From engaging to empowering people: a set of co-design experiments with a service design perspective [1].

1.1 Collaborative Services and the City

In recent years cities have been undergoing a profound transformation, characterized by a new wave of activism on the part of their citizens, who are seeking to improve the quality of their urban life and determine the identity of the spaces they live in.

Cities are now sites of resistance and contestation (Short, 2006), but at the same time they are places of experimentation, where people are starting to innovate what is already there without waiting for the arrival of a bigger, top-down change. This is why citizens are the protagonists of a new innovation age that is witnessing the birth of Creative Communities: “people who cooperatively invent, enhance and manage innovative solutions for new ways of living” (Meroni, 2007, p.30).

Many of these solutions deal with designing services, because it is especially within cities that the growth of the service sector is evident: cities are places where it is necessary to provide and benefit from services, where mature economies have rapidly shifted from manufacturing to service-based economies (Kim & Short, 2008).

Confronted with a lack of services inside a city, what is now happening is that local communities are seeking to solve the problem from the bottom up, in unprecedented ways, generating original cases of social innovation.

The relationship between services, social innovation and the city is at once both a simple and a complex one: Creative Communities are an original outcome of cities because they are born and develop more quickly in contexts characterized by diffused knowledge, a high level of connectivity, and a certain degree of tolerance towards non-conventional ways of living (Manzini & Jégou, 2008). They have found less costly solutions to their needs through new forms of sharing and self-production, originating a new generation of services, known as Collaborative Services. These are “services where the end-users are actively involved and assume the role of service co-designers and co-producers” (Manzini & Jégou, 2008, p.32). The end-users are the same citizens who are participating in the new wave of urban activism. They are real “service thinkers and makers” (Selloni, 2013) who are contributing to building systems of sustainable development, or, as Manzini and Jégou (2003) suggest, a body of products, services and knowledge that enable us to live better together, consuming less and regenerating the quality of the contexts in which they are used.

Collaborative services have taken a less pioneering shape in recent years as part of the collaborative consumption that Botsman and Rogers (2011) have described as traditional sharing, bartering, lending, trading, renting, gifting and swapping redefined by new technologies and peer communities.

All these elements contribute to shaping a form of social innovation in which citizens become designers of their daily lives, co-designing services and developing them using existing assets and resources.

As service designers and researchers in the field of design for social innovation, we are especially interested in investigating how this process could be enhanced, what kind of intervention format could foster it and what the role of the professional designer is within these dynamics in order that an initially informal initiative may develop into a real service, eventually to be scaled-up. This also implies using design methods and tools to explore the shift from engaging to empowering people.

