Ethiopian Affordable Housing Program was created as a response to the enormous challenge of housing in the country. Initially the program set an ambitious target of constructing 400,000 standardized and affordable condominium units, creating 200,000 jobs and supplying 6000 hectares of serviced land per annum between 2006 and 2010. While at the beginning, pressed by time and growing population, the main task was mainly quantitative, and required the State’s tighter hold of reigns over the entirety of the process, in order to produce as many units as possible, at this point the position is more relaxed. This situation where more than half of the planned units have been built allows us to reflect upon the Housing Program, with its benefits and upsides and also to examine alternatives and look for improvements to its stages and factors. Careful dissection of the process enabled us to detect possible new actors and directions in Ethiopia’s Affordable Housing Program. This paper analyses the achievements of this remarkable housing program and also suggests some positive directions for the future.

Introduction

The Ethiopian Integrated Housing Development Program is a unique and bold departure from the cautious and incremental approach that has dominated the rhetoric and practice of development in the cities and regions of third world countries. In the decades immediately following the political independence most third world nations took steps to provide housing for the poorest and most deprived sections of their population. During the 1960s and 1970s the strategies to tackle the immense problem of housing shortage focussed on the strategies of involuntary resettlement and direct housing provision by the government. The state was seen as the main actor capable of meeting the housing challenge.

As the years went by, the faith in the strategies of public housing provision declined rapidly. The centralized and bureaucratic systems of governments in most third world countries simply could not keep up with the sheer speed and scale of the problem. The populations of the major cities in Asia, Africa and Latin America exploded with a majority of the urban population forced to live in slums and informal settlements on marginal parcels of land. The bureaucratic state machinery could neither provide developed land at an affordable price in sufficient quantity nor construct affordable housing units in substantial numbers within a short time. The result was a proliferation of slums.

Even in those situations where affordable housing units were provided they failed to serve the overall purpose for two major reasons. One, the multistories tenements constructed by the government did not achieve substantially higher densities than the inner city slums that they intended to replace. Second, the multi-storied structures limited the livelihood choices of the poor who preferred single storey dwelling units to be able to run small shops and businesses from their homes. Moreover, the involuntary resettlement of slum populations destroyed their livelihood linkages with the city proper and further plunged them into poverty.

From the 1970s and 1980s onwards the strategies for meeting the housing challenge started shifting away from direct provision. This was the time when the concept of participation started gaining prominence in developing theory and practice. There was a major rethinking of the role of the state in housing provision. The trend shifted from strategies of provision to strategies of enablement, where the state would be just one of the many actors involved in solving the housing problem. The focus was on slum upgradation and not housing provision. It was considered wiser to provide relevant social and physical infrastructure such as paved streets, water supply, sanitation, street lighting, schools, medical facilities etc. rather than construct individual homes. Furthermore, these upgradation processes were to be planned and implemented with the active participation of the residents at every stage. Participation of the resident community would decrease the occurrences of conflicts, make the planning process effective and give the people an increased sense of ownership.

Research and practice also showed that if informal settlements were granted security of tenure then the residents tend to invest their savings in improving the living conditions in their settlement. It is obvious that the poor would never spend their meagre savings on a settlement which could be demolished by government authorities at a day’s notice.

By the end of the 1980s, the governments of most third world nations, the non-governmental organizations working with the urban poor and major development agencies had shifted over from housing construction and provision to slum upgradation using participatory means.

The futility of housing provision as a strategy was further confirmed when planning authorities of developed nations started demolishing the affordable housing blocks they had developed during the 1950s and 1960s. In most cities in Europe and North America, these initially vibrant affordable housing projects had turned into derelict areas shunned by the residents themselves, and hubs of crime and social destitution.

By the turn of the twenty-first century direct housing provision was not even discussed as a possible solution to the housing problem. The only reason they got mentioned at all was to reiterate their utter uselessness and guaranteed failure.

It was exactly at this time that the Republic of Ethiopia decided to turn the history of affordable housing on its head by embarking on a program that was based entirely on state supported housing construction and provision.

