Intensive globalization has been the order of the day in the United Arab Emirates in recent years. Boris Brorman Jensen focuses on architectural developments in two of the Emirates with the question “Is there a locally distinct architecture, or is it subject to the spirit of the global market?”

Dubais’s striking skyscraper corridor along Sheikh Zayed Road in morning mist. The city-state in the United Arab Emirates has seen huge growth since the beginning of the millennium. Less than four decades ago this area was by and large uninhabited desert.

The so-called Arab Spring that has spread from Tunisia, Egypt and Libya to large parts of the Arab world may not be an expression of any ‘spring ’ in a political sense. But although the democratic hopes that were sparked in December 2010 seem at the time of writing to have been superseded by growing despondency and pessimism, it is still hard to imagine the developments rolled back. The events have shifted some demarcation lines. Occupations of central squares, mass processions and street fighting have left us with a picture of an awoken political public sphere. With social media such as Facebook, Youtube and Twitter the stifled criticism of former times has gone viral. The rebels’ mobilization and the use of social media as autonomous command posts have redefined the space of political action and created a new framework for individual activism. The Arab world has seen an alternative public sphere grow up that is hard to control through state censorship, and the traditionally separated and hermetically isolated private sphere has been opened up.

The resulting shift in the established dividing-lines among social, cultural and political spaces can be read directly out of the current art in the region, where a new generation of artists seems preoccupied with scanning the new fronts and exploring the potential in the use of the new communication technologies. Yet it is still an open question what the so-called Arab Spring will mean for architecture in the region.

Architecture is a bound, relatively conservative art form and although it may be an unreliable sign, ‘free’ art often functions as a forewarning of the changes that architecture will later undergo. As a function of political and cultural norms, Arab architecture has been characterized by clear divisions between private and public space, but there are good reasons to expect that the changes outlined above between the public and private spheres will in the longer term also be reflected in the architecture. Developments can go in many directions, and the present developments do not yet paint any clear picture.

When one looks at the individual states in the region, very different situations emerge. In Egypt the upheavals on Tahrir Square in Cairo have led to a certain responsiveness and a turbulent reform process, while the revolt in Bahrain has been brutally crushed with more oppression and the consolidation of the dominant power structure as a result. Nor do the country’s rich neighbors, Abu Dhabi and Dubai – the leading countries in the United Arab Emirates and the subjects of the following – seem to be affected by the uprisings around them.

Both countries deny any suggestion of crisis and have invested massively in the development of a profitable tourist industry. They have long been working to appear relatively liberal, but despite ongoing criticism from human rights groups and external NGOs the ruling circles still operate undisturbed within their own territory, and their power is legitimized exclusively by decrees that are beyond discussion, and by charismatic self-staging.[1] Ostensibly, everything is always under absolute control. Domination is rooted in a perfect, static bastion that contrasts starkly with the dramatic development in urban and architectural space over the past three decades. Instead, constant hyper-growth is seen as an expression of power’s excellent capacity for dynamic self-perfection.

Pearl Square in Manama, the capital of Bahrain, was at the centre of a budding rebellion which was quashed with an iron fist. Even the physical urban space has been eradicated. The three satellite pictures were taken in January, March and May 2010 respectively.

This political/cultural paradox is underscored by an externally originating, authenticity-seeking cultural critique which maintains that the many radical development plans and spectacular construction projects taking place in the two Emirates have nothing to do with Arab culture and exist in another reality than the Arab one.

There is something of science fiction or SimCity about Dubai. You can’t see it if you don’t happen to know about it, but the gigantic structure on the left in the picture and the huge pool form Dubai’s most prominent urban space.

