The bulk of urban space that makes up contemporary cities was built during the 20th century, especially in the second half. One characteristic of cities is that their creation and existence are inscribed in the long term – the so-called longue durée in historical terms. The main features of the social and economic organization according to which today’s cities were planned and built are the Fordist production model and the sexual division of labor. As gender studies have shown, these two characteristics are interdependent: attributing the responsibility for caring for the home and for dependents to half of the population – women – without any economic remuneration allows the other half of the population – men – to dedicate their time exclusively and entirely to economic activities in the realm of production.

This organization of productive and reproductive tasks has been reflected in the organization of space since the early 20th century. This is particularly true after the Second World War, when the creation of institutional planning mechanisms in Western countries began permitting a technification, systematization and control of urbanization processes. Thus, the ideas of urban design forged in the first decades of the 20th century became reality in the construction of contemporary cities.

Urban historians have analyzed how ideas about the organization of production and domestic work – transformed into institutional discourses and objectives, and later into instrumental urban planning techniques – configure the spaces that are given over to industry and to domestic life. One outstanding example is the technique of zoning, the cornerstone of urban planning practice during the 20th century, which separates industrial activities from residential areas. The emergence of zoning techniques in Germany in the late 19th century, its later incorporation into American urbanism in the early decades of the 20th century, its transformation into urban planning doctrine by the CIAM in the 1930s, and its clever promotion by Le Corbusier in the 1940s which made the separation of functions into a doctrine of modern urbanism, is a clear example of how ideas about how society should be organized are transformed into technical tools that in turn shape urban spaces.

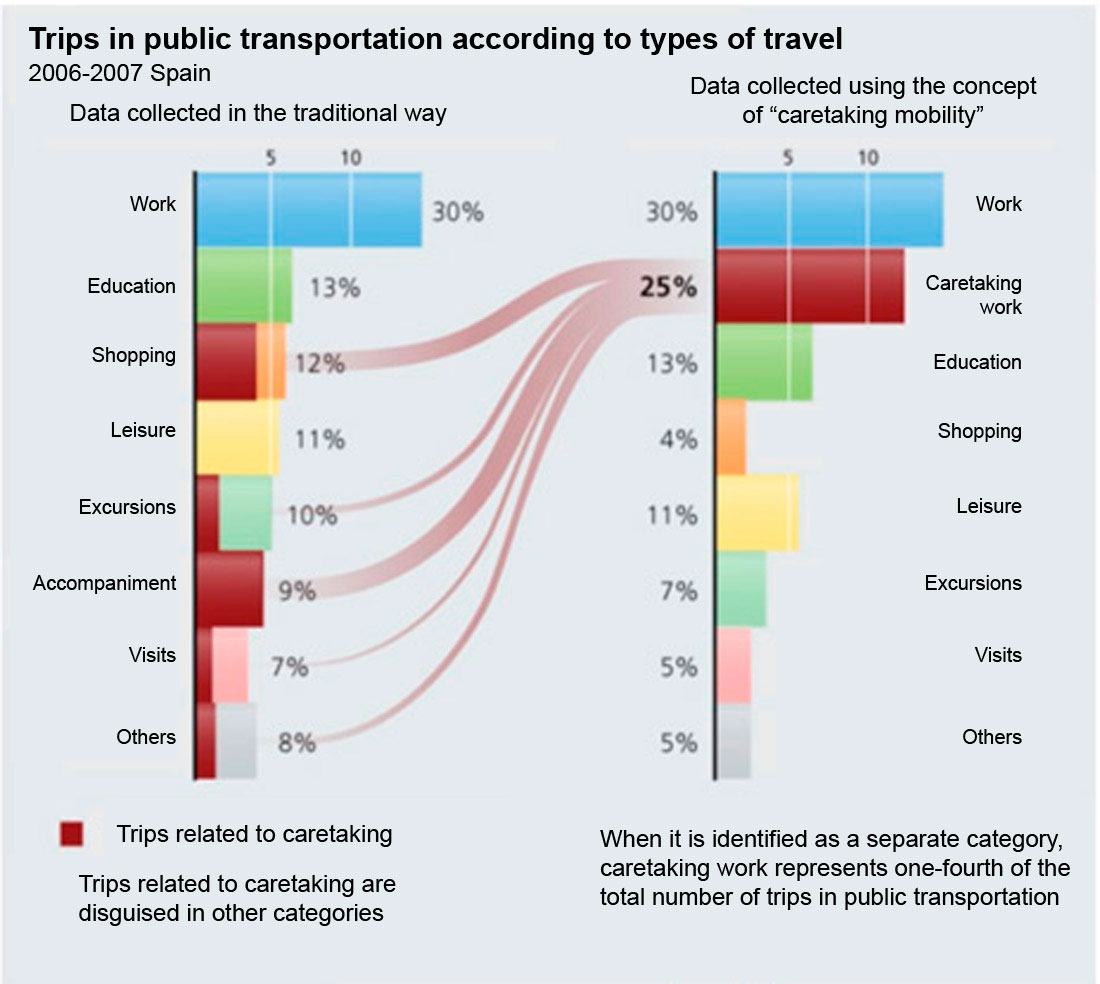

A new umbrella term: “caretaking mobility”. Source: Sánchez de Madariaga, Image by Erik Steiner

