Some drawings are made with the same sense of purpose of writing: they are notes we take. Others try to resolve the execution of one project in one particular image or imagine how it would work. There is a third type that is produced after them—that type of drawings made a posteriori, once the work has been built—able to raise a new approach to the project. All of these types of drawings make possible a systematic approach to the work, even if they force their internal logic up to its absurdity.— Bruce Nauman, Drawing & Graphics (1991)

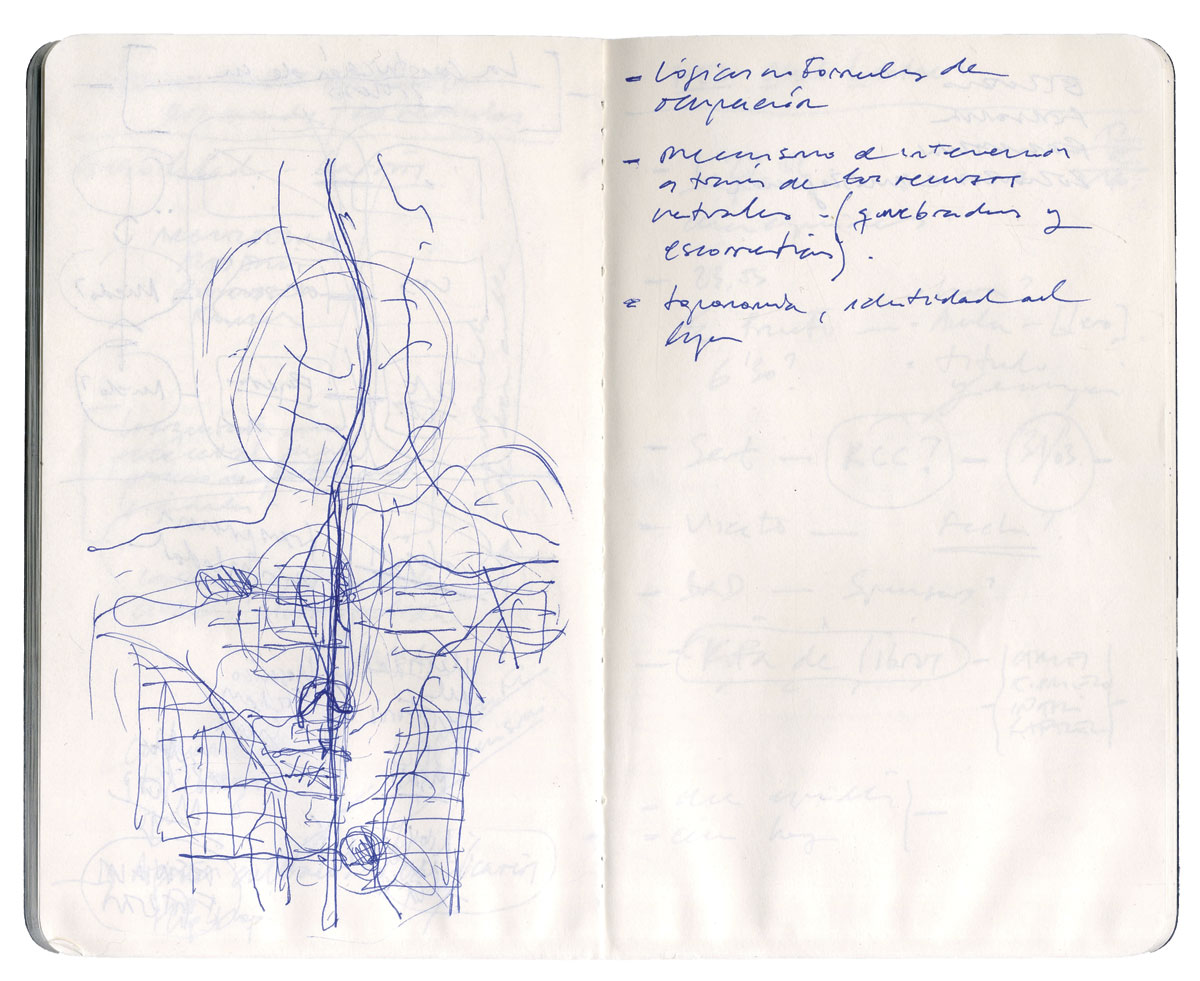

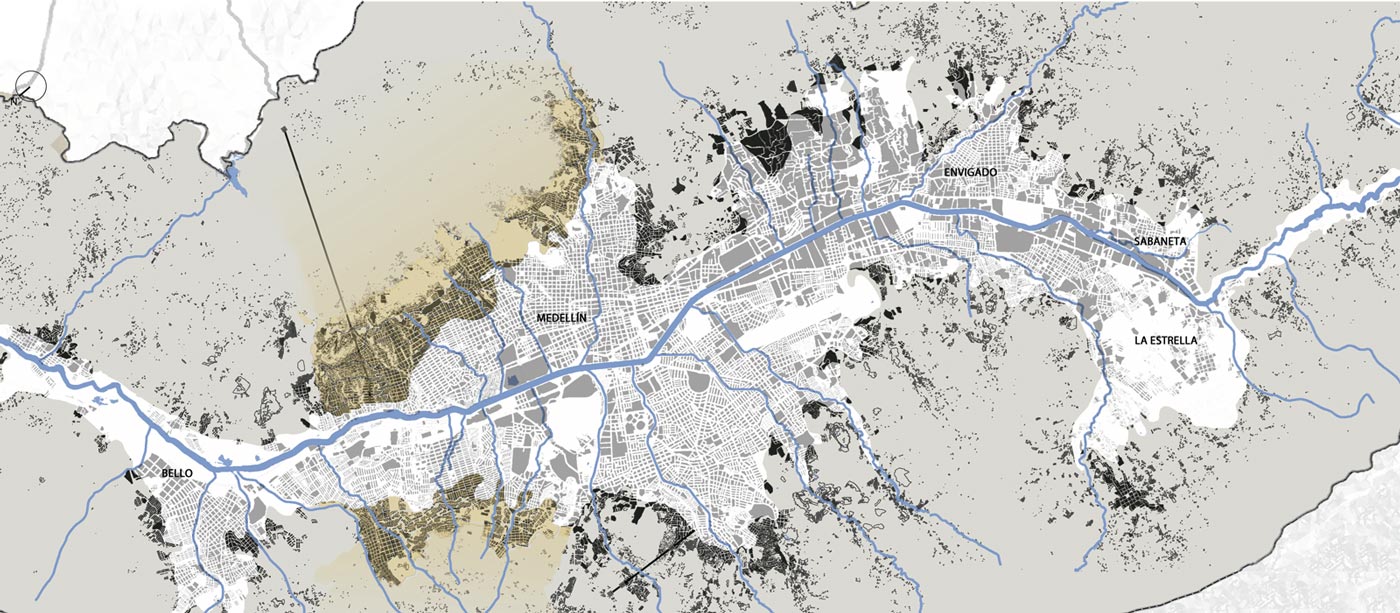

During a recent encounter with Colombian architect Alejandro Echeverri, I asked him to draw a plan of his city, Medellín, in one of the blank pages of my notebook. It was an exercise in synthesis and memory. Echeverri describes his work in Medellín not in terms of isolated architectural episodes, but as the construction of a narrative that exposes the underlying forces that fostered violence and the resulting transformations of the city.

Alejandro Valdivieso Only 25 years ago, Medellín, Colombia, was one of the most dangerous cities in the world. Today, largely thanks to your work, it is considered a case study for inclusion and social innovation processes. Fear, in this instance, is not understood as an abstract emotion or hindrance, but as a driver of positive action.

Alejandro Echeverri In Medellín, fear defined our reality; it displaced our intellectual interests—and for that matter our agenda as architects—and linked us emotionally and physically, in a very intense way, to the places where we were working. Violence engenders fear; it is a provocation; it asks you to change your architectural roadmap, to make visible the struggle and the tragedy.