The two Emirates have undeniably undergone rapid globalization over the past couple of decades, and the physical environment seems almost to have been ‘SimCitified’ by the homogenizing power of the worldwide machinery of speculation. This is expressed by an architecture that does not relate to physical context and site-specificity, but looks the same everywhere on the planet. The large, more or less state- run contracting companies that operate in Dubai and Abu Dhabi have been successful in exporting their ideas to countries both within and outside the region. Global imports/exports are probably not what architects with an interest in cultivating and developing regional distinctiveness primarily have in mind. But the unlimited exchanges of formal idioms are nevertheless a new market condition for architecture, one to which very many architectural offices all over the world must adapt. Architecture has, for better or for worse, become an export commodity, and the images and cultural symbols that globalization has sent into orbit affect even the smallest of small towns. It is not uncommon for architectural ‘copies’ to be built before their originals. The global building industry can go ahead and ‘print’ any architectural rendering anywhere in the world. With or without the participation of the architect.

But at the same time globalization has also proved capable of promoting a local cultivation of differences.

Dubai and Abu Dhabi have often been stigmatized as antitheses or fake representations of ‘the Arab’. The problem with this is that it partly dismantles the illusion that the Arab societies would be able to set more of their rich culture free if paths were opened up for more political and cultural exchanges.

And as a corollary, if Dubai and Abu Dhabi are truly to be considered Arab exceptions subject to cultural hyper- inflation or runaway private enterprise without roots in the region – then it seems unfruitful entirely to set aside the critical reflections to which the developments in the two Emirates give rise. The architecture in Dubai and Abu Dhabi offers very little evidence of the depth of Arab cultural history, but despite everything the two Emirates have been the region’s biggest construction sites for many years now, and there is no reason to wholly dismiss the phenomena that are emerging on the cultural surface.

The Louisiana’s exhibition New Nordic – architecture and identity in 2012 revolved around the Nordic architects’ attempts to develop, reinterpret and reform public buildings, institutions and spaces.

A guiding principle in the exhibition was the question of architecture’s relationship with the context and the Nordic architects’ exploration of the building traditions, materials and climate of the local area; a particular sensibility that the Norwegian architectural historian Christian Norberg- Schulz summed up in the concept ‘Genius Loci’ – the idea of the presence of a ‘spirit of the place’ in architecture.[2]

As an extension of this it is interesting to ask the following questions: How does the absence of a bourgeois public sphere[3] come to expression in the architecture of the two Emirates, and what institution- al role does architecture play in the all-encompassing one- dimensional space, private and political, of these countries? Is there a local specificity – or has Genius Loci become ‘Genius Logo’ – architecture entirely subordinated to the spirit of global marketing?[4]

What role does it play that most of the construction in the two Emirates is designed by architects from the outside, and what ideals do they try to represent?

From Public to Published Space

It is hard to imagine the built environment in the two rich Emirates undergoing a transformation as a result of popular protests under the present regime. Neither Dubai nor Abu Dhabi has in reality any kind of political public sphere. The turbocharged development in the two Emirates seems to have accelerated the clan- and tribe- governed social system from a premodern feudal state directly into a globalized era. There are lots of symbols of power and of the economic elite around on streets and squares, but the physical space has been completely cleared of counter- cultures. Strictly speaking it is meaningless to speak at all of a ‘public sphere’ in the traditional sense. The concept quite simply has no constitutional precedent, since the state is by definition private property. Up to 90% of what one in everyday language calls ‘the population’ in the two Emirates consists of foreign workers on temporary stays without any kind of political rights. Only a small minority of the 10% who are ‘national citizens’ owns all the land, and there is no space that in principle belongs to everyone. All land and property is in private hands and is either ‘gated’ or commercially operated. The classic distinction between private and public is a vital antithesis in architectural thinking, but this central element in modern urban planning makes no difference whatsoever to the private utopias that drive development in the Emirates. The absence of true public space means that one must instead try to distinguish between private space and on the one hand what could be called published space on the other. Private spaces are characteristically places and spaces that are either gated communities or otherwise inaccessible to outsiders. Published spaces can be defined as images of private property that are openly circulated in various media. Private spaces are always more or less discreet and protected.