Modern urbanism has viewed activities in the productive sphere and in the reproductive sphere as two independent domains that must remain separate spatially. The justification for this separation responds to an economic development strategy that aims to optimize the spatial conditions for industrial and tertiary activities (accessibility, infrastructure, topographic characteristics, etc.). At the same time, it seeks to limit the environmental impact of those activities on residential spaces, in an attempt (expressed explicitly in official discourse) to create a separate sphere, suited to domestic life, for women and children.

For decades that separation did not cause problems for most of the population, since the sexual division of labor remained in force. Men worked in the secondary or tertiary sectors to earn a salary, travelling twice a day between their homes and the workplace, where they spent most of their time. Women, in turn, were responsible for the upkeep of life, taking care of everyday household tasks, within in the limited area of the immediate surroundings of their homes.

As long as people’s life experiences were fragmented and individuals spent their time in only one of these two facets of life – sacrificing family life, in the case of men, and professional life, in the case of women – this organization of the urban space was tolerable. Problems began to arise when people hungered for a fuller life that could give everyone – men and women alike – the chance for personal development: in terms of their capabilities, within the public sphere of professional activity, and in the realm of emotions and relationships in the domain of private life and family life.

While today’s cities were created following (and also fomenting) the model based on a sexual division of labor that has entered into crisis, it is clear today that this organization stands as an obstacle to new forms of life. The measures and policies aimed at favoring the reconciliation of family life and professional life should therefore also apply to urban space and how it is planned. This implies thinking about urban space from the point of view of the needs that are derived from current forms of daily life. This is especially crucial precisely because of the long gestation periods involved in urban transformations and because of the permanence of the results once they have been implemented.

Building a city that can be responsive to the needs of new ways of life requires changes in all areas of urbanism. It implies changes in planning content: i.e., in urban planning’s classic sector-based subjects (transportation, facilities, housing, economic activity, commerce). It also implies changes in planning processes: i.e., in techniques and tools (land-use classification, qualification, management techniques, and inter-institutional coordination, etc.). This is the case because people’s life experiences are multiple and comprehensive. Today’s urban spaces, however, were shaped by an urban planning doctrine that advocated for the separation of functions in urban space (a practice that continues in full force, despite having been questioned for 40 years). The urban milieu thus is fragmented into monofunctional spaces, which are further removed from one another due to the increasing dispersion of urbanization.

The notion of a chain of tasks, linking together the space-time relationships that people establish as they carry out the activities of daily life in the city, is a useful idea in addressing the issue of the spatial dimension of the work-life balance. The chains of tasks performed by individuals on any given day are becoming more and more varied, both from one individual to the next and for the same individual over the course of his or her life, and even from one day to the next. Daily life in contemporary societies is increasingly complicated: multiple activities have to be carried out on any given day, and they take place in different areas of the city.

One example of the chain of tasks carried out on an average day by someone who has young children and also works might be the following: take the child to school; go to work; at lunch time, perhaps pick up the child to have lunch at home; take the child back to school; return to work (if working full time); pick up the child again; maybe shop for groceries; two or three times a week take the child to extracurricular activities (sports, language classes, music lessons); return home; occasionally take the child or an older relative to the doctor. Administrative paperwork also needs to be handled regularly.

In order to carry out all these tasks, the person in question has to travel – using the available means of transport, in the shortest amount of time, with the lowest cost and the greatest possible comfort – to the places where all these activities occur. He or she also has to arrive at those places during the opening hours for the corresponding services.

Things obviously get complicated if there are multiple children and they do not go to the same school (for example, if one is in day care). They get even more complicated when the children are young and there are no day care centers available, no grandparent is available to lend a hand, and there is no money to hire an immigrant worker. There can be further complications if a grandparent loses autonomy and his or her everyday needs also have to be handled: first, they may be instrumental needs, like housekeeping or taxes, but eventually it may also mean managing that household or organizing external aid. If the senior completely loses autonomy and there are no home help services, or residential care facilities, and there are not enough financial resources, someone in the family (usually a woman) will have to leave her job to care for that person.

The type of travel undertaken by people who combine work and family life is polygonal in nature: in other words, there are multiple trips that occur one after the other, normally using different means of transport, which take up a large amount of time. They are different from the pendulum-type travel that is common among people who only work and do not handle family responsibilities.