AV I want to look more closely at Medellín’s history by comparing two images. The first is an interior photograph taken in 1949 of Josep Lluís Sert’s house at Lattingtown Harbor Estates in New York. In the photo, you can see his masterplan for Medellín hanging on the wall. The second is a photograph of Medellín itself, showing one of its hillside communities torn apart by violence. There is a 50- year gap between these two images. When juxtaposed, important paradoxes arise. In the Sert image, we see the principles of CIAM and the translation of the European modernist agenda to the American continent. In the other photograph, we witness the social reality that emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s in Latin American cities like Medellín. The image of Sert’s house conveys a placid petty-bourgeois condition where the Latin American city appears as a piece of art—an abstraction, an element to be exhibited with a dose of political and intellectual correctness. The image of Medellín shows the opposite: violence, destruction, control, and other underlying forces that condition the spatial processes within cities, yet are largely alien to the design professions. In what ways can we relate these images?

AE These images express the contradictions that arise when you confront two very different realities. The image of Sert’s house insists on the colonial gaze over Latin America. It does not clearly express what being and living in a place means. The transformation of the concept of “space as object” to “space as place” means understanding space as action—spatializing social life, politics, and other vectors. It also means understanding the gap between action and concept.

AV Did the work of Sert and Paul Lester Wiener in Colombia, or of other architects in Latin American cities during that period, contribute to a better understanding of the conditions and lifestyles of the inhabitants?

AE Although projects like the ones by Sert and Wiener made between 1947 and 1953 made visible some of the realities and idiosyncrasies of these territories and influenced our approach to the city, they failed to take into account certain factors that linked space to social and political forces. But Colombian and Latin American cities become rich case studies that contributed to reshaping the theoretical agenda in urbanism. For example, a plan of Medellín appeared on the cover of L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui in 1951. Their work helped our cities to gain visibility, which was a major step.

Josep Lluís Sert, Sert House, interior, Locust Valley, Long Island, 1949.

AV There is a risk in discussing the notion of fear and violence, especially in relation to so-called developing countries. Many North American architecture schools are being flooded with a social agenda that is cynically transforming notions like “fear” or “violence” into slogans in the service of an exchange value rather than a use value. The bigger question is how the architect participates in the management of urban processes. What should the attitude of the architect be in relation to the cities he or she inhabits?

AE A whole generation of Colombian architects, urbanists, and designers is truly committed to and engaged with a new political reality. I worked closely with Sergio Fajardo, who was committed to the idea of making politics from a social and civic perspective. He launched a movement that brought together professors and scholars, entrepreneurs and businessman, social and communitarian leaders, and cultural agents. Later, in 2004, Fajardo became mayor; after him, in 2008, the coleader of the movement, journalist and writer Alonso Salazar became mayor. Salazar’s 1990 book No Nacimos Pa’ Semilla allowed us to listen to other dialogues that represented the violent reality of the comunas. It is in the question of how to transform this reality that we can find some of the roots of what has been called “social urbanism.”

I am not a politician or a writer; I am an architect. I was educated as an architect and I try to understand the city through architecture. The transformation of Medellín has sensitized and engaged a dynamic group of young architects. They studied during a period of extreme violence, social segregation, and inequality, and are largely responsible for the way in which architecture is being redefined, based on the experience gained in the university, doing public competitions, and working for the government.

AV From 1998 to 2011 you lived in Barcelona, working on your doctoral studies at the Laboratori d’Urbanisme within Escola Tècnica Superior d’Arquitectura de Barcelona. What did you learn in Barcelona? Do you see any concrete connections between the research and teaching you did there with Manuel de Solà-Morales or Joan Busquets and your later work in Medellín?

AE I went to Barcelona to think about Medellín. Not because of the parallels that may exist between the two cities— actually, there are not many—but because of more subtle connections, like the fact that are both the “second” cities of their respective countries. In conscious and unconscious ways, they have both maintained a distance from the political, social, and economic power that a centralized state often gives to the capital city. I went to Barcelona to find working tools within the university that could be applied in Medellín. To find tools that would help us use the architectural design processes to change the reality of the city on a theoretical basis.

