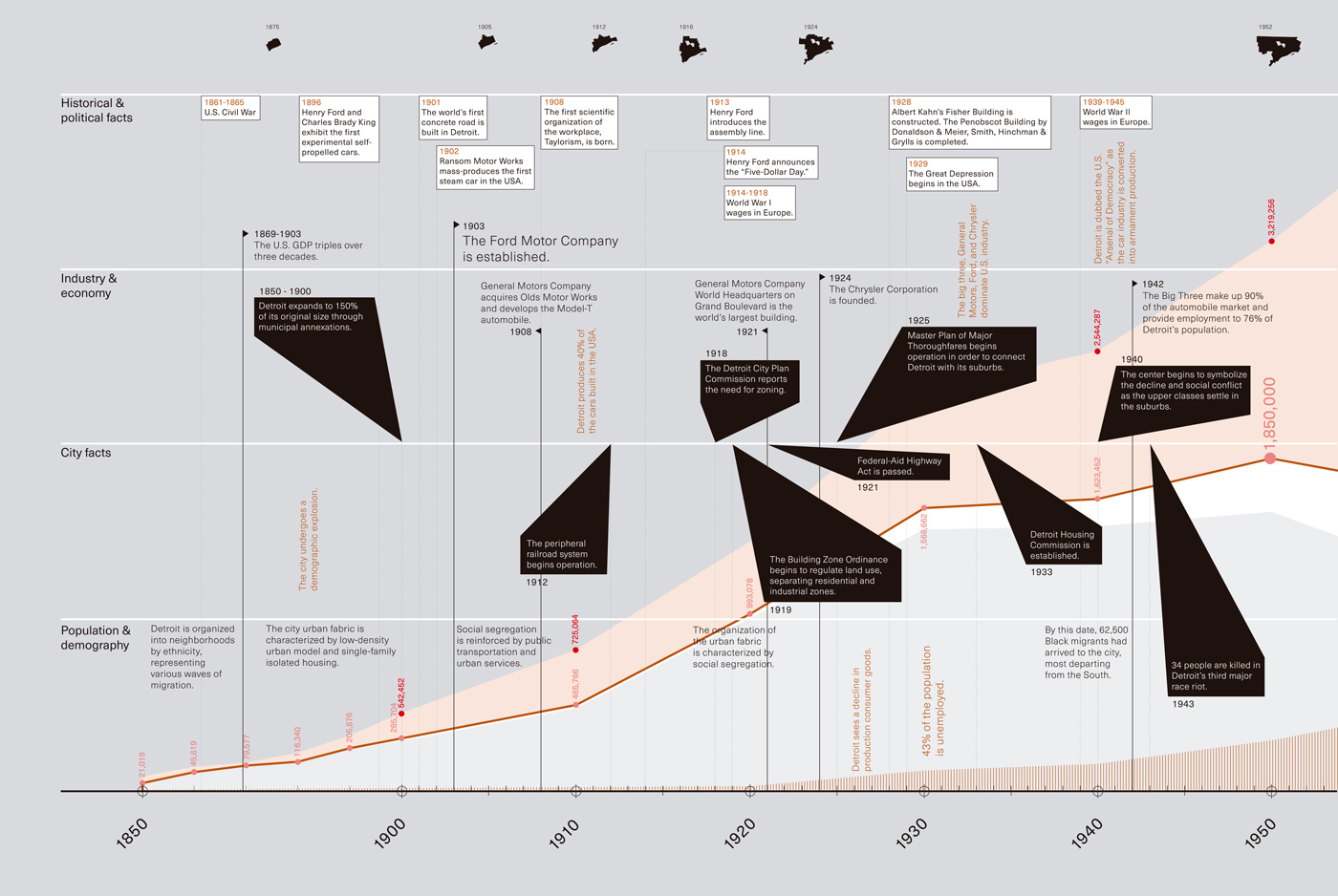

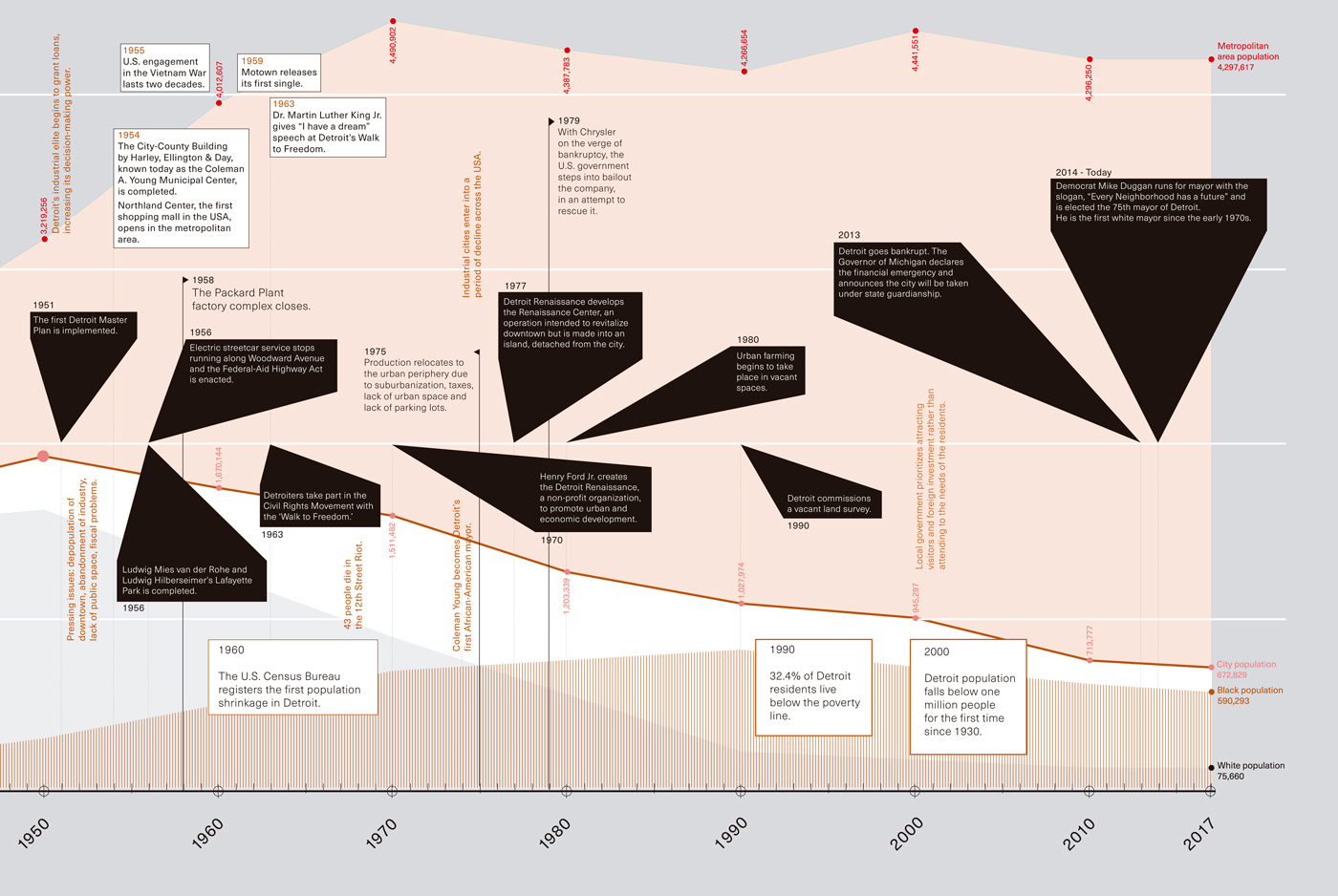

In his curatorial text for the Shrinking Cities[1] conference in 2004, Kyong Park used Detroit as the main case study for the phenomenon, and concluded with one open question: do shrinking cities grant greater power to global capitalism, or are they the places where post-capitalist economic models will form?

Fourteen years later, the picture has become even more complex; and still is quite blurry. The emergence of the sharing economies, as well as other alternative models, have impacted our societies to the point that we need to rethink and redefine all of our terminology. The global political landscape that has taken shape over the last few years offers another reaction to these changes. We are witnessing how conservativism, extremism, and various forms of fanaticism flourish in times of uncertainty.

Detroit represents the climax and decay of a global project that was encapsulated in the American Dream—of progress related to a heroic industrialization, of welfare related to consumerism, of economic growth related to urban sprawl, of social integration. The Motor City’s streets lewdly show the physical trials and scars of the 20th century, that seem to be claiming to be re-signified. The city that was once the cradle of Fordism and experiments in production found itself ahead of the curve in another kind of process in which there was a shrinking timetable of change. It all happened so rapidly that the demand for adaptation was overwhelming for everybody and everything.

Today we face the peculiar results of those urban processes; here, a recession is not the same as a reversal, as returning back in time. Decentralization, dispersion and communication have supplanted infrastructure, a densifying fabric, and physical exchange of capital. Since Google replaced Ford, the rural and the urban are no longer opposites. Detroit’s coexistent singularity and commonality have inspired new ways of thinking about the contemporary city and its problematics—Charles Waldheim’s concept of Landscape Urbanism[2] was, for instance, inspired by these processes. Over the last few decades, this critical territory and its social complexity have also required the testing of new models and fostered needed innovations, startups, and entrepreneurship. There is no clear map for ideal progress, there is no certain light at the end of the tunnel.

