Although the concept of a network is fundamental in all the contributions we have analyzed thus far, the information revolution has allowed for operating with networks based on an interactive – or performative – condition, rather than a merely structural, symbolic, material or formal understanding. In this sense, the notion of Net-Building can be summarized in two main points: cooperativity with other buildings and interaction with the environment.

These aspects are essential when it comes to the experimental architecture characteristic of distributive protocols. For this reason, iconic architectural designs such as Toyo Ito’s “Sendai Mediatheque” (1997) cannot be explained from a distributive perspective, despite their repeated allusions to the network concept. Specifically, on the one hand, Ito’s project presents a program that is particularly dedicated to the world of information and, on the other, its immaterial appearance alludes to the evanescence of data flows. However, both attributes function allegorically: on the one hand, their understanding of information is not performative but programmatic; and, on the other hand, there is no operative interactivity either with the user, with the immediate surroundings, or with the environment.

These characteristics in no way detract from its disciplinary contribution to architecture, but they do set it apart from an advanced understanding of architecture or, at least, a distributive interpretation. Something similar is the case with projects such as “14 billions” by Tomas Saraceno (2009) and “Floating Landscapes” by Numen (2011). In both cases, the networks do not serve as operative resources but rather as material structures, removed from any informational condition. The same can be said of projects such as the “Serpentine Gallery” (2004) or the “Omotesando Building” (2004), both by Toyo Ito: they also apply the idea of a network but, again, it is not from an informational point of view but a structural one.

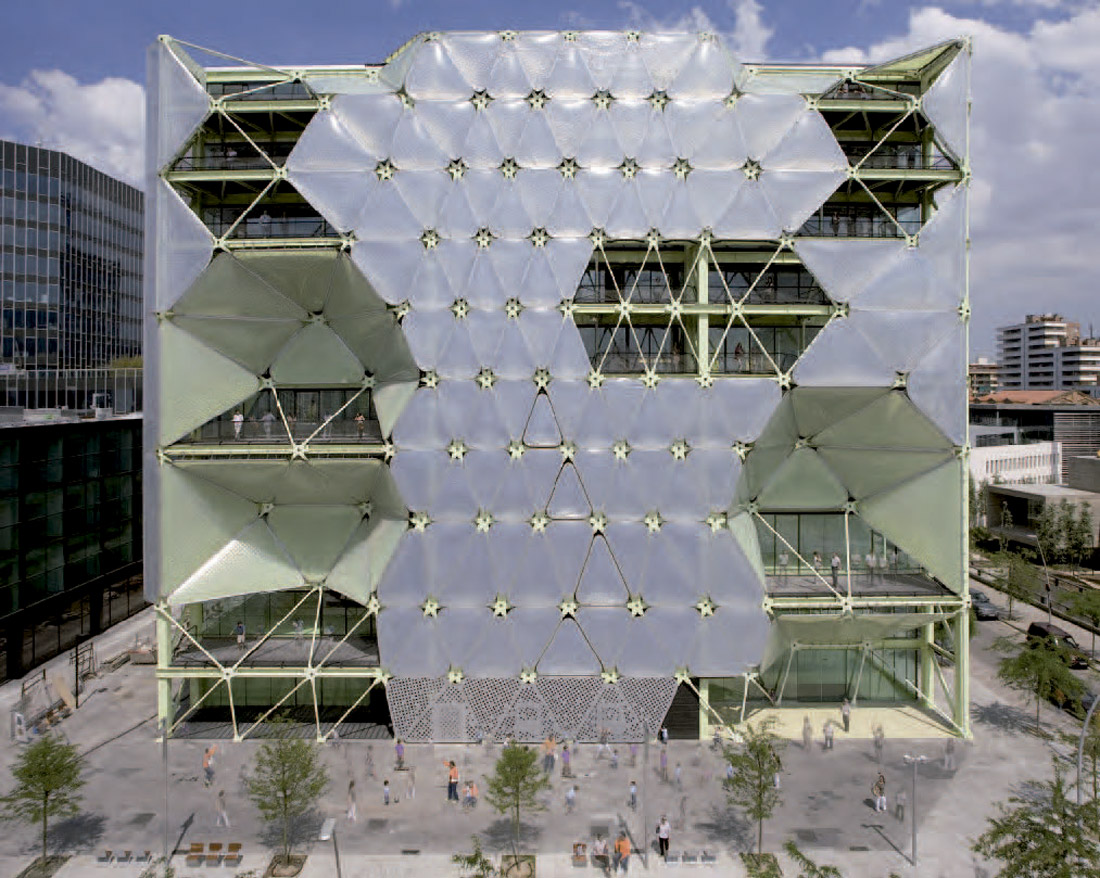

In opposition to these projects, the “MediaTIC” building (2010) by Cloud 9 represents an emblematic example of a Net-Building. Although a “layered” reading of the project is possible, which means it can be described in terms of conformative complexity, approaching the design from a distributive perspective reveals issues that resonate with Jeremy Rifkin’s “The Third Industrial Revolution” (2011): buildings as power plants, renewable energy sources, connection to smart grids, etc.