The Emirates have several neighborhoods of gated communities where no outsider can enter without an invitation. Large parts of the most spectacular projects are also closed areas and private spaces, for example the artificial island group The World, the skyscraper Burj Khalifa, the tallest building in the world, and all the branches of the artificial palm peninsulas Palm Jumeirah and Palm Jebel Ali. The entrenchment of the private permeates urban space as in many other Arab cities, but the formal idiom and ornamentation of the boundaries are marked otherwise than in the traditional urban milieu that one finds elsewhere in the region. The classic element of Arab architecture, the mashrabiya, which lets the observer look out without being seen, is a rare sight in the modern air-conditioned buildings of the Emirates. The filigree pattern of the mashrabiya ornamentation, which characterizes the historical architecture of the region, has been replaced by screening construction components, especially mirror glass, which means that the individual expression of the street space is entirely dissolved in some places. The modern facade screening negates the social radar that functions in Nordic urban space but at the same time, in particularly successful cases, it creates fascinating reflective spaces that replace uncontrolled in- sight with the phantasmagorically eye-catching.

The virtual opposite of private space – published space – may be trademark-protected, but on the whole is always on display and more or less strategically exposed outside its own property boundary. The architecture of ‘published space’ is not formed by the distinctions and transitions between public and private spaces. It is governed by different architectural concepts based on one of two different contextual views: either total local subjection to the client; or a distanced political agnosticism.

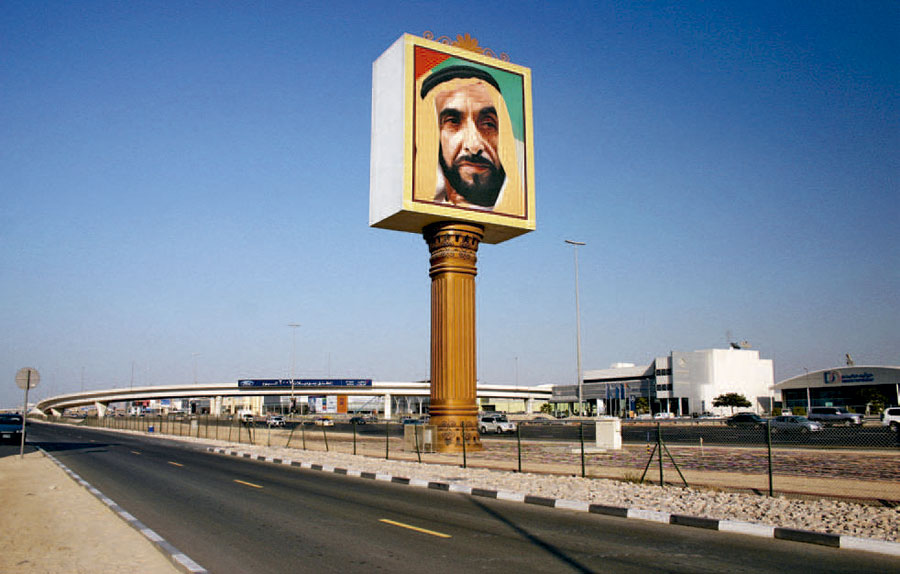

Political space in the UAE is entirely one-dimensional. The prevailing aesthetic diversity does not apply to political representation. Here we see the charismatic leader, former President Sheikh Zayed, in an elevated pose by a motorway exit.

Most private utopias in Dubai are literally introverted; they turn their backs on the surroundings to protect their inner worlds. Most of the residential projects are either gated or surrounded by a ring wall, like this entrenched residential enclave not far from the Mall of the Emirates at Sheikh Zayed Road.

The modernist architects played with the idea of a curtain-wall of translucent glass. The generic architecture in the Emirates screens o% from the sun and the outside gaze. The classic ‘curtain wall’ facades of the skyscraper architecture, as here on the Dubai skyline, have been given a ‘Ray-Ban’ attitude.

