The design of housing remains one of the least researched areas within the current debate in the United States – this despite a recent era of massive growth in the housing market. With the focus of development being in the suburbs, a good deal of building has fallen into the hands of developer/contractor alliances – and often without the agency of the architect. Meanwhile, much of the current work in the inner cities has been entrenched in the politics of compromise, negotiations with local communities and design review boards, coupled with the aesthetics of “simplistic” contextualism. Other more progressive work has adopted aggressive iconic ambitions, while leaving typological, spatial and integrative research behind. The process that democracy requires can tolerate neither an architecture of idealism, on the one hand, nor of negligence or innocence on the other. Between developer/contractor alliances and the “design by committee” processes, the architect can no longer overlook this cultural predicament if she or he is interested in engaging in the terrain of housing once again.

In the Macallen building, the ‘design’ of the budget was a driving force in coordinating typological, spatial, and aesthetic considerations, and the knowledge of the means and methods of each trade was central to an integrative design process. Equally importantly, the design strategy was to engage the developer and construction manager relationship, up front, as a way of addressing specific trades, systems of fabrications, and pro forma criteria, foregoing the traditional value engineering process.

A New Public Common: The Raised Green

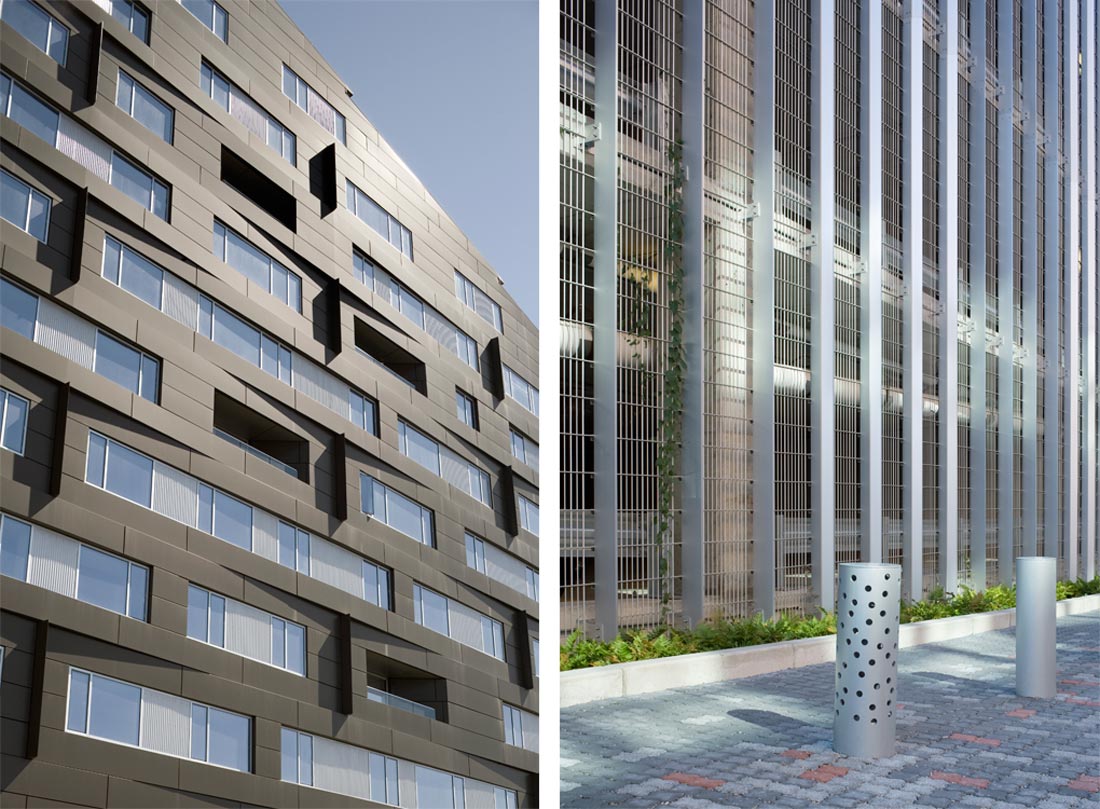

The building meets the street on Dorchester Avenue with storefront units, which are designed as retail, commercial spaces, or artist lofts. On the north edge, we introduce a new street, giving access to both this building as well as the now-famous Court Press Building, which has recently been renovated. Our proposal has a canopy that covers a pedestrian passage, connecting Dorchester Avenue to two points of entry into the building, alongside the garage. The garage is screened from the street by means of a green wall, a layered façade composed of metal ribs, mesh, and wire that will sponsor the growth of ivy. Most importantly, on top of the garage, there is a common court, a semi-public open space for the residents of the two buildings: the Macallen and Court Square. The courtyard contains a garden, a swimming pool, a public deck, and seating areas with ample shading. The courtyard is supported by other public amenities: a common room, a theater, and a gymnasium. The courtyard is also part of the various green features of the building: expanding the natural flora of Boston, controlling storm water drainage, adopting photosynthetic replacement, and mitigating the heat island effect.

Massing: Morphogenetic Ascension

The form of the Macallen responds to its urbanistic circumstances in specific ways. We propose a single building of ascending height. To the east, the height of the building matches that of other buildings on Dorchester Avenue, while to the west, the building rises to the maximum allowable height, responding to the scale of Boston’s skyline. A single figure, sphinx like, the form reconciles the relationship between its parts and the whole. Thus, the building extends the street life of South Boston on its eastern edge and participates in the rejuvenation of the fabric and its growth. At the same time, on the railroad tracks to the west, the building operates primarily at an iconic level; visible from the highway, from downtown, and from historic South End, the scale of the building corresponds to the regional and creates a strong threshold into South Boston.