The Integrated Housing Development Program – A Unique Reversal

In the year 2005 initiated the Integrated Housing Development Program (IHDP), with the ambitious goal of creating 360000 affordable housing units in the first five years of its implementation (2006-2010). Popularly known as Condominium Housing, due to the type of housing units constructed, the program involved the creation of multiple storied condominium units wholly financed and supplied by the Government.

As discussed above, this whole approach was a complete reversal of the developments in the theory and practice of affordable housing. In its study of the first five years of the Program the UN-Habitat stated that, ‘Ethiopia is one of the few countries in Africa that has implemented a program at such an ambitious scale. The large scale contrasts the prevailing approach of small-scale project-based slum upgrading and housing cooperative schemes.’ (UN-Habitat: 2011).

However, it was argued by the Ethiopian authorities that the shortage of quality housing stock in Addis Ababa was so high that any kind of bottom-up, incremental and upgradation based approach would just not have the necessary results. Even as per the UN-Habitat and other independent researchers, more than 80 per cent of the population in Addis Ababa lived in slums (UN-Habitat: 2011, Davis: 2007). Although the primary aim of the Program was to address the housing problems in the city of Addis Ababa, a substantial number of condominium units were also made in the cities of the different regions by the Regional housing authorities and boards.

Although the targeted number of units could not be created the Program was still a massive success. Demand for the units was extremely high and continues to be so, not just in Addis Ababa but also in the regions. As the emphasis was always on supplying the largest number of well-constructed units in the shortest possible time, many subtle aspects of aesthetics, interiors and open space design had to be undermined. The architects and designers often lamented the uniform look of all the units and housing sites and the lack of variety and aesthetics, but so far these shortages have not affected the high demand for the units.

A massive housing stock has been created catering to the needs of middle and low income families and many of those families have become landlords who rent out their units to other low income families. According the UN-Habitat study there were three main achievements of the Program which were largely unexpected –

i) The high demand and support for the program

ii) The creation of many low-income landlords

iii) Positive changes to the rental housing market

Construction, Constriction and Stigma

The authors of this paper argue that there some other unexpected ways in which the IHDP surprises the opponents of government led affordable housing programs. Professor Lawrence Vale of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and an expert in the field of affordable housing wrote that one of the main problems with public housing in the United States was that they were communities which were both “constructed” and “constricted” that the identities of public housing projects and their residents are almost always “proposed” to them and “constructed” by outsiders such as architects, planners and the staffs of housing authorities (Vale: 2002, p – 11).

He referred to sociologist Gerald Suttles who wrote, ‘Neighbourhoods seem to acquire their identity through an on-going commentary between themselves and outsiders. This commentary includes the imputations and allegations of adjacent residential groups as well as coverage given by the mass media. It includes also the claims of the boosters, of developers, of realtors, and of city officials.’ (ibid).

In the initial years of these projects this was not so much of a problem. Vale writes that in the early years most of these projects were vibrant ‘bastions of social capital’ (ibid). But as the middle class families started moving out of the projects to better housing options the living environment of these projects started declining. Just like in Ethiopia, these projects were designed as single-use residential enclaves, which got progressively isolated and alienated from the city proper. Vale concluded that in this sense, these projects could be called both “constructed” and “constricted” (ibid).

The housing units and projects created under the IHDP are also wholly “constructed” but they are absolutely not “constricted”, at least not as yet. It is “constructed” but not in in isolation. It is part of a vast program of nation building – physically, economically and ideologically. It is together with the Millennium dam, the Addis Ababa city-rail project, the inter-city highway construction projects and so on. Apart from being affordable housing, it is also a symbol of a new Ethiopia which is determined to erase the stigma of under-development, famine and war. Peace, stability and economic progress at any cost.

The other issue that plagues public housing projects all over the world is the issue of stigma. There is no stigma attached with being the resident of an affordable housing project in Ethiopia. The general image of condominium housing to the “outsider” is not of failure, but of success. The “outsiders” want to be and often do become the “insiders”.

