One thing is certain about Beatriz Colomina and Pep Aviles’s Playboy Architecture, 1953–1979: It is an evidentiary display proving that architecture and media are complicit partners in shaping society’s view of itself. Born out of research within the Ph.D. program in Media and Modernity at Princeton University’s School of Architecture, Playboy Architecture is an exhaustive index of the ways magazines, architecture, design, furniture, fashion, and sex influence Western society. From the pages of Playboy, one could dream of a glossy packaged life. However, the role of the architect in this context has never been clearer: a precise purveyor of taste, a consummate expert on lifestyles, and a key to liberation—sexual and/or otherwise.

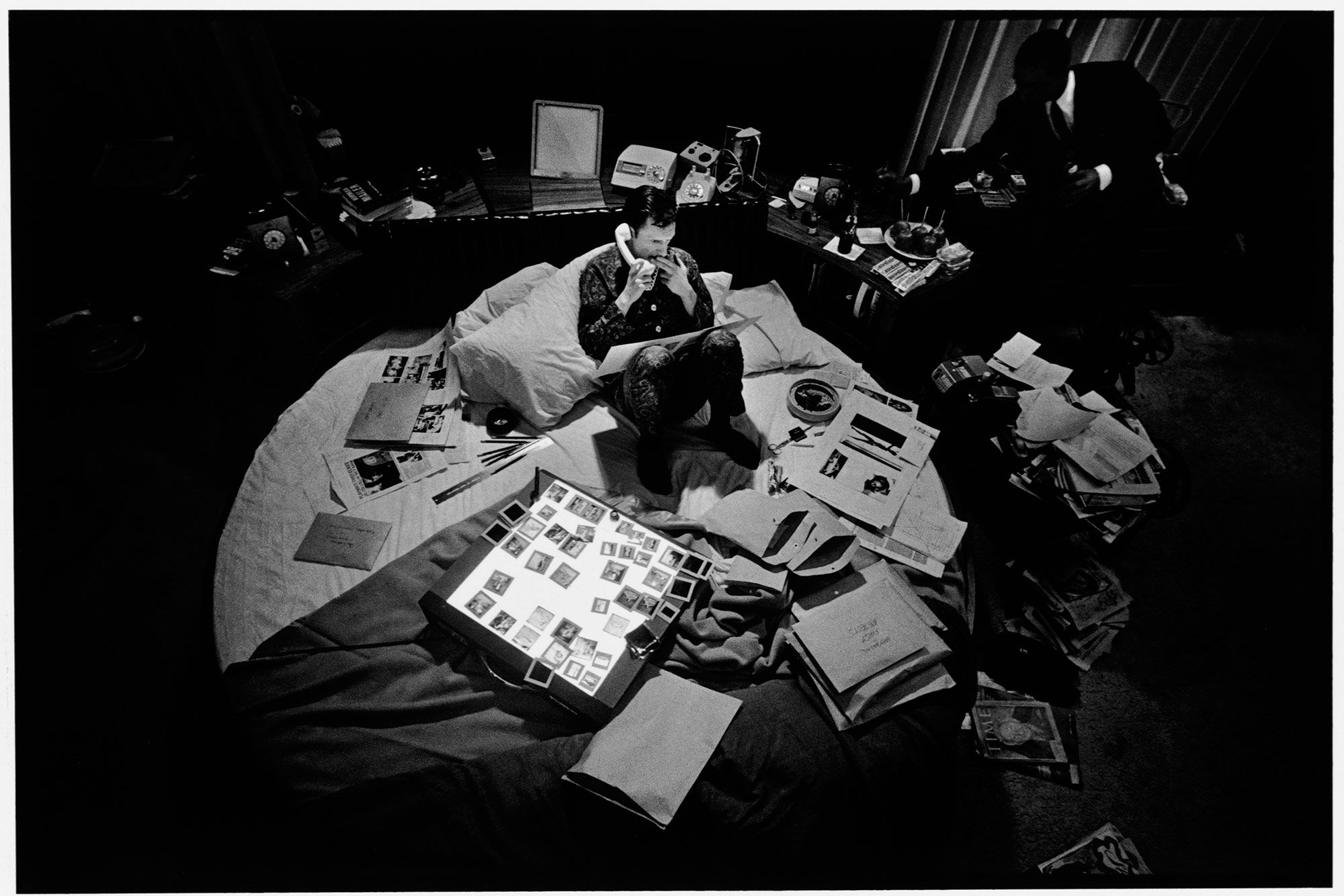

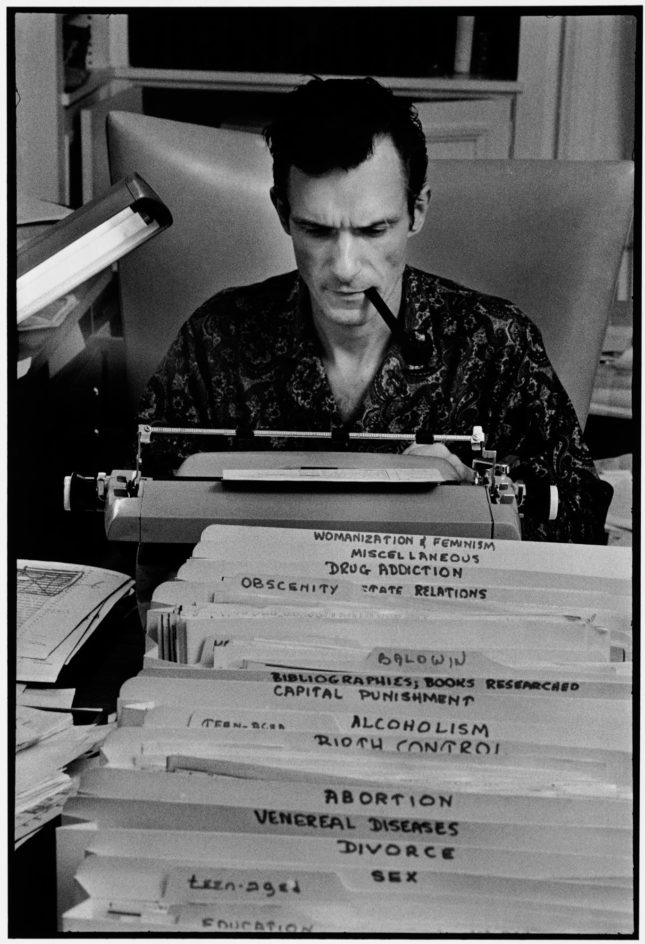