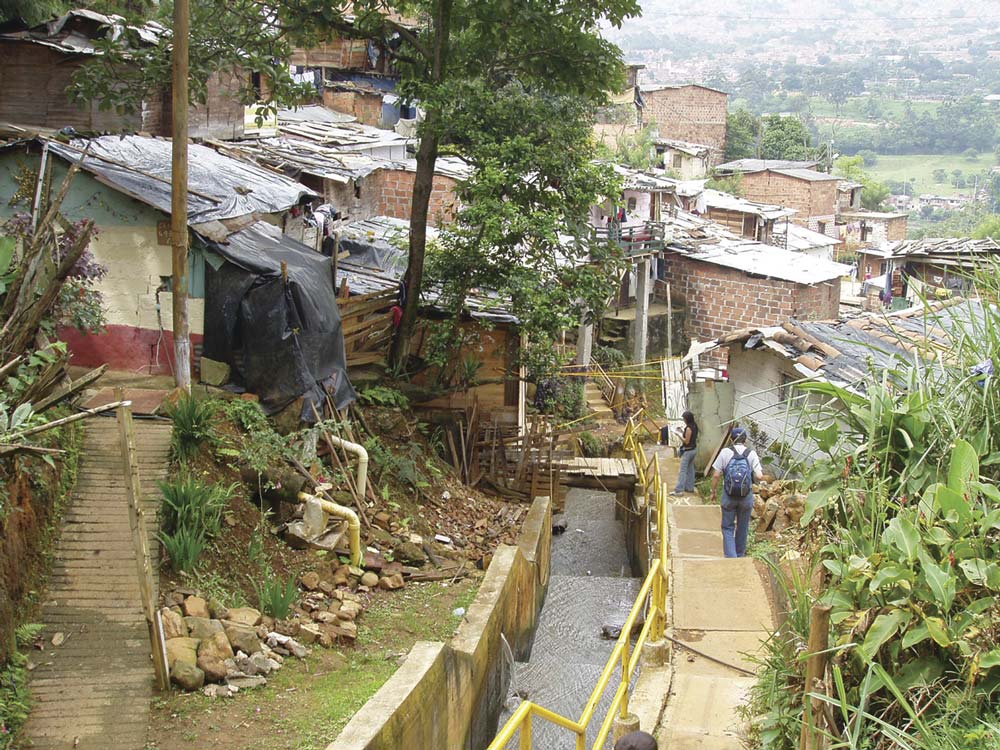

Quebrada Juan Bobo running through a barrio, Medellín, 2008.