Dubai’s “Geoglyphs” seen from Google Earth. The three palms and the property development adventure ‘The World’ were hard hit by the international financial crisis and remain partly unfinished. Nevertheless they have set new standards for the branding of cities. The phenomenon spread quickly to other countries in the region including Bahrain and Qatar.

Sheikh Zayed Road forms a kind of arrival portal and principal stage set for Dubai’s symbolic space. Here we find the biggest concentration of the most spectacular skyscrapers. Viewed from the right angle, an impressive sight – but 150 metres from the prominent linear-perspective view the set collapses like a Potemkin corridor.

Sheikh Zayed Road seen from the Dubai Metro. There is not much life between the houses out along the eight-lane motorway, but from inside the air-conditioned first-class cabin the almost unbridgeable distances of the desert city become an experience like a Fritz Lang movie.

There are many different types and varieties of published space. The biggest and best known are globally marketed corporate brands that gather a variety of business strategies in a physical design, for example the architect Jon Jerde’s Dubai Festival City. The most conspicuous examples of the type appear in the form of giant symbols in Google Earth – but without the ‘street view’ option. Published space often appears as clusters of ‘bottle architecture’ separated by artificial irrigation and boiling asphalt with no visible signs of life between the buildings. The best example is probably Sheikh Zayed Road in Dubai. Other types are more ethereal and behave rather like mirages: a highly published skyline with no solid base, which disappears and dissolves like a spatial illusion when one approaches; various aircraft-landing and motorway scenarios oriented towards focal points for financial power, but without identifiable spatial qualities outside the mediated ‘experience cabin’; the city reduced to a series of Kodak Moments and Skytrain aesthetics. Other types of published space are more alluring and exuberant, like the evening show in front of Burj Khalifa. Some are more or less Paradise-like tableaux of glossy worlds created as a consumption context for the absolute elite, for example the Burj Al Arab Hotel – exclusive by virtue of their inaccessibility for the man in the street.

There are of course parks where as a rule you can get in if you pay admission. It is also possible to get on to the beach in several places without a ticket. But these relatively free activity spaces lie as isolated islands in a sea of commercial business areas and private fortifications.

It can be hard to tell whether a published space you have seen in print also exists in reality. Computer renderings and other edited reality are in fierce competition with the realities in this game. But deepest down it does not matter, for published space is a catalogue item, and in the end far more of it is produced than the world has room for. Published space supplants the common good and replaces it with a latent world of computer animations – an eternally expanding space of desires and fantasies. It is a spatial concept related to the theme park, whose only mission is to capitalize on its architectural illusions. The architecture of published space works through its strong illusory power, and many of the best designed examples, such as the well equipped shopping malls and the modern traffic systems hum with activity and give the impression of diversity and public life. Published space compensates to a certain extent for the absence of public space, and may feature elements of symbolic altruism: a captivating sculpture in a beautiful roundabout or kilometers of imaginative motorway decoration. But published space never offers its owner any resistance, has no collective memory, requires no consciousness of tradition and in principle is entirely detached from time and space. The architecture of published space not only produces images of ‘the new’, like the fashion industry; it has also embarked on the fictionalization of the past. The newly built neighborhood Al Bastakiya in Dubai is a good example of how the stage design of published space can negate chronology and offer all possible styles: past, present and future architecture at one and the same time. The architecture of published space has exclusively pecuniary obligations and in principle can expand its formal universe endlessly. It thus forms the substrate for a new architecture of frivolity, released from limiting social considerations and civic burdens, quite free to develop new technological solutions, programmatic concepts and aesthetic expression which may (or may not) be traceable back to a more committed political/cultural context. The tautological expressiveness [5] of this architecture of frivolity perhaps leads to a general strengthening of architecture as form and style. But the question is whether the runaway formalism in the two Emirates will ever contribute to the resolution of some of the issues that the future population of the region will have to address.

A Path between Caricature and Sensationalism?

