The various built and open spaces constitutive of this project – an existing house, a new outbuilding containing an external room and sleeping areas, new wetlands and bird hide – sit within the area of Kullurk,[1] which was the local Indigenous Bunurong peoples’ own choice in 1840 for a reserve of land for their imagined future. A permanent water source is located there and early maps show that aboriginal routes cross through the area. Unfortunately, this wish was not granted. The various project’s interventions are spread out through a property of 100 acres that faces the Westernport coastal reserve and is connected to the Coolart Wetlands and Homestead as a result of a subdivision of the larger Coolart estate on the south eastern coast of Victoria just outside metropolitan Melbourne.

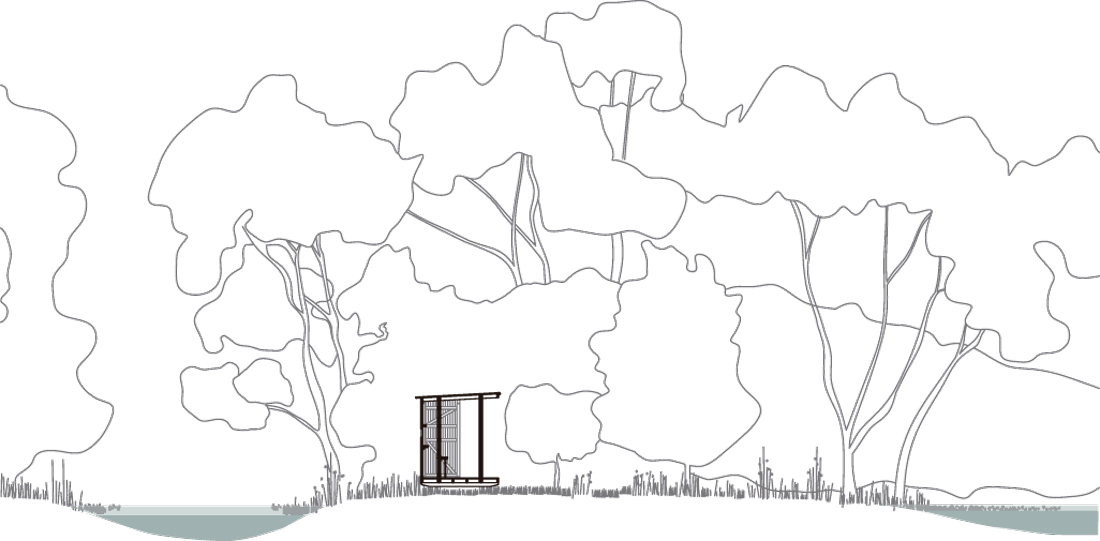

Outbuilding © Lucinda McLean

The project is an ongoing making of architecture, wetlands and regenerative farming, a nexus of natural systems and human movement adjacent to an intermittently closed and open lake lagoon.

Initially, when the project commenced, the property was a grazed farm and house paddocks with two dams. Now, seventeen acres of regenerating wetland is working in conjunction with the farmland and larger environment. In the standard sense of the architect’s commission, the project started as a conventional house addition, however, from the beginning it was understood that the project was more: the outdoor room which makes up half of the footprint of the new outbuilding is a space along a landscape path. Ten years later, a separate 2×2 metre bird hide structure was built in the regenerating wetlands, a ‘design-make’ project with RMIT Architecture students in collaboration with William Goodsir. This is a process that broadens the reach of this project

to an educational setting and the knowledge base of

future practitioners.