The fact that, still today, most of these tasks are carried out by women explains the great gender differences in the use of transport. Men travel farther, mainly by car, and they make fewer trips and fewer chained trips. They hardly make any trips for the purpose of accompanying others, and work is the main reason for their travel. Women travel mainly on foot and by public transportation, often traveling with dependents and carrying shopping bags. They chain together more trips, make more trips, make shorter trips and in a more limited geographical area, in closer proximity to their homes.

The fact that women are still responsible for most of the work associated with the reproduction of human life also explains the difficulties that women find in working far away from their homes, with the associated limitations in terms of access to certain sectors of activity and job promotion. This also helps to explain the frequency with which women are forced to work part time or to leave their jobs altogether. All this compounds their economic weakness, reducing their capacity for economic access to urban facilities and services (for example, private transportation or high-cost services, and also housing). In turn, in a vicious circle, that aggravates the restrictions that the current organization of cities imposes on the lives of people who have family responsibilities.

These examples illustrate the many restrictions that urban spaces impose on people who combine work and family life. Summing up, those restrictions are associated with:

· the distances between the places where the different activities are carried out;

· the possibility of covering those distances in short times and affordably;

· the existence of facilities, also reasonably priced and nearby, to provide support in some of the tasks related to reproductive work – mainly facilities for the care of dependents, but also others such as local grocery stores or children’s playgrounds;

· the compatibility of the opening hours of public services, shops, and facilities with working hours, in proportion to distances and the existing means of transportation.

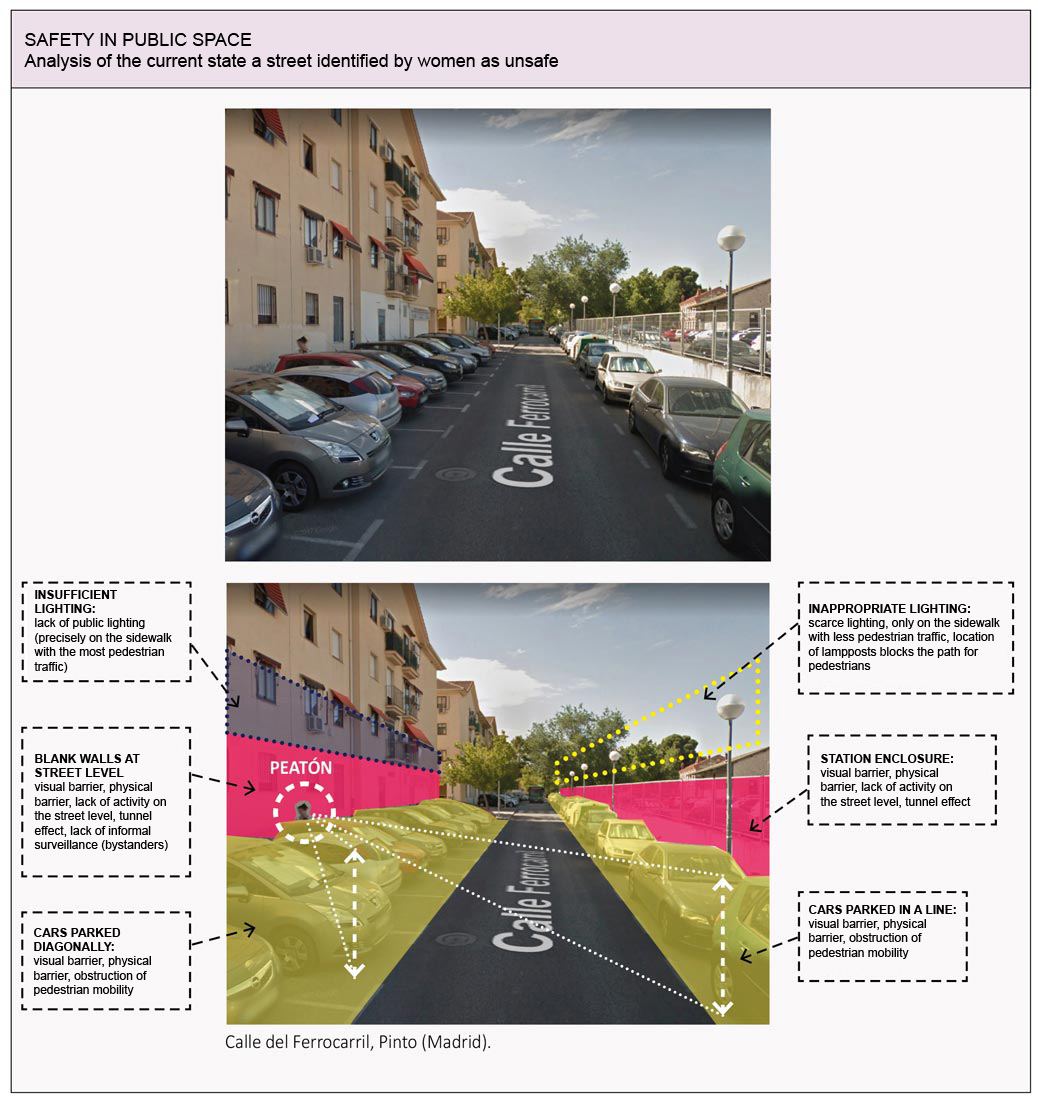

Source: Exploratory Safety Walk in public space with women from the municipality of Pinto. Report of results and basic recommendations. Inés Novella Abril (coord.)