Most architectural theorists agree that it takes more than a client with a yen to invest to turn construction into architecture. Even a very strong desire to invest does not automatically lead to great architecture. Some bearing idea, cultural ambition or conscious experiment should be in play. Manic construction activity is not an architectural goal in itself, and in this connection many attempts have been made to understand the qualitative specificity of the two Emirates’ particularly expansive urban development strategies and more or less conscious planning and architectural policies. [6] Most accounts drawn up by various practicing architects, architectural writers and cultural observers fall roughly speaking into three main groups: the sensational report, the caricature and the heroic chronology. The last of these is the most widespread and typically periodizes development into four stages: (1) a static petty trading and pearl-fishing society (until the 1950s) in a ‘cradle of the nation’ at the edge of undeveloped desert which (2) with British engineering assistance (1950s-1971) is able to develop an elementary infrastructure; (3) the discovery of oil and the creation of the independent Emirate (from 1971 until the early 21st century), which slowly and steadily develops contours with the aid of heroic visions (realized from the beginning of the 2000s on), and despite the international financial crisis has been enhanced into a global reservation for the development of so-called ‘starchitecture’.

The Atrium in the 321-metre tall luxury hotel Burj Al Arab in Dubai. The hotel was the first project to move out to its own island in the water o3 the coast and in many ways was the precursor of the later geoglyph projects such as the Palms and The World. Burj Al Arab was at the same time the ruling Mactoum family’s claim to fame and financial dynamo.

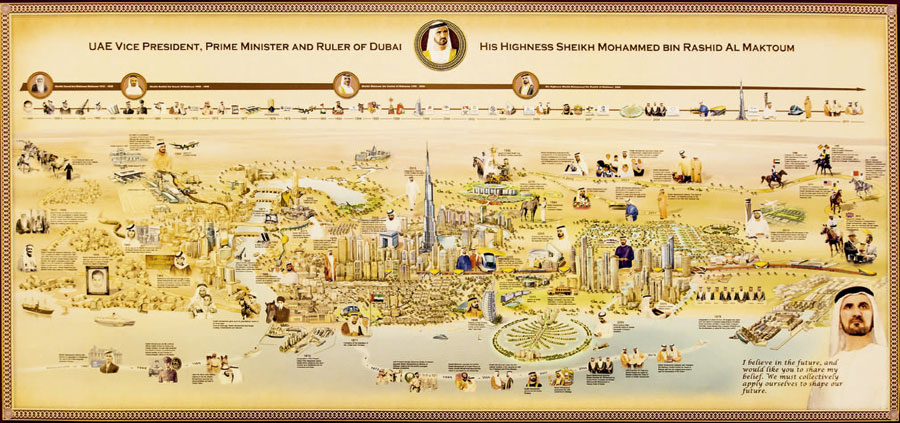

An official version of “The Heroic Chronology”, exhibited in the Dubai Mall.

Each phase has its myths and narratives about challenges and triumphs. However, the overall national epic, including the latest, My Vision: Challenges in the Race for Excellence, by the Emir and Prime Minister of Dubai, Vice President of the United Arab Emirates, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Mactoum, provides only one theme of architectural history, where all the measures taken, even the least significant, become symbols of the official self-understanding based on one long national-romantic epic. The heroic chronology is often narrated in images taken with a long-distance lens where the architectural history is reduced to a linear royal succession of motorway and construction projects, all documented and dated by series of satellite and aerial photos from the past forty years. This one-sided account of development makes sense in a context where power is inherited and is not challenged, but does not seem particularly interesting when the architectural development of the Emirates is viewed in a wider context. The monomaniac architectural history of enduring love for the young, dynamic nation has no dialectical oppositions and must therefore rely on the chronology of the works.