Hugh Hefner’s architecturally scaled bed doubled as an office. Courtesy Elmhurst Art Museum

On display through August 28 at the Elmhurst Art Museum in Elmhurst, Illinois, 18 miles west of downtown Chicago, Playboy Architecture is situated within Mies van der Rohe’s McCormick House, a centerpiece of the museum and one of three built Mies houses in the United States. Perhaps there can be no better space to display and curate a show like Playboy Architecture, simply due to the fact that this house was meant to be mass produced—a cog in a suburban machine that Mies was never able to create, in part because modernism and its sultry packaging were just not tasteful to the inhabitants of Elmhurst.

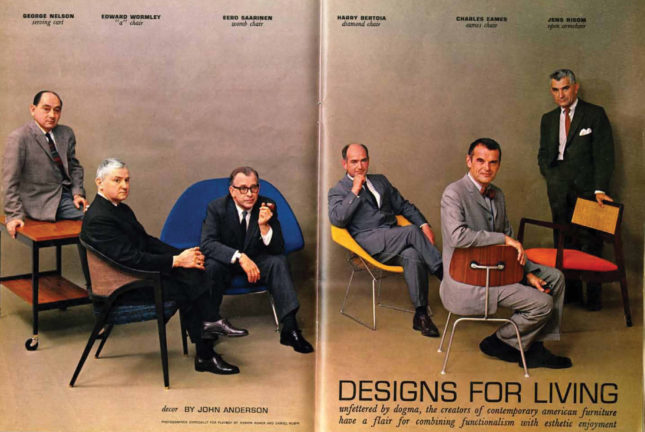

Playboy brought together many of its time’s greatest designers. Courtesy Elmhurst Art Museum

