The project for the extension of the Unterlinden Museum in Colmar encompasses three dimensions: urban development, architecture and museography. It centers on the issues of reconstruction, simulation and integration.

Urban development

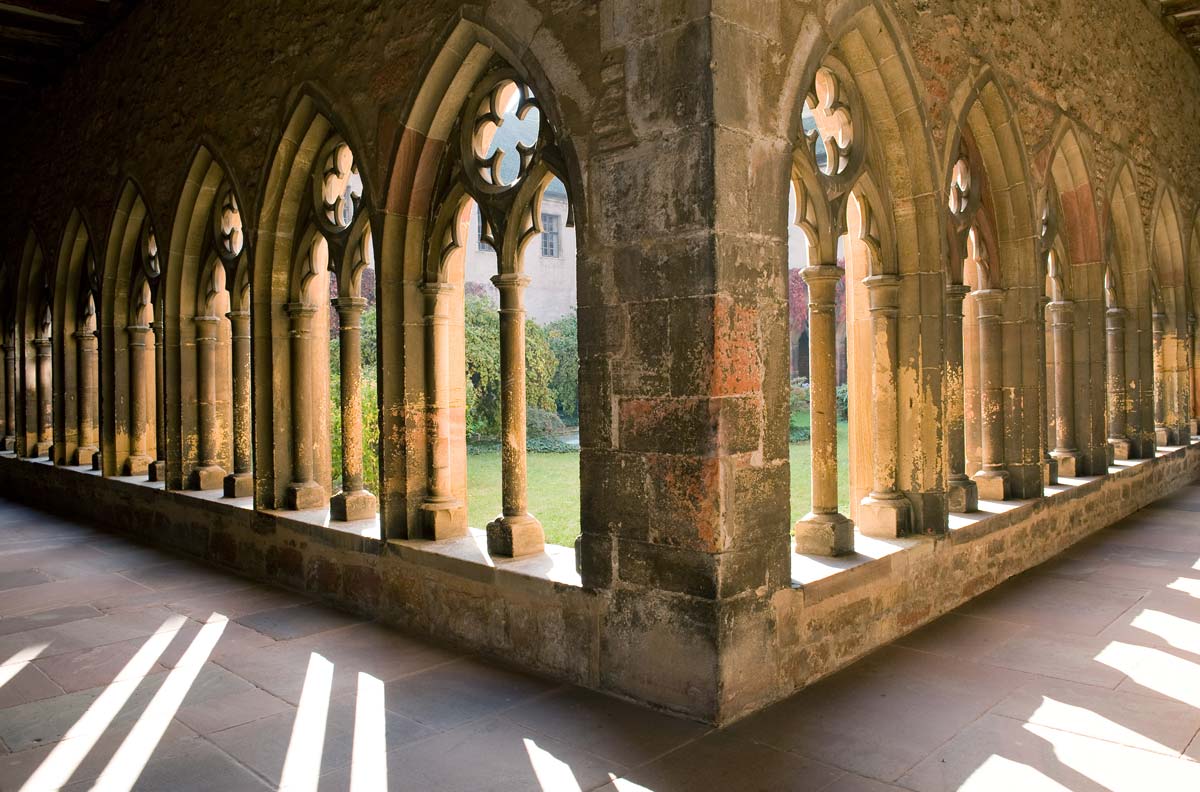

After the extension, two building complexes, physically connected by an underground gallery, face each other across Unterlinden Square. The medieval convent consisting of a church, a cloister, a fountain and a garden stand to one side. On the other side of the square, the new museum building mirrors the church’s volume and, together with the former municipal baths constitutes a second, enclosed court.

Between the two museum complexes, Unterlinden Square has recovered its historical significance, recalling the times when, across from the convent, stables and farm buildings formed an ensemble known as the “Ackerhof”. The bus stop and parking lot existing prior to the museum’s renovation have now become a new public and urban space. The Sinn canal, which flows under Colmar’s old town, has been reopened, becoming the central element of this new public space. Close to the water, a small house marks the museum’s presence on the square: its positioning, volume and shape are those of the mill that once stood there. Two windows allow passers-by to look downwards at the underground gallery connecting the two ensembles of buildings.

Architecture

We were looking for an urban configuration and architectural language that would fit into the old town and yet, upon closer inspection, appear contemporary.