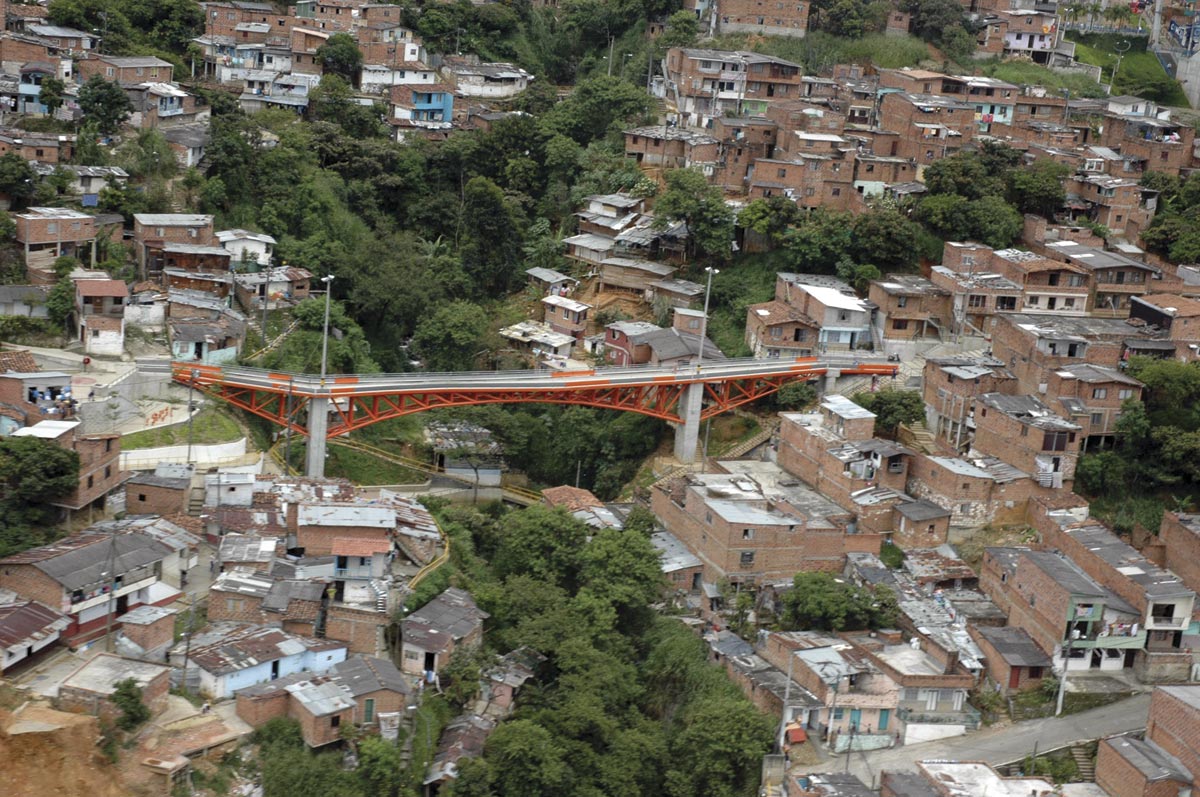

Alejandro Echeverri Arquitectos, bridge in La Herrera, Medellín, part of the Integral Nororiental urban plan, 2006.