Planning History of Detroit

1. DETROIT FORTIFICATION & AGRICULTURAL FABRIC

By 1730, Detroit developed its agriculture along the riverfront. The “ribbon farm” lots are long and narrow so that each could have access to the water. Several of the “ribbon farm” owners gave their names to the actual streets. The topology of the “Fort Pontchartrain du Detroit, 1764” drew the principal avenues of the actual Detroit.

2. AUGUSTUS B. WOODWARD PLAN & “TEN TOUSAND ACRE GRID”

After the Great Fire of 1805, the governor decided to call Territorial Judge Augustus B. Woodward to develop a new urban fabric. In 1818, the plan was abandoned and only a fragment was used, that section is today’s Downtown Detroit.

3. DETROIT IN 1825

4. JEFFERSON GRID WITH THE PRINCIPAL AVENUES

The Jefferson Grid, developed by the U.S. Public Land Survey System, is a grid system used to implement propriety. It determines the orientation of the future of the urban fabric.

5. HIGH WAY AND RAIL SYSTEM

The railroad system is an antecedent of the grid that led to contemporary morphology of Detroit. It could be said that the rail system was incorporated into the grid.

6. URBAN RENEWAL PROJECTS OF 1963

Projects led by the Detroit City Plan Comission

Public Lands Plan: Vacant Land

Within its 139 square mile territory, Detroit contains 24 square miles of vacant lands, not including the city’s park land nor accounting for the parcels that have been returned to productive uses. Those parcels were once occupied by housing units, businesses, or industry plans. Today, they are mostly small lots distributed within the neighborhoods; 72,173 of those vacant parcels are publicly-owned.

Housing

Housing Type:

92% Detroit’s housing stock was built before 1980.

73% of the city housing is made of single-family house which define Detroit city housing structure.