkana population is rather less evident.