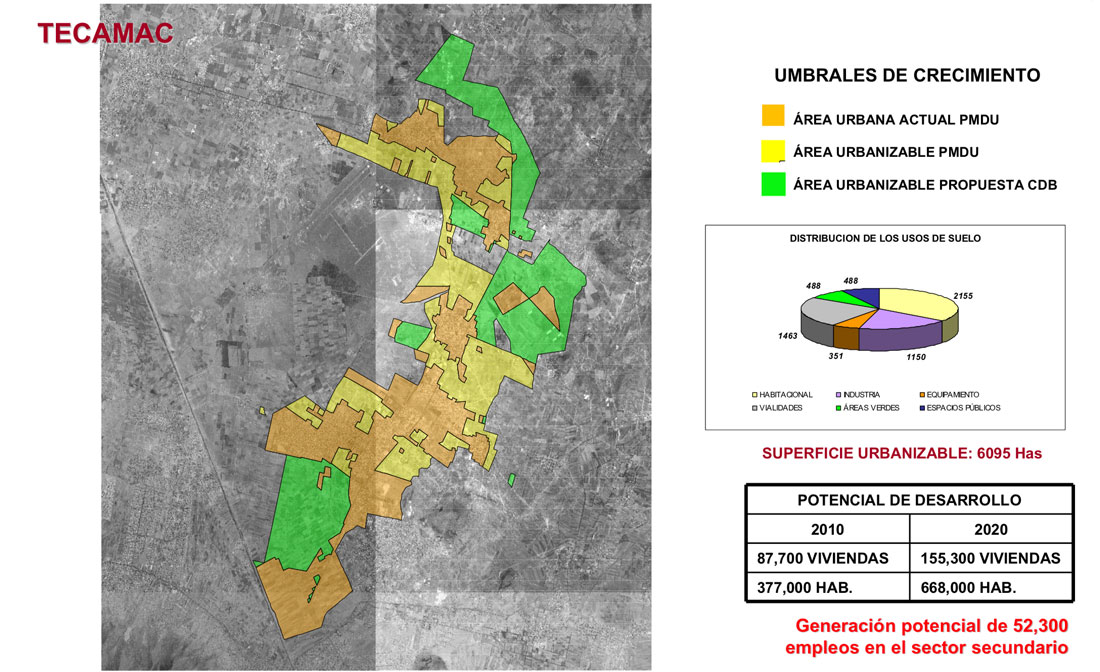

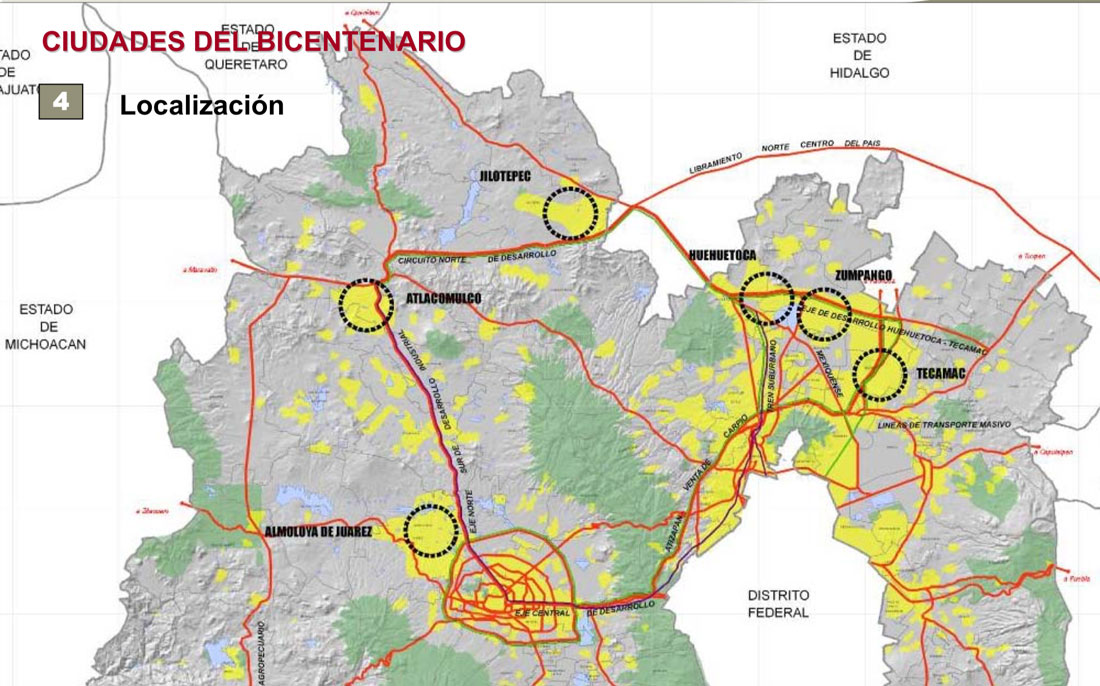

In 2005, as a way to increase its competitiveness, the government of the border state of Mexico City – Estado de México – launched a program called “Bicentenary Cities”, with reference to the 200th anniversary of Mexican Independence. This program proposed a careful land-use plan and the creation of a state structure for key population centers, all of them selected on the basis of location, capacity to receive population increase, potential to host infrastructure and strategic facilities, and the possibility of creating adequate communication lines to enable regional, statewide and national integration.

The program, part of the strategy developed by the administration of Enrique Peña Nieto – governor of the state at that moment, then president of the country, included six municipalities: Huehuetoca, Zumpango, Tecámac, Atlacomulco, Almoloya de Juárez, and Jilotepec.

Work-related self-reliance and the establishment of an urban settlement with sufficient services, medical, educational and recreation areas were forgotten promises of the “Bicentenary Cities” program. Neither the state nor the private developers – mainly Sadasi, Urbi and GEO – fulfilled their commitments. The explicit aim of building a model city that would be self-sufficient, well planned and highly competitive got lost amid the change of governments and the uncontrolled growth of housing.

Already in 2013, the abandonment and deterioration of many of the houses was noticeable. Water scarcity, the inadequate provision of basic services, a lack of employment and mobility problems were some of the reasons why a lot of families left the area and went looking to build a life somewhere else. At that time, between 520,000 and 550,000 houses were already uninhabited.

However, the conflict was just getting started. To this day, even though the infrastructure and services are insufficient, and even though Tecámac, Zumpango and Huehuetoca have been described as municipalities with high crime rates, especially because of feminicide , housing units are still being built with the consent of the state.

Following years of studying architecture and a natural interest in the city as a subject matter, Zaickz Moz has found in photography a way to explore the spaces, dynamics and social conflicts around him. The identity and community sense of peripheral settlements, the process of rebuilding houses after the earthquake on September 19, 2017, how to include ecotechnics into educational programs for primary schools, among others, are issues the photographer has approached through a variety of projects.

With his photo-essay Non-Social Interest (2018), Zaickz Moz presents a collection of back views of one of the failed bicentenary cities: Tecámac. Motivated by the chaotic views during his everyday journeys (México-Pachuca, Pachuca-México), he decided to investigate further and found a very complex urban and social conflict.