Reflections and New Directions

Having accounted the positive aspects of the IHDP the authors of the paper now wish to direct the attention to the aspects which could become major problems for the program in the decades to come. It must be kept in mind that although the IHDP does not suffer from many of the issues that led to the failure of public housing projects in other parts of the world, processes of economic and social transformations in Ethiopia may well create those issues in the future. With increase in public-private-partnerships and economic growth, the private real estate development sector will grow. Rising incomes of the middle classes, a bigger role played by private developers and diminishing role of the state may prompt the middle classes to move out of condominium projects and seek other options. Though this scenario is a far cry from the current political-economic situation, the possibility is nonetheless there.

In a study conducted by the authors in condominium housing projects in Mekelle, most of the residents of single-bedroom units expressed a wish to live in a single-storied plotted villa is they had the possibility. They consider the condominium unit to be far better than the housing they had earlier but it lies somewhere between what they had and what they wish to have. The perception of quality affordable housing differs considerably depending on who is doing the perceiving. To the architects and designers, the uniform condominium projects are a blot on the urban landscape but so are the plotted villas of the prosperous which are often a caricature of villas in developed countries. The housing authorities often like to see quality purely through the lens of quantity. But to the residents of these projects, the image quality housing goes hand in hand with their image of what symbolizes economic and social poverty or prosperity in the urban environment that they are familiar with. A villa which may seem to be a caricature to a designer might be the lifelong dream of a poor family. In such a situation it would be impossible to retain the residents in the projects if their income rises and the market responds by providing more housing alternatives.

Reflections on Primary Strategy

The first reflection the authors have is regarding the primary strategy of the IHDP. So far the strategy has been state led, state financed and focused on the creation of standardised and primarily single-use residential projects. The authors believe that in the future this strategy should be enhanced to include the strategy of inclusionary housing. According to Patel, ‘inclusionary housing refers to a set of programs and policies which make it mandatory for a private developer to provide social or affordable housing as a condition for the permission given to him to carry out his development.’ (Patel: 2011, p – 13). In other third world countries such as India inclusionary housing has become one of the accepted and practiced methods of affordable housing provision. The developer gains in the form of state assistance to access land in prime locations and, in return, must construct a certain minimum number of affordable units. In the city of Kolkata in India the private developer has to construct 50 per cent of the total units or a certain percentage of the total allowed floor area as per floor area ratio (FAR) specifications (whichever is higher) for the middle- and low-income families.

The cost incurred for the construction of affordable units would get cross-subsidised by the sale of the units for high-income families and commercial properties. This strategy is in line with the increasing realisation among the private developers of the profitability of mixed-use projects. The strategy automatically ensures a certain amount of social inclusion as the units of the different income groups would be clustered in the same parcel of land. The mixed-use nature of the projects ensures economic opportunities for the different income groups. Most importantly, the low income groups don’t get pushed out to the peripheral margins of the city, which are the only locations where land values would be low enough for constructing single-use affordable housing projects.

In Ethiopia, a variant of this strategy could be created by creating greater institutional connection between the affordable housing authorities, which are responsible for constructing condominium projects, and the local governments, which are responsible for overall planning and management in the cities.

Reflections on Design, Decentralisation and Context Sensitivity

It is easy to understand the adoption of standardised and homogenous designs for the condominium housing projects in Addis Ababa considering the pressures on land, sheer scale of the need, limitation of time and high land values. However, when the condominium projects were constructed in the cities and towns of the different regions, exactly the same designs were exported to these places irrespective of the varied nature of the need, cultural habits and climatic situations.

A city like Mekelle has very different realities when it comes to availability of land, profile of beneficiaries, total number of units required and environmental conditions from Addis Ababa. But there is absolutely no difference in the types of units built. Although the demand for condominium units is very high in the regional cities and there is no occurrence of unoccupied units, such a strategy of uniform design is contrary to the philosophy of decentralisation.

The regional housing authorities do not have to deal with the extreme pressures that are prevalent in Addis Ababa. They should, therefore, be allowed and encouraged to develop context sensitive designs and layouts. The Indian experience with inclusionary housing shows that it helps to make the designs of affordable housing more aesthetic and context sensitive too. The developers like to use good architects to increase the marketability of their projects. When they are obliged to develop affordable units the high-quality architectural inputs flow into the design of these units too. In Ethiopia one can explore the possibilities of forming new partnerships involving the regional housing authorities, emerging private developers and micro-enterprises. Such a process will strengthen the process of political and economic decentralization too.