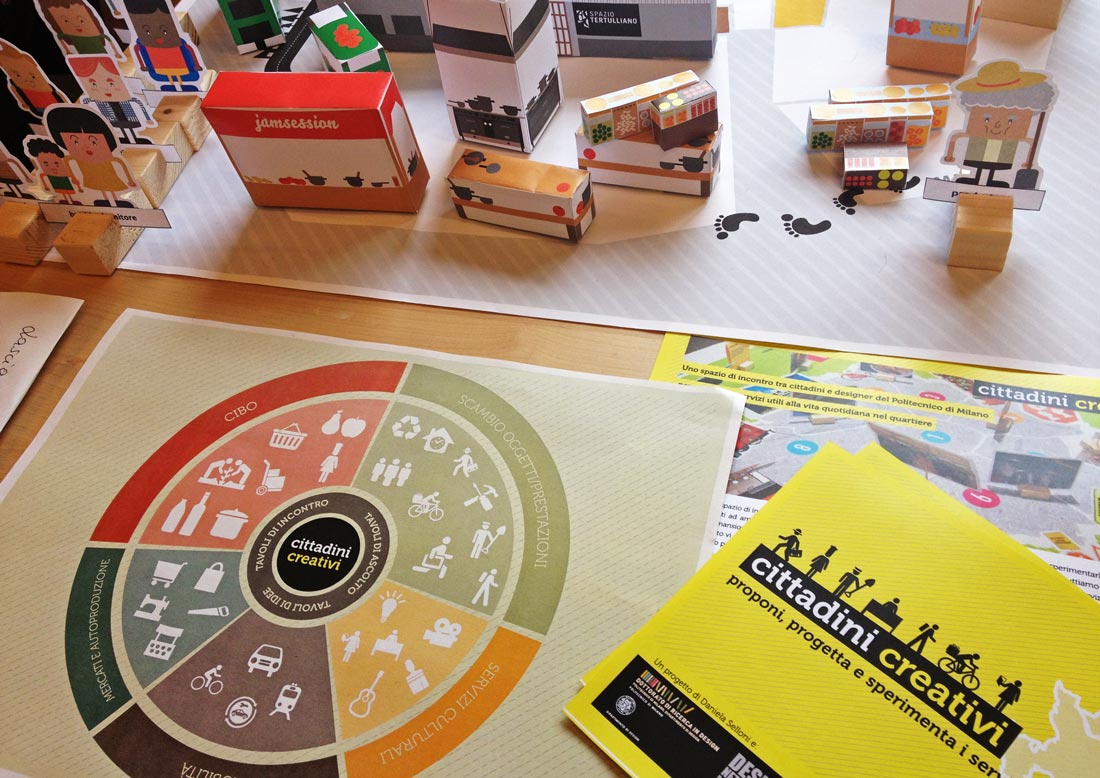

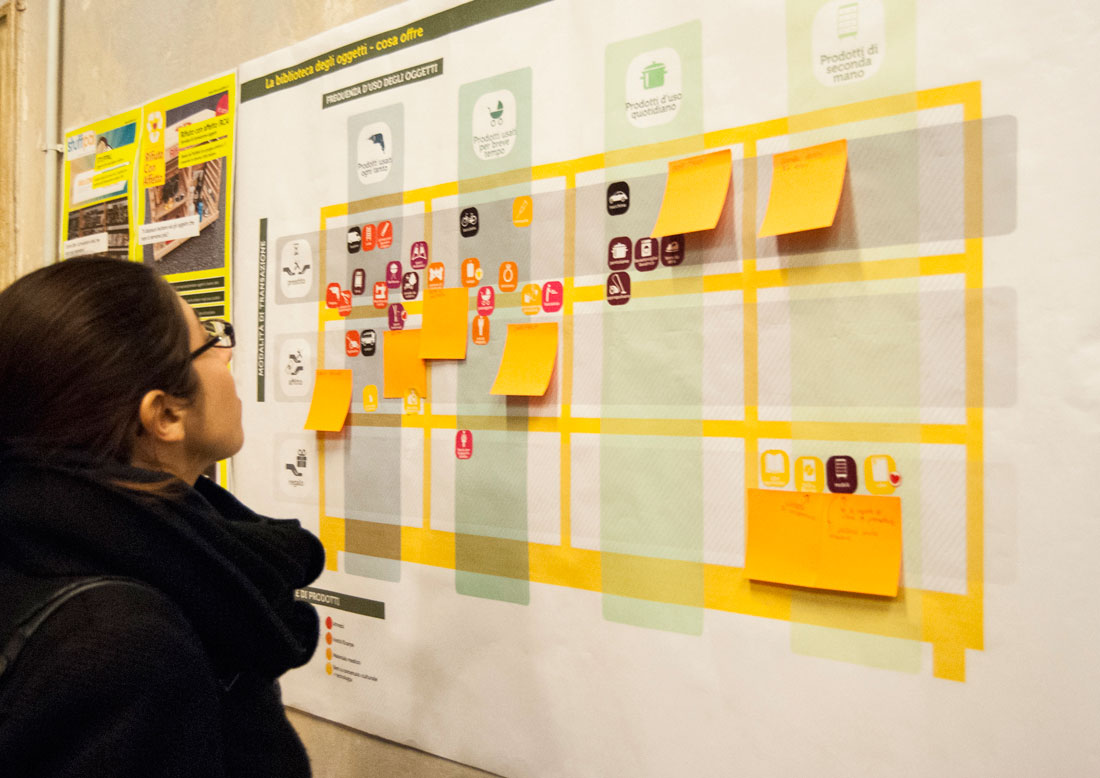

Creative Citizens during a co-design session

1.2 Participatory Design, Community Centred Design and Co-design

Co-design, co-creation and co-production are buzzwords that refer to the inclusion of users and producers of products and services in their creation. Even though some distinctions have been made (e.g. Sanders, Stappers, 2008) in an attempt to give them different connotations, they are generally defined as broad terms potentially covering activities carried out at different stages of the project development and involving people with various degree of participation.

From a service design perspective we look at these collaborative activities framed into a process that moves from the definition of a service idea – the concept, continues with its implementation together with the stakeholders, and concludes with the service ready to be used. In order to develop this process, the methodology we adopt in our research activities pertains to articipatory Design (PD) as defined by the Scandinavian school (Ehn, 2008; Bjögvinsson, Ehn & Hillgren 2010; Emilson, Serravalli & Hillgren 2011). The authors look at PD as a movement “from designing “things” (objects) to designing Things (socio-material assemblies)” and they argue that “this movement involves not only the challenges of engaging stakeholders as designers in the design process, as in “traditional” Participatory Design (i.e., envisioning “use before actual use,” for example, through prototyping), but also the challenges of designing beyond the specific project and toward future stakeholders as designers (in other words, supporting ways to “design after design”, i.e. after the conclusion of the design process for the specific project). And they see this movement “as one from “projecting” to one of “infrastructuring” design activities” (Bjögvinsson, Ehn & Hillgren 2012, p.102).

This means that the work of professional designers in this process ranges from engaging nonprofessional designers in envisioning and co-designing future service ideas, to involving potential stakeholders in the process, aligning their interests and empowering them to create self-sustainable services after the end of the design project.

In this framework, co-design is meant as just one of the strategies adopted to increase effectiveness in supporting social innovation. In fact others are used in parallel, such as some forms of ethnographic research and observation in the first stages and alignment of the interest of different stakeholders, depending on the opportunities emerging during the service implementation.