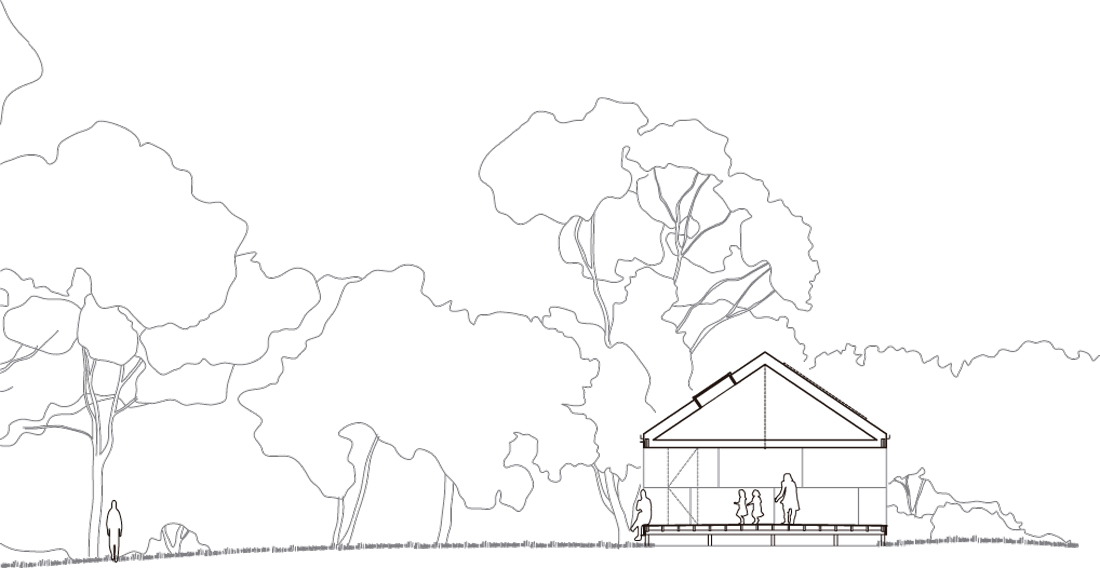

Outbuilding © Lucinda McLean

The project reinstates the changing and temporal qualities of swampland, an in-between condition, not solid, not liquid. Like a lot of the low-lying land around Westernport this land was channelised and drained to increase the extent of solid land that could be farmed. The pre-colonial conditions are not really known and even to attempt to replace them to its previous exact condition is to misunderstand this dynamic landscape as only one point in time. Instead, the landscape is ‘repaired’ by catalysing the context for repair through the stewardship of the site, and physically patching certain conditions to invite life in: by altering the ground contours from the narrow channel to broaden the movement and temporality of water and by ‘not doing’ as much as ‘doing’. For example, by allowing certain areas to retain water and connect to wetlands, dormant and translocated seed could germinate. After some years the owners noticed many ‘self-sown’ plants including Coastal Beard Heath (Leucopogon parviflorus) – this plant is extremely difficult to propagate as it needs to pass through the digestive system of birds.

There is now a chain of temporal water bodies linked to the permanent water body that supports this landscape to function as a part of and connected to, the wider, less disturbed one.

Wetlands © Lucinda McLean

Ground © Linda Tegg

The physical repair on this site is landscape based, where the architecture creates an occupation of the site that enables a close stewardship and points to the role of the private landowner. This strategy could also be described as catalytic. At the same time there has been consideration of this landscape and system repair in the decisions made around the outbuilding and bird hide. The new architectural structures work to create conditions for movement and intimacy through the siting of structure, seats, and shelves.

The bird hide embodies much of the project’s intentions. Designing a bird hide is a negotiation between human movement and bird systems. The siting of the hide is considered in relation to the macro scale of the bird and wind systems, with strong consideration to the flyways of migrating birds that arrive at this site. It is constructed using a minimal structure, so that noise and disruption are reduced while being built. Landscape here is not a broad panorama to be consumed as experienced in much contemporary coastal architecture. Rather, it is an intimate experience of being embedded within, with the rare experience of one’s existence being minimised in deference to what is being observed. The siting of a structure separate from the house creates a path of movement. The bird hide is a platform for stillness along the path, a place to be still, to be quiet, waiting to hear, to observe. The seats of the bird hide are configured to allow for people to face outwards,

or face inwards together.

How we engage with the natural environment changes how we value it.