The heroic chronology’s blind bedazzlement with the building boom has much in common with both the sensational report and the caricature. In principle they all reach the same conclusion, but on opposite premises. The Emirates are expounded by all as a fantastical ‘Amokland’ where the architecture can be regarded as an advanced form of ‘water globe souvenir’ that the architect can take on further business trips and exhibit at a website. The sensational report envisages a gigantic EXPO without restrictions from a surrounding civil society; a dreamland full of customers and clients on investment-driven hunts for the iconic aura of the architecture of the frivolous – the locus of inconceivable possibilities where the architects of the world can concentrate on working up the most imaginative illustrations of the current business plans. The interpretation of the sensational report is positive and views this as a great emancipation for architecture. Gone are all the social and cultural impositions, the scruples about authenticity, the burdens of tradition and contextual considerations. In this ‘exceptional logic’ architectural feats can be judged on the degree of luxury or ranked by size as in the Guinness Book of Records. [7]

The criteria of success for the architectural sensations are literally in private hands, and all formal value judgments are reduced to a lower order of subjective preferences. Like w or dislike t. A consistent meta-thesis in the many sensational reports is that the Arab world, with Dubai and Abu Dhabi at its head, has gone fully in for the development of ‘The International Style’;[8] that the region at present occupies a leading position in the worldwide skyscraper race; and that ‘Arabia’, through cultural appropriation of the archaic typologies of modernity, is now actively contributing to architecture’s global evolution; and even though in many people’s eyes there are far more bad than good examples to point to, and even though the experiment at present does not seem to be strengthening the region’s own architectural development – for example by developing a sustainable, present-day vernacular (native) architecture) – the sensational report does have a point. The further development of the International Style in Arab cultural space completes a cycle which has in many ways been over- looked. The architecture of the modernist breakthrough was clearly inspired by North African and Arab architecture. So were the Nordic regionalists, not least Utzon. So in that light the idea of stealing the International Style back seems very attractive. The weakness in the sensational report’s implicit analysis, however, is a lack of interest in critical discourses.

The sensational report’s opposite number, the caricature, does not lack a sense of criticism. Most representatives of this genre are comic tales of lost worlds or rather cultural clearance sales in what has been called Dreamworlds of Neoliberalism, [9] which describe the architecture in Dubai as a nightmare from the past in which Albert Speer meets Walt Disney. [10] The historian Mike Davis and other indignant writers argue that architecture must be able to face political criticism at any time, and that ‘context’ also includes the political climate. In their eyes ‘Project Dubai’ has gone off the rails in terms of the environment, human rights and for that matter urban planning. Davis’s critique is relevant and topical, but the problem with seeing developments in the two Emirates exclusively as political parodies is that the critique keeps back anything resembling constructive architectural criticism. The built-in irony of the caricatures offers no sustenance to much more than boycotts on the one hand, and on the other hand even more cynicism from the expatriate architects who will build come what may. As an architect one can of course choose to stay away from the Emirates; but that only precludes the possibility of influencing developments through active intervention. In other words one should find a path out of this, somewhere between the absolute contempt of the caricature and the bedazzled gawping of the sensational report.

Trojan Horses or Monuments to Repressive Tolerance?

In 1995, the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, who has in several contexts discussed the turbocharged developments in the UAE and the other Gulf States, published an essay on Singapore, which in many respects represents a precedent and an interesting basis of comparison for what is happening at present in Dubai and Abu Dhabi. Koolhaas remarked at the time that what we perceive as Western has become a universal ideal, on which we in the West no longer hold a patent.

So what Singapore’s architecture underwent was not westernization, but modernization. [11]