Greening Housing: The Transformation of a Building Type

The Macallen building is designed with certain principles of smart growth, while also producing a green building, projected towards gold certification. While residential buildings traditionally refuse green strategies with any ease, this building is replete with some basic components that secure its certification. Among the various strategies, the green roof is featured as one of the most prominent elements, controlling storm water drainage, contributing to photosynthetic replacement and creating thermal mass separation helping towards evaporative cooling. This, in turn, also helps to overcome the heat island effect. The roof is covered in sedum of various kinds and colors. Sedum requires no special attention or added irrigation, and thus it is self-sustaining. Its sloped surface becomes a fifth façade for the building, reading as a raised landscape in the skyline of Boston. Given the peculiar form of the building, the units adjacent to the diagonal spine take advantage of this proximity to carve out private outdoor spaces and create outdoor rooms next to their dining rooms.

Beyond the green roof terraces, the design incorporates other sustainable techniques within the LEED point system: the use of recycled materials, water-saving strategies, good indoor environmental quality, using rapidly renewable resources, accounting for life cycle costs, and many other features. Being no more than a block from the Red Line T station, a 10-minute walk from downtown Boston, and a 15-minute bike ride from Cambridge, the site is ideally suited for smart growth, giving its inhabitants a myriad of opportunities to forgo the use of cars.

A Structural Predicament: The Shear Wall and the Shish Kebab

Given the program of the building – to provide for the maximum diversity and flexibility of lifestyles and living arrangements – the traditional stacking of units is made impossible by the staggered truss system. To that end, we recess the service elements of the units (the baths, kitchens, and cores) along the building’s spine so as to open up the inhabitable spaces next to the façade. In turn, the units are correspondingly staggered on top of each other, diagrammatically like large masonry units, entangling the units within the logic of the staggered truss.

More importantly, we make sure to vertically skewer – and thus import the logic of the shish kebab – each unit with plumbing and mechanical shafts (forgoing arm-overs) to secure the maximum efficiency for a building of this type, without which a building of this scale would not be possible. Thus, we are able to pierce heterogeneous sets of elements and bind them into a singular logic, a function provided by the combination of the mechanical shafts and the varied units. This logic radicalizes the building’s flexibility to provide for varied units: there are one-, two- and three-bedroom units, there are lofts, duplexes, triplexes, and townhouse units. There are also garden suites on the public court.

Over the course of the design process, the market indicators changed several times, and thus the layout of the units changed correspondingly. Thus, the idea of the building’s flexibility was actually made evident within the context of the design process.