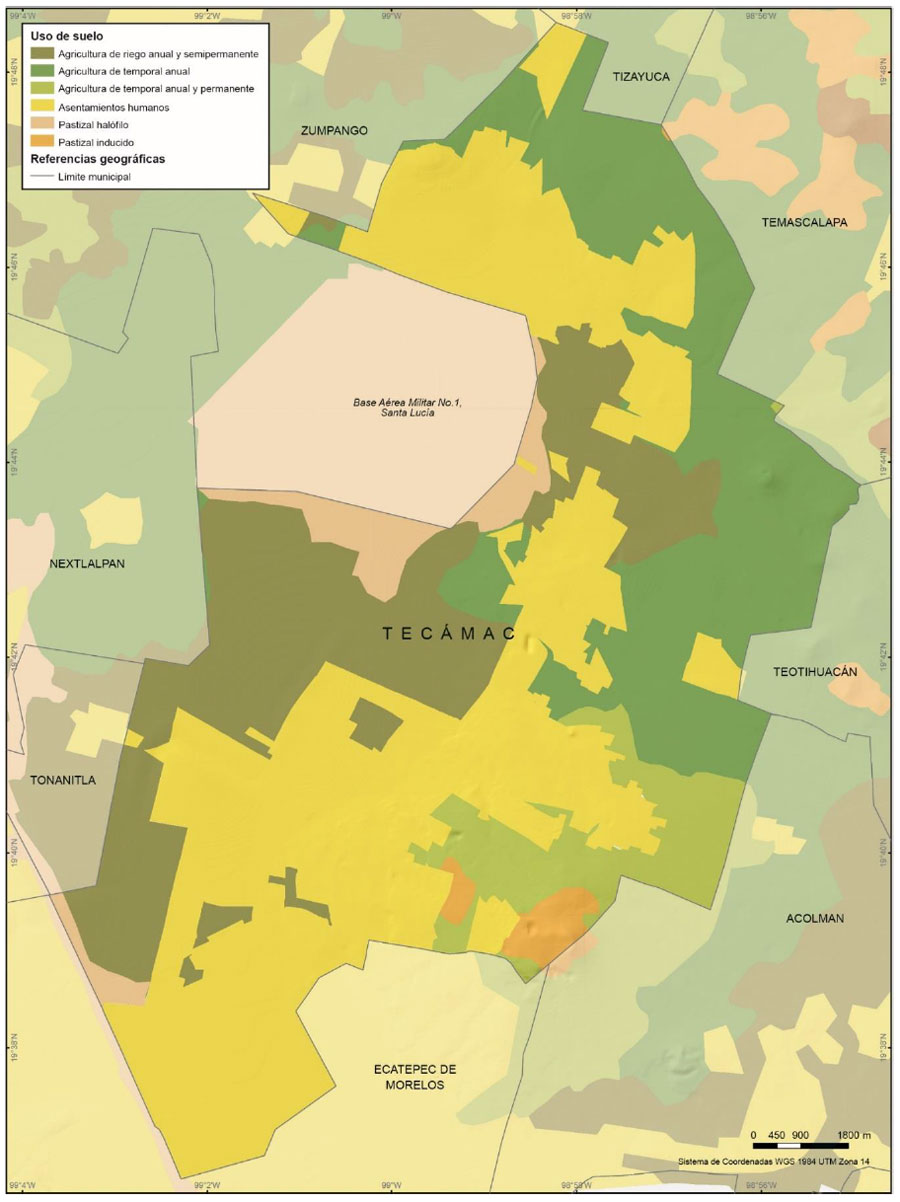

Although Tecámac’s housing development started in the late 1960s and kept going through the 90s with the construction of different neighborhoods, it wasn’t until it was named a bicentenary city that, within a new state regime of social construction, private investment carried out the project and detonated the housing boom that overran not only the allocated lands but all the surrounding area of Mexico City.

Figures reveal another chaotic and concerning view. Within a total area of 153.42 km2, Tecámac’s population went from 11,971 in 1960 to 446,008 in recent days. In 2010, 26 out of every 100 dwellings were abandoned and although the situation (no jobs, no mobility, no infrastructure) has not improved, building permissions are still being given out: from 2018 to the first quarter of 2019, 55 new housing developments had been authorized. And there is more. Paradoxically, in 2015, the municipality’s overcrowding index was 3.64 inhabitants per dwelling, which according to the Índice de Calidad Global de la Vivienda (Global Housing Quality Index) is considered midrange overcrowding.

In security terms, the picture is not much better. According to municipal data, in 2018, 7,814 crimes were registered, which gives a total rate of 1,752 crimes for every 100,000 inhabitants.

So, there is not enough water, drainage systems are failing, there are no local jobs and means of transportation are insufficient. Some people have left, looking for a better life somewhere else, but there are others – those without any other option – who, despite everything, have stayed. Non-Social Interest talks about them.

The back views of Tecámac’s housing settlements, taken from the México-Pachuca highway, portray the action of the inhabitants who, through self-construction, overlapping levels and changing the original buildings, have adapted their houses to their living needs without a construction plan or any concern for safety standards.

Vertical expansion, variation of materials, windows in the surrounding walls, exposed stairs, security fences… The constructive disorder captured by Zaickz Moz’s photographs is the result of a serious disarray, in which the public and the private remain confronted – a disarray affecting the living conditions of families and communities, the environment and, also, the thousands of people commuting every day from peripheral areas into Mexico City.

The issue is not only the lack of urban infrastructure and the insecurity caused by the abandoned areas and the failing social fabric, there is also the risk associated with unplanned, unsupervised domestic construction.

The Tecámac Code of Regulations states that every architectural project, build or modification process of every type of construction shall be subject to federal and state rules and will require a municipal license. Unfortunately, these regulations –and non-compliance with them – are not new.