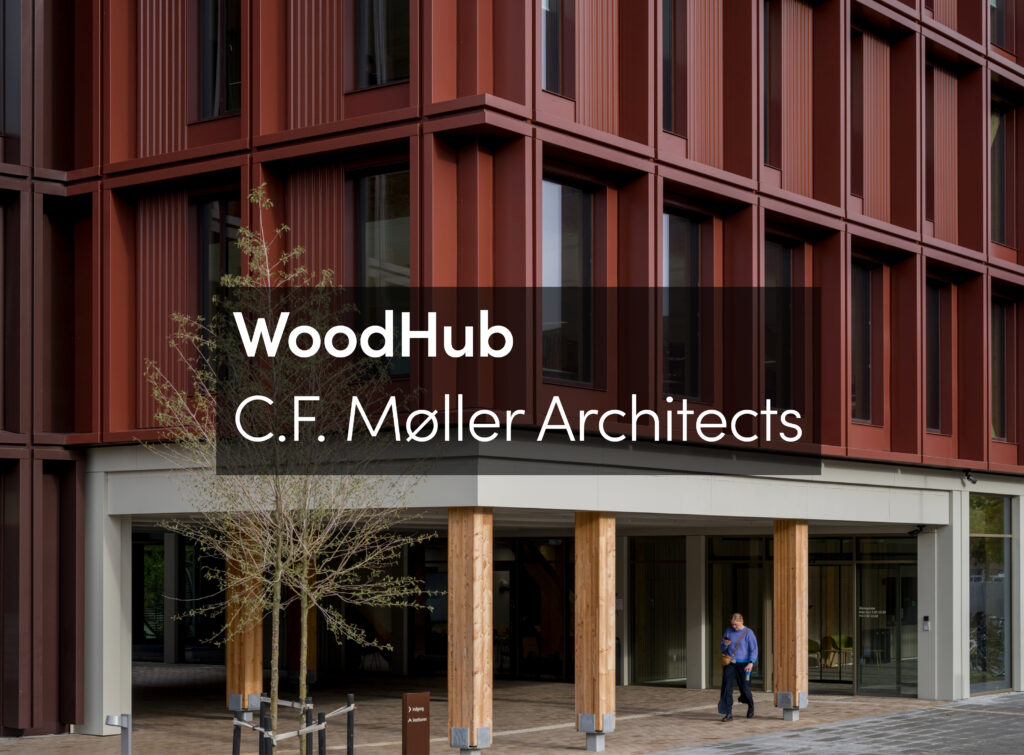

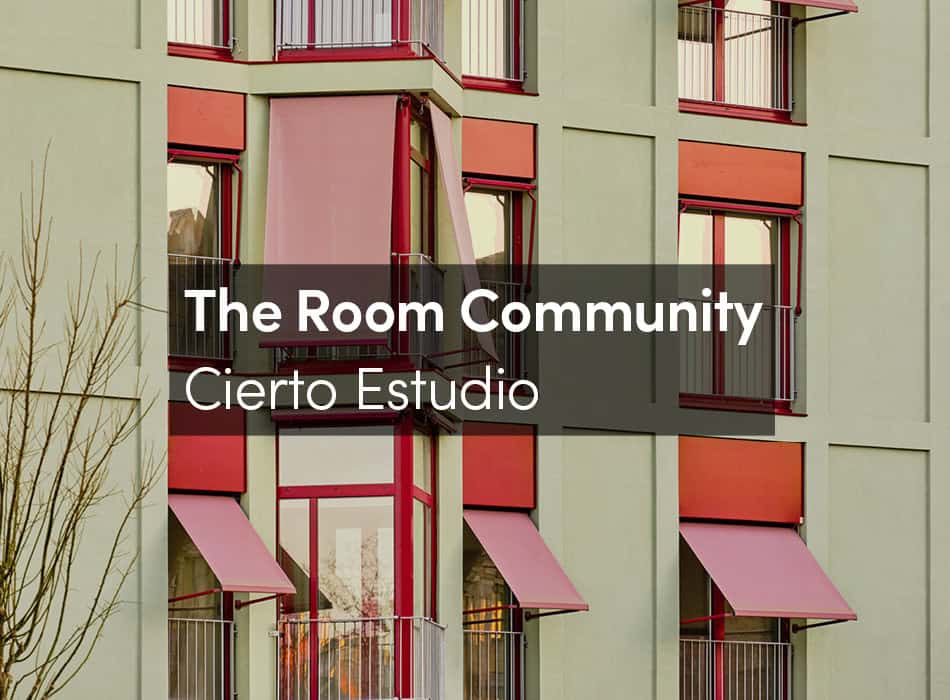

Regarding the quality of final product, a good practice has been introduced by the Ethiopian Association of Architects, for major competitions, where a local architectural company needs to pair up with a foreign firm, with proven expertise in the field similar to the design task at hand. In the cooperation, the Ethiopian firm acts as project leader, but the international partner helps to overcome the inexperience in design of unfamiliar typologies. Similar practices might be applied to the new affordable housing projects.

Reflections on the Role of the Academia and Participatory Design

Involving the local academic community and pairing them with government institutions or private construction and developer companies might lead to development of production of local, Ethiopian context-sensitive materials and implementation of appropriate design processes, which would give equal importance to both construction speed and quality.

Research of such issues is already being conducted at country’s top universities. However, the linkage in that regard, between universities and government institutions is very weak, so its findings never get delivered and implemented into reality. A possible solution, introduction of specialized research centres, which would serve the purpose of conducting research for both private companies and government bodies, has been mentioned by some academic experts.

The study of condominium projects in Mekelle done by the authors has shown interesting practices of resident’s use of them as well as many architectural shortcomings. Such mistakes forced residents to be creative: Lack of common spaces where communal activities can be performed and which are essential to Ethiopian “way of living”, made residents perform these activities on balconies and stairways.

Poor or non-existent landscape design around condominiums, which made the building surroundings useless, instead of being vibrant places of gathering for residents, made the cultural transition from low-rise courtyard tip homes to medium-rise one, very hard for people.