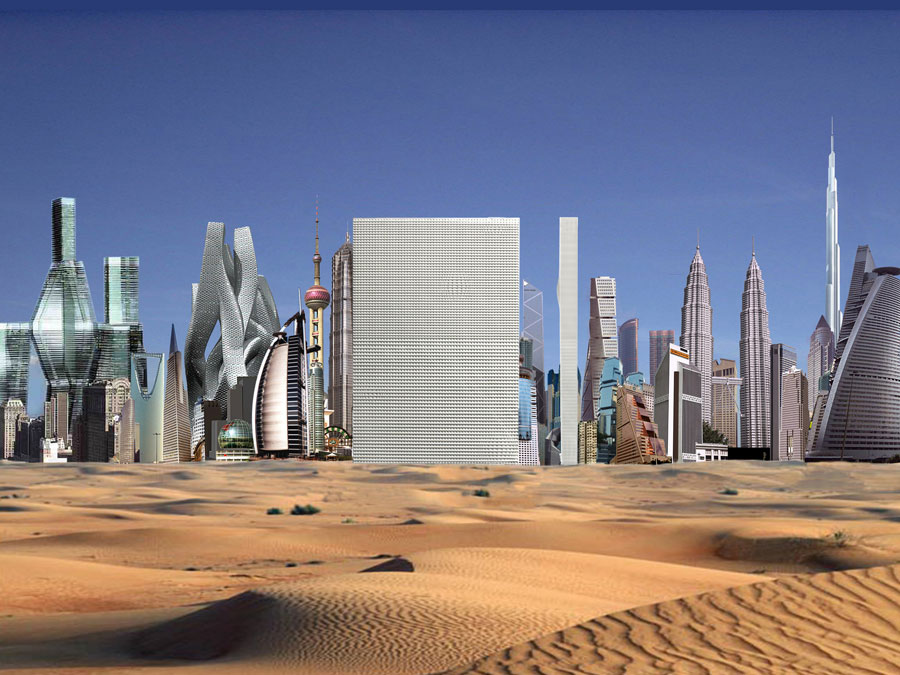

Dubai Renaissance by OMA, Dubai, 2006.

Waterfront City by OMA, Dubai, 2008.

Koolhaas’ attempt to understand and challenge the inherent logic of the Gulf States’ architectural and urban development has nourished a couple of interesting projects with different approaches to what one could call projective criticism. The strategy can be paralleled with the Danish visual artist Asger Jorn’s over- painted hotel-art pictures. In the same way as Jorn shook up the ‘naturalized idyll’ of the genre painting or turned it inside out, in several of its projects Koolhaas’ office OMA has installed what may be likened to Jorn’s A Disturbing Duck, [12] for example in the form of the Star Wars Deathstar in the Waterfront City project in Dubai. [13] The project was not an endgame for the Dubai Space Opera, but it launched a discussion of the ongoing architectural ‘star wars’ and the attempt to create a world-class city with the aid of iconic buildings. Another good example is their Dubai Renaissance project from 2006. The 200-metre long and 300-metre tall modernist monolith represents a direct criticism of the trinity in the Emirates’ architectural credo: thematization, iconic desire and idolatry. Mixed in with the clear statement there is at the same time a layer of critical connotations. Part of the national mythology is the tenacious anecdote of how the Emirates, after 11 September 2001, have been able to deflect anger against the western world and sublimate it into a potent Islamic creative force.

Waterfront City by OMA, Dubai, 2008.

Dubai Renaissance by OMA, Dubai, 2006.

If one studies the details of the facade expression of the OMA project, other more diabolical undertones emerge. It is claimed in several quarters [14] that the logistical network behind al- Qaeda operates through the UAE, and it is hard not to see the building as a death mask of the World Trade Center. The project is unlikely to topple its own client, but it is still able to suggest the con- tours of a Janus-head in the official profile of the regime.

Subversive aesthetics are effective within the world of art, and have made their appearance in earnest in Abu Dhabi. On a partly artificial island close to the existing centre, nothing less will be built than one Guggenheim Museum by Frank Gehry, one Louvre by Jean Nouvel, one National Museum by Norman Foster, one Performing Arts Center by Zaha Hadid and one Maritime Museum by Tadao Ando. It will be exciting to see whether the European and American cultural mastodons with their whole content of feminist art, nudity, homosexuality, political critique and other emancipatory creativity will become Trojan Horses or monuments to repressive tolerance.