Moved to the centre of Unterlinden Square, facing the canal, the entrance to the expanded Museum leads to the convent, whose facade has been delicately renovated. The renovation works were carried out in close collaboration with the architects of the French national heritage department. Museological components from the recent past were removed and the spaces restored to an earlier state. We revealed original wood ceilings and reopened formerly blocked windows looking out on the cloister and the city. The church’s roof has been renovated, and a new wood floor installed in the nave. Visitors walk down a new, cast concrete spiral staircase leading to the underground gallery that connects the convent with the new building.

Inside, we decided to design the underground gallery and the new exhibition building (now called the “Ackerhof”), which present the 19th- and 20th-century collections, along contemporary, abstract lines. The space on the second floor of the Ackerhof is dedicated to temporary exhibitions: its gabled roof and exceptional height (11.5 meters) reflect the proportions/volumes of the Dominican church standing opposite. The central space of the former municipal baths, the swimming pool (“La Piscine”), is now connected to the new exhibition spaces. It serves as a venue for concerts, conferences, celebrations and contemporary art installations. The other spaces of the former baths house the administration of the museum, a library, a café facing the new courtyard and the Colmar Tourist Office facing Unterlinden Square.

The Ackerhof and the small house have facades made of irregular, hand-broken bricks, entering into dialogue with the convent facades in quarrystone and plaster that were redone many times over the centuries. A few lancet windows have been cut into these brick walls; the roof gables are in copper. The new courtyard is paved in sandstone, as is Unterlinden Square, while the enclosing walls are made of the same brick as the new buildings. At the heart of the courtyard, an apple grove—the “Pomarium”—arises from a platform made of stone and brick.

Collection and Museography

In close collaboration with Jean-François Chevrier and Élia Pijollet, as well as with the museum’s curators, the museography and the architecture were developed hand in hand. The collections comprise works of worldwide renown from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance—most notably, the Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald and Nicolas von Hagenau (1505-1516)—as well as designs, prints and patterns for the production of textiles, photographs, paintings, sculptures, faience pieces and ethnographic objects from the 19th and early 20th centuries, with a focus on local art and art history. From the 1960s onwards, a modern art collection was built up. As to the Isenheim Altarpiece, it remains in its original if more light-filled and less cluttered convent church location, although its presentation frame has been replaced by a sober steel structure. This makes the painted wood panels look more like artworks. Eleventh- to sixteenth-century paintings, sculptures, small altars and artifacts are on display on the neighboring ground floor and in the cloister. The downstairs floor presents the archaeological collections.

The underground gallery consists of a succession of three very different exhibition spaces. Beginning the circuit, we have the history of the Unterlinden Museum, covering a section of 19th-century and early 20th-century works. The second gallery displays three of the Museum’s most important pieces: located under the little house, this room represents the core of the expanded Unterlinden Museum, uniting the project’s three dimensions: urban development, architecture and museography.

On the first and second floors, the new building represents a loose chronological sequence of the 20th-century collection. Interconnected spatial units organize and structure the floor’s overall volume, rather than subdividing it: here works or groups of works are exhibited in relation to one another.

Together with the museography for the collection of 20th-century art, the inaugural exhibition (from January to June 2016), curated by Jean-François Chevrier, will serve as an outstanding example of the uses to which the newly acquired spaces can be put, while presenting an exemplary reading of specific pieces from the Collection.

The interplay between city planning, architecture and museography renders the Unterlinden project most exceptional: one leads to the other. From the angle of urban development, the most decisive contribution is the enhancement of the formerly desolate zone between the cloister and the former public Baths. Then, the opening of the formerly covered canal provides an attractive site for Colmar: it is here that the entrance to the new museum complex has been transferred. And still another exceptional aspect: only close scrutiny distinguishes the old from the new architecture of the complex’s various parts. Jacques Herzog, Senior Partner, Herzog & de Meuron.

The Unterlinden Museum is a truly international institution. On the one hand, its collection—together with, in particular, the Isenheim Altar— is an integral and central part of the cultural heritage of France on the periphery of which the museum is situated. On the other hand, the collection represents a core part of Europe’s cultural heritage as a whole, while also serving as an invaluable manifesto thereof. It is our hope that the Unterlinden Museum will come to be seen as an institution standing for the history of Europe, and this above and beyond any national boundaries. Pierre de Meuron, Senior Partner, Herzog & de Meuron.

Visitors will experience the expanded Unterlinden Museum as an organic, complex sequence of inside and outside spaces. In our profession, only rarely do we have the occasion to custom tailor architecture to such a degree, to a content that spans several centuries. We had a chance to simultaneously, and equally intensively, address changes to the urban fabric as well as the presentation of a single work of art. Christine Binswanger, Senior Partner, Herzog & de Meuron