Such examples prompt introduction of participatory design in the housing program, with future residents either being involved in the initial stages of preparing design layouts, or if that is impossible due to deadlines, scope of projects, or the fact that the final user is unknown, then at least making apartment layouts flexible enough to allow some changes to be made after the residents move in. Participatory design elevates people from the position of passive buyers and users, to ones who share power over deciding how their living surroundings look like. Such empowerment is not without its dangers, as it can slow the process, make it less sustainable and more prompt to errors, so it should not be introduced hastily, but rather learnt from numerous, well-developed foreign examples and then adapted to local conditions.

Post-occupancy studies done by government offices have been very rare in the affordable housing program of Ethiopia. It is crucial that such mistakes are noticed and studied, in order to avoid them in future. This could be done only by universities, as they both possess the knowledge of conducting research and are impartial to the entire process. Assistance of foreign universities in such projects is vital, as they possess the knowledge and experience derived from their own housing programs. At the same time they are stripped of financial interest in the program, since a very common problem with assistance of foreign companies is that their help is sometimes linked with their future financial benefit

Conclusions

The paper shows that the Ethiopian Integrated Housing Development Program has been a unique exercise in the history of affordable housing as it challenged and reversed the prevalent emphasis on small-scale, incremental and upgradation based strategies. It was also seen that the Ethiopian experiment was not wrong in its assumptions as the program created a huge stock of housing for the middle and low income groups, improved the quality of the housing stock and was an economic success due to the extremely high demand for the housing created.

However, despite all the achievements, the paper has also shown some of the potential risks that the program faces and the shortcomings that it suffers from, all of which emanate from an over-centralization of the process of planning and implementation. The aim of the paper is to enhance the benefits of this remarkable program while addressing its risks and shortcomings. The reflections and new directions elaborated in the paper hope to contribute to such a process of constructive critique.