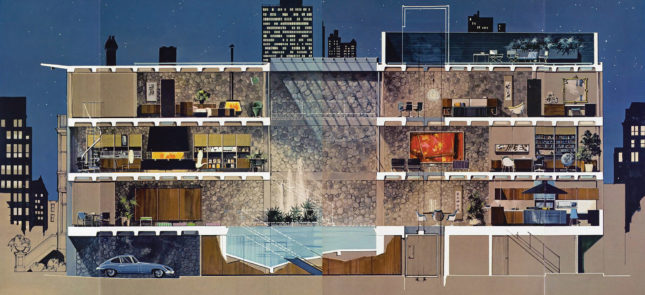

The show is divided into four parts: Playboy Pads, Vehicles + Mobility, the Bedroom, and Playboy Architecture. Shifting scales from beds to interiors and from airplanes to houses, the curators locate different punctuations of a complex “lifestylescape,” where design and architecture provide not only the backdrop to where you live, but also a proposition on how to live. The first room in the exhibition when you enter is the Playboy Pads, situated within the old living room of the McCormick House. Sitting on a circular pedestal are some iconic chairs, like Mies’s Barcelona, coupled with blown-up pages of Playboy showing drawings of different interiors. The most compelling pad shown is the one-inch-by-one-foot-long sectional model of the proposed Playboy House in the Gold Coast of Chicago, which is three stories and divided in the center by a pool with a water-to-glass-ceiling atrium, allowing for views through adjacent windows all the way up—a truly panoptic voyeurism.

The next room shows Vehicles + Mobility: Hugh Hefner was famous for living and traveling in style. A vertically displayed plan-section model of an airplane gives an incredible glimpse into the almost Corbusian floor plan of walls within, replete with the creature comforts of high modernism, extending lifestyle during commutes to other far away pads.

Courtesy Elmhurst Art Museum

In the adjacent room, lies a bed. The Bedroom—or, more specifically, a circular bed—is hidden behind a velvet curtain with peepholes, dimly lit and perhaps the most compelling piece of design in the entire exhibition. This bed was not only meant for the purposes of sleeping and sex, but also was an office and a conference center with shelves and phones, but no chairs. The bed extended past its typical uses and became an ambiguous small architecture in and of itself, suggesting that the real place of modernity in society was to help it reinvent itself, one bed at a time.

Courtesy Elmhurst Art Museum

Finally, viewers enter Playboy Architecture, situated inside the old kid’s playroom of the McCormick House, albeit non-ironically. This section gives users a glimpse into built residential and visionary housing projects. Matti Suuronen’s portable metabolist Futuro House, John Lautner’s Elrod House, and Ant Farm’s House of the Century are all shown as “evidence of an ever expanding blurring between modern design and pleasure,” according to Colomina.

Courtesy Elmhurst Art Museum

The physical and conceptual thread that ties all the rooms together is the original magazines themselves, complete with white gloves to handle them carefully. The back and forth between the curated magazine and the modernist McCormick House provides a ripe environment to imagine oneself within the image of modernism. Playboy has always been equated with male sexual pleasure, but Colomina’s curation suggests a much deeper understanding of the relationship between sexuality, architecture, and design, not from a purely objectified space, where this exhibition might be misunderstood to be, but from a transcendent redefinition of oneself fittingly tied into the construction of lifestyle. This inversion is a critical product of the exhibition curation that directly challenges our historical understanding of Playboy, and uses the revolutionary edge of modernist architecture to suggest that creating future images of visionary, free spaces for anybody is what architects have, can, and should continue to do.