London made good splash at the inaugural Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism which opened at the beginning of September in Zaha Hadid’s DPP Cultural Centre. Taking one of the Biennale’s themes of ‘The Productive City’ the London installation showed a film curated by We Made That and director Alice Masters which explored the complex thread of suppliers, from costumiers to scenery makers, that are needed to deliver a production in the Barbican arts centre. The film featured interviews with the artisans, creatives, manufacturers and suppliers, who contribute to London’s role as a productive city.

Industrial activities are facing increasing housing and land value pressure in “London. Charlton Riverside Employment and Heritage Study,” 2017. We Made That for Royal Borough of Greenwich and Greater London Authority. Photo by Philipp Ebeling.

London is well established as a productive city. Making and manufacturing can be found in many different parts of the capital, reflecting a wide range of sectors, from beer to bicycles and fashion to furniture.[1] Combined with logistics and other light industrial urban services, these play a vital role in London’s economy, delivering the goods so essential for the capital to thrive. The city is home to a diverse range of workspaces, from converted warehouses to newly built industrial spaces and small-scale design and artist studios.[2] These support and sustain a huge array of industrial, urban service, and making activities.

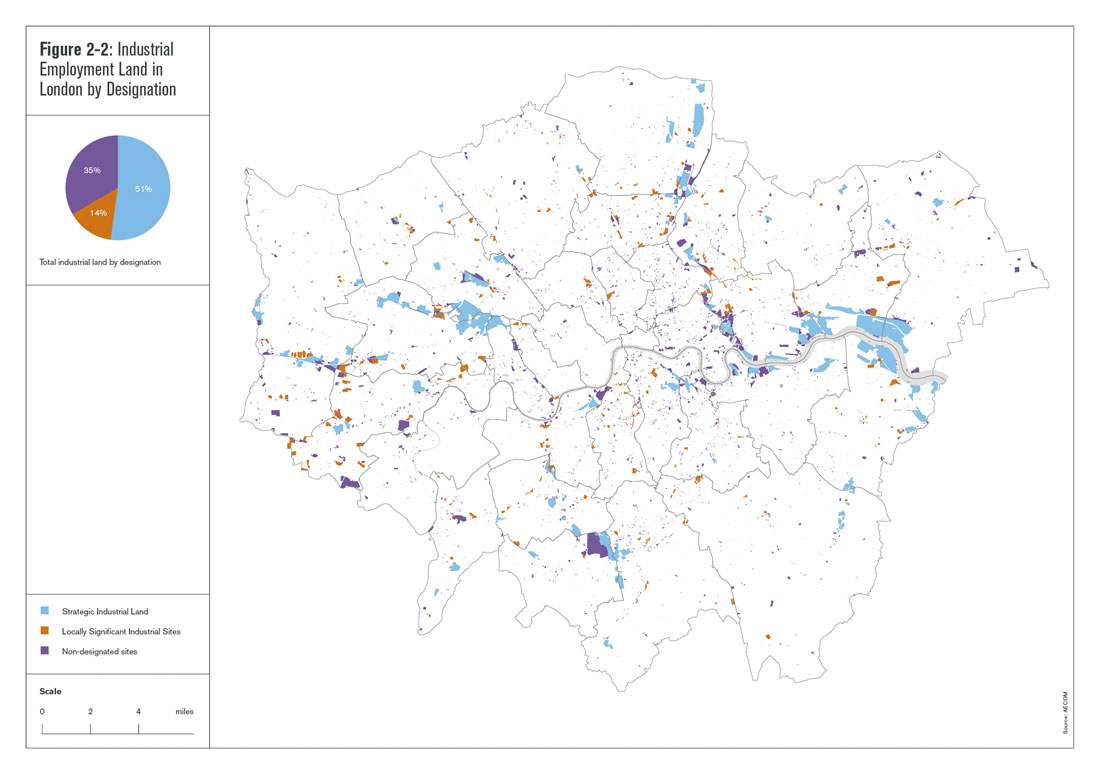

London’s industrial land as of 2015. Since 2001, 1,305ha of industrial land has been released to non-industrial uses. “London Industrial Land Supply and Economy Study,” 2015. AECOM, Cushman & Wakefield & We Made That for Greater London Authority.

While there is much to celebrate, London is losing space for production and industry. The need to house a growing population within a constrained city region, and the resulting loss of industrial land [3], is reducing the city’s capacity as a place of production. In the context of London’s now well-documented loss of designated industrial land manufacturers, food processers, urban logistics, and local service businesses are facing uncertainty about how they fit into London’s future. It is more important than ever to defend London’s industrial places and spaces. There is a need to think more imaginatively about what these sites can accommodate and how they might be adapted to keep existing and additional productive uses on site. Industrial sites are too often dismissed as “underused” parts of the city; they take up a lot of space and can appear as hostile or neglected environments. Recent years of uncertainty have contributed further to this condition, but spaces for industry are undoubtedly more vital, fruitful, and colorful than the “brownfield” label that is often conveniently applied to them in anticipation of redevelopment.

London needs innovative ways to deliver more mixed, intensified, productive spaces. The Mayor of London, urban practitioners, local authorities, and industrial landowners are championing industrial intensification [4] key priority of the next London Plan. These ambitions should be quickly embraced and widely adopted in order to keep London a proudly productive city.

London Made, a film commissioned specially for the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism, celebrates the people, processes, and places that make London a productive city.

The exhibition looks behind the stage to explore the “back of house” supply chains of the Barbican, one of London’s most distinctive cultural venues. London Made follows a series of chains that lead out of the Barbican to uncover production activities and networks of supply that support and sustain the venue.

This exploration spans Greater London, uncovering layers of supply, from raw materials to final-stage installation and display. As well as cultural production processes such as set design, costume production, and audio-visual services, the chains featured in the film illustrate wider industrial activities, such as urban logistics, high-tech manufacturing, and food and drink production, which are crucial to keep the city thriving.

At the same time, this work looks beyond the current landscape to the policies, places, and pressures that shape how London works as a productive city. As the city strives to achieve good growth that benefits its citizens, how can those working in the built environment sustain and support London’s strengths as a productive city? London’s architects, urban designers, developers, planners, and policy makers are finding new ways of retaining and integrating industry in the city. Through a series of interviews, London Made draws on the city’s wealth of existing intelligence and expertise to explore what is being done, propositionally and strategically, to support London as a productive city.