A city that would cater to the populations’ current everyday needs would therefore be a city of short distances, with a mix of uses, with multiple facilities that are accessible on foot or by public transportation and affordable, with a good transportation system to provide access to work opportunities and larger-scale facilities. In other words, it would be a compact and multifunctional city, with public spaces, public transportation and with affordable, high-quality public services and facilities. This city model requires relatively strict urban planning and a relatively high level of public investment.

It is evident that this is not the city model that is derived from current urban planning practices, and implementing it would require substantial changes to the current methods. These changes would impact all scales of planning: from the regional level, to the city level and the neighborhood level, as well the immediate surroundings of each dwelling. Some of the necessary changes would easy to implement, such as widening sidewalks to make it more comfortable and safer to walk with a stroller and while carrying shopping bags. That is currently impossible in many streets in Madrid, including some that have been recently renovated, where making space for parking was given precedence over widening the sidewalks for the benefit of pedestrians (Malasaña).

Other changes would require a substantial shift in current practices. For example, responding to the need for facilities to care for dependents would require significant public investment. The high cost of these services, to ensure they are reliable and of good quality, makes it inviable for them to be provided by the private sector, except perhaps for a very small segment of the population. The very the concept of ‘facilities’ would also need to be expanded, making daycare, nursing homes, and adult day centers the equivalents in planning terms of traditional facilities like healthcare or educational institutions, both with regard to the legislation of regulations and when it comes to drafting city plans.

Prioritizing public transportation over private transportation would imply redirecting the administration’s current investment priorities to favor the former to the detriment of the latter. It would also involve establishing dissuasive measures for the use of private vehicles, and, certainly in the medium term, redirecting and restructuring large sectors of the economy that depend on a continued increase in individual motor vehicle travel.

Encouraging the containment of growth to favor compact models implies controlling the total amount of land that is classified as buildable by the municipalities. This is based on a perspective that takes into account estimated needs within a 15- or 20-year period and distributes the necessary quantities of land in keeping with criteria of accessibility in public transportation within the regional territory. In other words, it would require an effective and real integration between regional planning and transportation planning.

Promoting mixed uses implies changing how land-use qualification techniques are applied (zoning), introducing flexibility and reference standards instead of rigid determinations, and forcing certain minimums in the integration of uses. It would also involve modifying certain methods of managing city making, which favor the creation of homogeneous and monofunctional spaces instead of multifunctional and complex spaces. Here I am referring to the spatial consequences of the actions of an administration that is organized by sectors, without a minimum of mechanisms to coordinate its actions. I am also referring to the actions of public or private urbanizing agents, specialized in real estate products (whether they are shopping centers, business parks or housing) that manufacture such spaces instantaneously. The alternative would be forms of management that aim to construct a city with all its diversity (as was achieved, for example, through the layout and ordinance mechanisms of many 19th-century enlargements).

Access to large-scale facilities (healthcare, education, culture, leisure and sports) which, due to their characteristics, are usually not available to most of the population at the neighborhood level, must be guaranteed by public transportation. This requires associating the locations of large-scale facilities to the public transportation network, as opposed to locating them based on the particular possibilities of obtaining land.

Changes in family structures and in people’s life cycles demand more flexible housing typologies and with a different interior distribution of spaces from what the real estate industry is currently building. Instead of a large bedroom for parents and two or three small bedrooms for children, new family structures demand individual spaces for each of the members the family unit and of a more homogeneous size. Shared responsibility for domestic tasks calls for larger kitchens. The problem of economic accessibility to housing, which affects young people especially, but which affects the growing segment of single-parent households to an even greater degree, calls for a complete reformulation of housing policies.

Spanish society, like European society in general, is undergoing major structural changes that are outlining a very different future model for our society from the one our cities were designed and built for. Aging and the need to reconcile work and family life – which will affect the majority of Spanish citizens, both men and women, in the near future – result in new needs in the city.

The necessary measures encompass all scales and all areas of urban planning. Some can be put into practice easily; others will require structural transformations in urban planning practices on the part of all the agents involved (administrations, developers, residents, associations, construction companies, financial institutions), and which will be more difficult to implement.