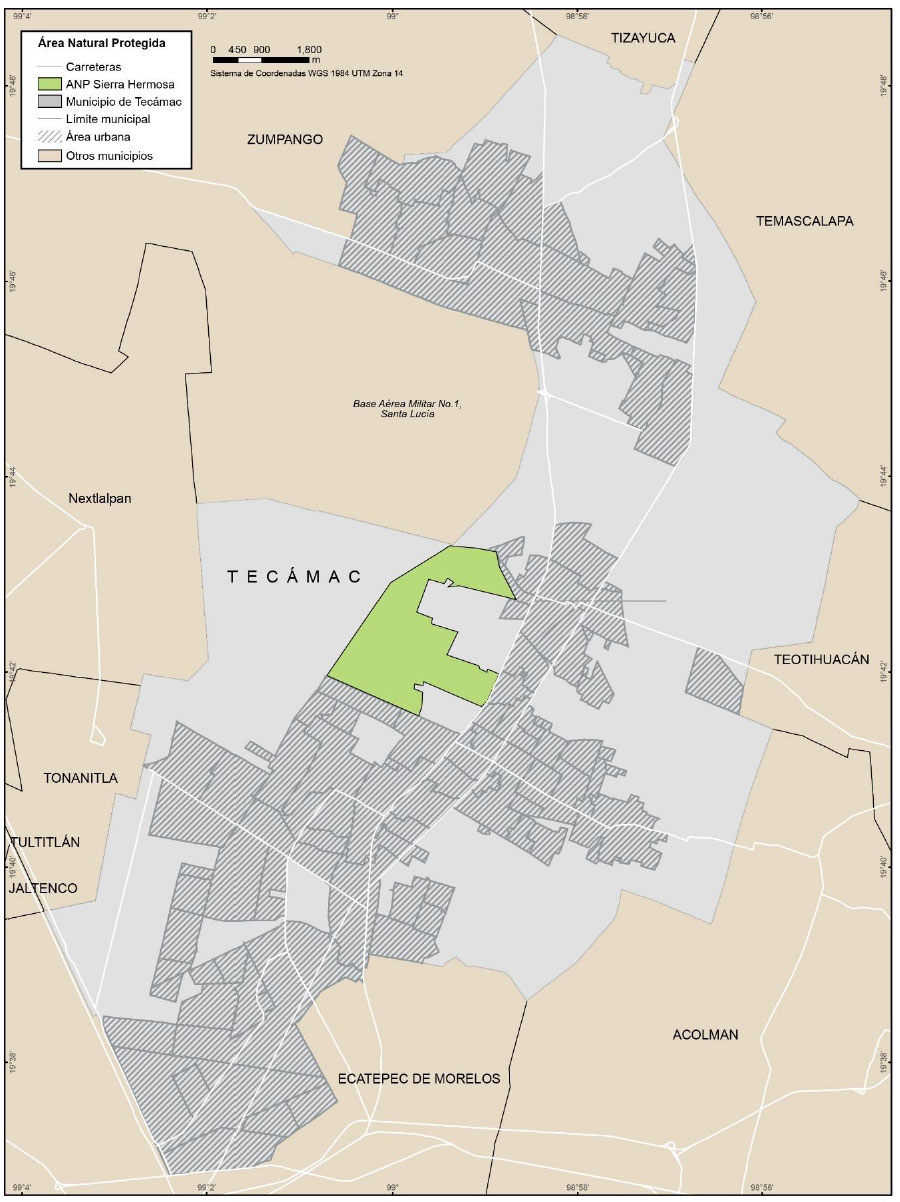

With the motto “Thriving and Secure City”, Mariela Gutiérrez – the current municipal president (2019-2021) – has established a course in the Tecámac Development Plan, based on proper planning and powered by citizen participation. With regard to the organization and sustainability of the municipality, she recognizes that one of the biggest issues the administration faces is urban sprawl. She aims to update the Urban Development Plan and redefine the boundaries of urban expansion in order to create a more compact city, with a higher population density and more economic activity.

In the same document, she proposes to work toward sustainable housing from the economic, ecological and social dimensions, committing herself to ensuring that everybody has access to a house with adequate basic services, while improving slums and providing “security with a citizen-focused approach”.

In recent days, a presidential decision unleashed a controversy related to the locality: the new international airport construction on the military air base in Santa Lucía – surrounding the municipalities of Tecámac and Zumpango. While in Mariela Gutiérrez’s view the project will focus the economic vocation of the region, creating opportunities for entrepreneurs and corporations that will provide well-paid employment and plenty for the tecamaquenses , communal authorities and other civil groups are using legal resources to submit the disposition to public consultation. They are against the project because of its environmental impact and because of the problems related to water and other services it will bring, not only during the construction but in its everyday operations.

The issue is not merely housing development anymore. Its complexity is growing and, as often happens in México, multidimensional solutions probably will remain unfulfilled. However, the effects and the dangers of the situation are not just numbers in a development plan or a news story. There are people living – and actually fighting – everyday to circumvent them.

Focusing on just one of many examples of irregular developments around big cities in México, Non-Social Interest notes the consequences of neglect and a disregard for regulations. On the one hand, the inhabitants take over responsibility for their own welfare, turning their backs on public order and space. On the other, the government – absent, detached or incompetent – continues using the back walls for their political ads and campaign promises.