However, beyond the building’s networked operativity, the project has a reactive capacity that combines two characteristics. On the one hand, it operates through performative interactions: the building adapts its façade depending on the climate conditions. On the other hand, this interaction takes place between different ecologies: the project interacts first with the surrounding environment, second, with its own interior climate requirements and, third, with the other buildings around it (the 22@ district). The cubic building’s formal simplicity further emphasizes its function as a distributive node, while it adopts the typical technological solutions used in such systems, including Arduino devices in the sensors or a program dedicated to ICT.

In that sense, the design’s objectual function distances it from the topological formulation characteristic of conformative protocols: the idea of a continuum is not understood in formal terms, but in collaborative terms. On the other hand, the use of a lightweight tensile structure emphasizes the immaterial dominance of a reality in constant flux, where connections are more important than the weight of materials, which seems to illustrate some of Latour’s assertions regarding the inconsequence of actors when compared with the relevance of their role as participants in an exchange network.

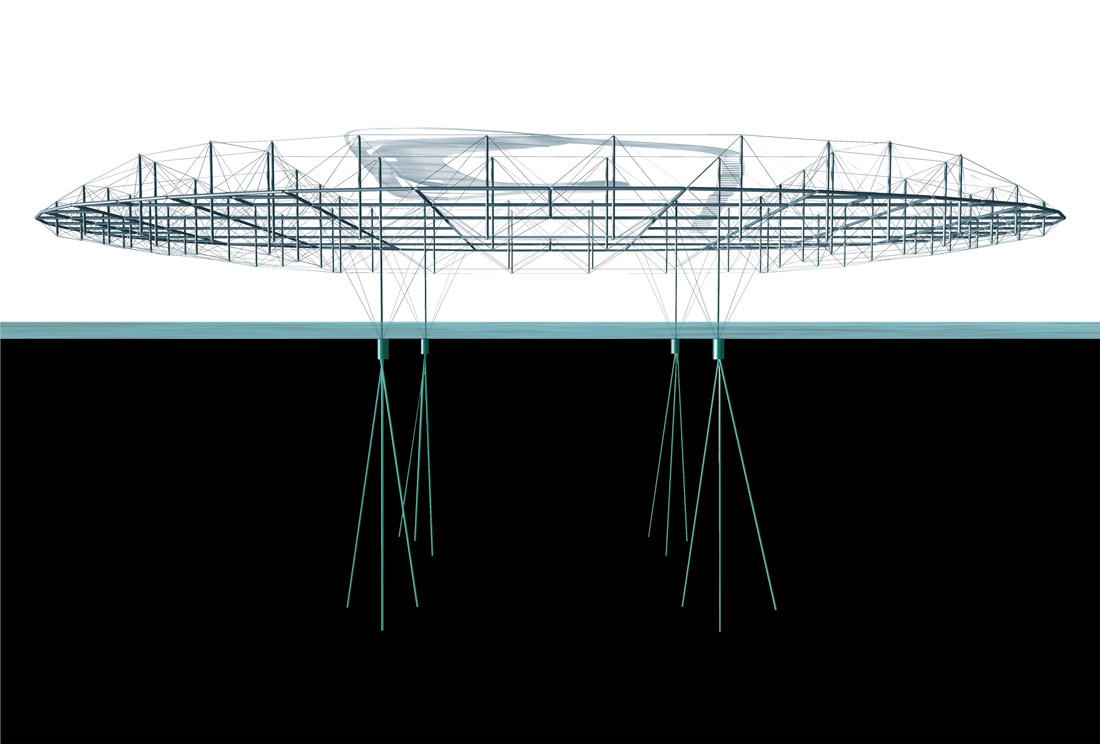

The New York Aquarium designed by the same author follows similar distributive patterns, although here it draws on the formal fluidity associated with water. Slightly earlier works like Nicholas Grimshaw’s “Eden Project” (2000) or the PTW Architects’s “Water Cube” (2007) also display distributive characteristics. Both projects contribute to the production of a collaborative multidisciplinary cluster, which is the hub for dozens of technologies, publications and projects. However, although the “MediaTIC” building and the “Eden Project” share a distributed approach, both projects are traversed by completely opposite understandings of nature’s notion. Geli’s nature is what Zizek would define as a techno-nature18: a manipulable entity that can and should be altered by humans in order to achieve their goals, sustainability and self-sufficiency among others. In the case of Geli, this approach is based on the concept of “particle”, understood as the ultimate element of reality and therefore a powerful tool to manipulate it. Instead, the Eden Garden operates with a deeply conservative approach to nature: as its name suggests, nature is seen as a harmonious and divine origin that needs to be preserved rather than altered, which is the main role of the domes.

Besides, and opposing the faustic desire for extroversion characteristic of propagative projects such as Diller-Scofidio’s “Blur Pavilion” (2003), the domes are rather introspective, constituting an unidirectional relation in which there is almost no hygrothermal impact on project’s surroundings. However, as we will see soon in detail, this decade has witnessed a way more radical notion of environmental interaction that the one offered by “Eden Garden”. The emergence of design softwares like “Grasshopper” (2007) incremented – both quantitatively and qualitatively – users’ ability to interact with their surrounding by making it easier to manage external data. This extroverted attitude is precisely what makes it possible for projects like the ones we have just mentioned to be constituted through their interactions with other nodes – in this case environmental ones – and not only with themselves, as was the case with NOX’s “Water Pavilion”. Contrasting with the earlier “conformative protocols”, the designed environment functions here as an operational context rather than as an inert container.