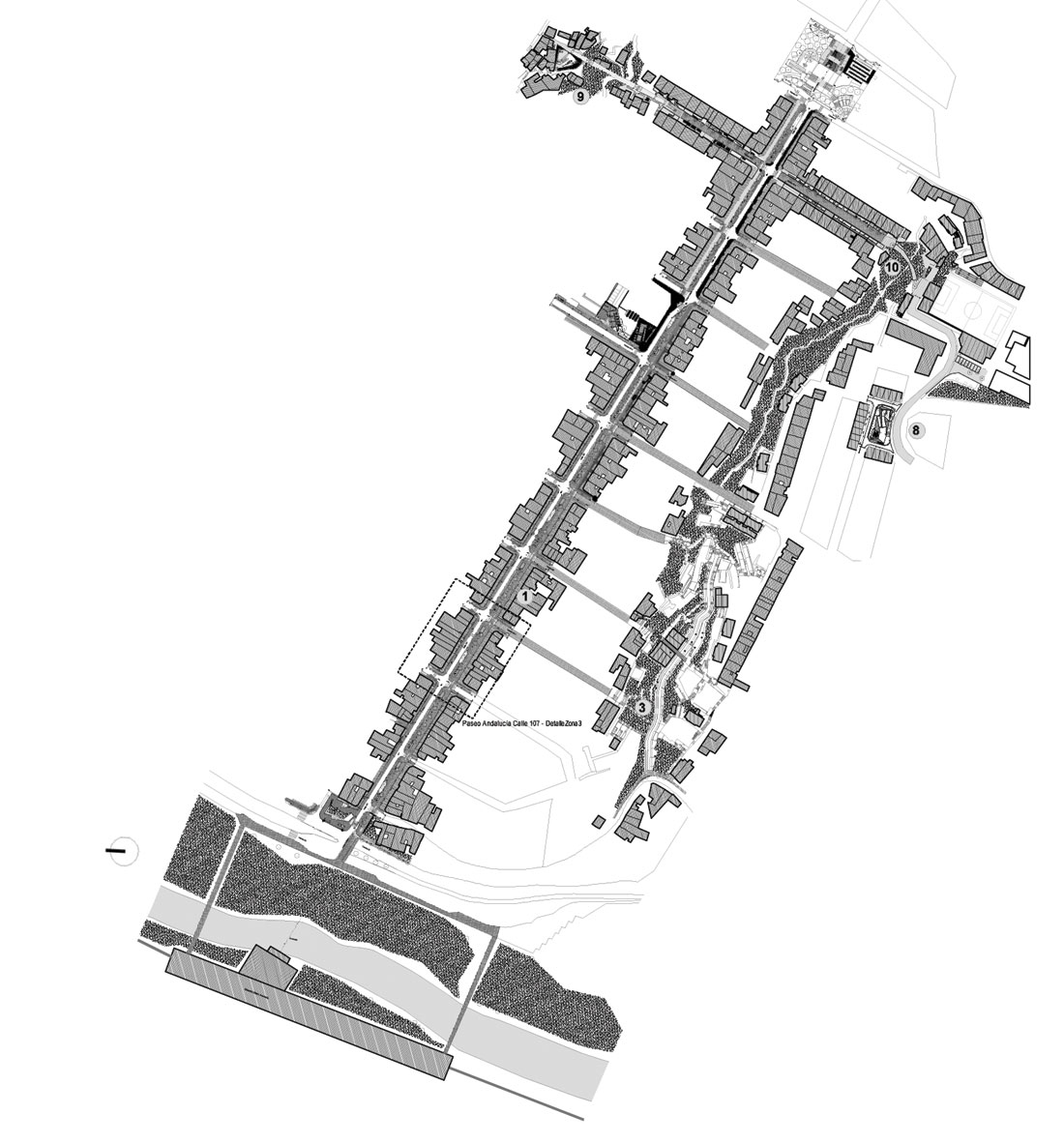

When we talk about how to draw Medellín, we are really talking about how to think about and analyze the city, how to unfold both the visible and underlying forces that shape it today. The act of making cartographies for the city has to be adapted to many variables. Remember Solà-Morales’s words on the culture of description: “Is it possible to draw a country? What would be the architectural expression of a territory?”

Within the university, it was possible to produce a new “drawing” for Medellín. The university became the perfect platform from which to ensure convergence between different narratives, to find practical answers to extreme situations. Education enabled us to elaborate analysis in connection to real actions.

Medellín

AV What is the connection between the university and the streets, or the barrios? How have you worked with public space?

AE The street is not only a spatial condition; the street is action. The space of the street shapes meanings and identities. We must think about spatiality rather than space. The street allows us, the architects, to work within the scale of urban action in order to shape a narrative across small daily and ordinary actions. But the street is also an urban element that is strongly connected with social control mechanisms. Violence and fear are invisible forces that are revealed in the built space of the street.

From 1983 to 2000, militias ruled the streets of Medellín. The absence of social activity, of life, of overlapping uses in time and space led to an atmosphere of apprehension. But public space helps to induce social relations and human contact. This involves redefining the idea of street and trying to understand it as a design mechanism, an architectural device that introduces proximity and ordinary interactions between people. The street has to be an effective tool. It becomes a device that links the smaller scale with a bigger morphological scale in territories characterized by informality, exclusion, inequality, and instability. Working in the streets means engendering actions that start to make visible a bigger narrative.

Nor Oriental Integral urban plan, 2008.

Medellín masterplan, 2008.

AV What about the “other streets” of Medellín—the quebradas, or natural waterways that run through the city, segregating it more profoundly, and contributing to violence and fear. The sinuous routes of the quebradas emerge from the unique geographical condition of the territory. You have insisted that the streams—which you sketched with such intensity—are important to consider when we analyze Medellín. How do you understand the streams? How does geography contribute to segregation in the city? Is there a direct relation between the streams and violence?

AE Understanding the quebradas involves a strategy that uses geography and orography on an operational basis. It is a way of “reading” the city, but also of taking action on that “other city”—the city of informality and illegality, of precarious urbanization standards; the city that lacks social structures for education, employment, and spatial organization. Fear and violence arise in places where education is absent. Architecture and spatial politics have to deal with this.

In Medellín there is a disturbing discontinuity between the urban fabric of the city and the natural fabric of the streams. The social fabric has contributed to the discontinuity two realities, two cities, which echoes the one manifested in the two images we compared earlier. Medellín has to address the friction between the streets and the streams. We can see this friction in the plans of the city, those that clearly show the occupancy classes, for example. The friction between the city and the mountains has generated conflict situations that need to be understood as opportunities. The streams used to be the frontier that defined the struggles between the militias, for example. Architecture has been working to build connections—physical connections, but also social interactions among citizens—in order to write a common narrative against fear.