When designers work with a well defined group of people behaving as a community, with common values and a shared vision, PD assumes a specific connotation strictly linked to social innovation: in our research activities we call this methodology Community Centred Design (CCD).

Looking at the work of our research group, Polimi DESIS Lab, design for social innovation is mainly carried out within this framework.

Meroni refers to design focusing on creative communities as CCD, “where understanding values and behaviours and collaborating with the most active social communities in conceiving and developing solutions […] is the distinctive work of the designer” (Manzini & Meroni, 2012).

This approach moves from looking at social innovation as a driver towards solving emerging social issues, and at creative communities and collaborative organizations as prototypes of new and sustainable ways of living. These ‘prototypes’ could be scaled-up and become models for new behaviours in a sustainable society. CCD is the approach guiding design actions to support these groups of people.

CCD does not focus on the user (user-centred design) but on the community as the enabler of local change, as a resource to be valorised and from which to learn. In this perspective two main competences are required from the designer working with this approach: on one hand, the ability to gain knowledge about the community by field immersion and the development of an empathetic relation with the people; on the other hand, ability to use design knowledge to design with and for the community, developing specific tools to enable them to co-design solutions to their own needs.

In this paper we focus especially on co-design activities as a peculiar work of designers and researchers working for social innovation. We call them “experiments” for their experimental nature and uncertain results. In fact the aim of the research activities described in the following paragraphs is to understand how service design can foster social innovation by developing a set of participatory and community centred activities in a defined context. More specifically what we are investigating in our research is how a set of co-design experiments could foster the growth of a new generation of services enhancing social innovation.

Creative Citizens during a co-design session