Examining the notion of extremes takes us away from a centre point, characterized by its predictability, balance and familiarity, and, instead, moves us towards a condition where unpredictability, disequilibrium and strangeness become the new normal. The way in which we define the familiar centre and its complimentary, capricious extreme and their respective potentials for design intervention and innovation is the primary investigation presented in ds.

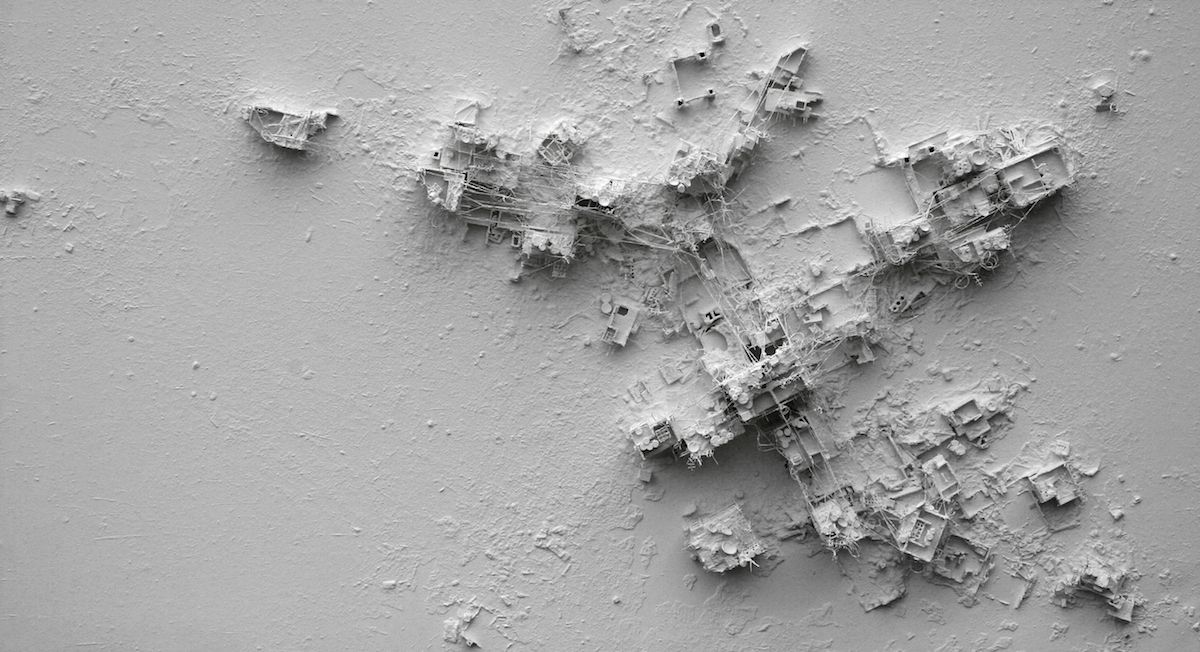

Angels, 2006. Mixed media and acrylic gesso on canvas © Gerry Judah

The condition of extremes suggests a tipping point; a moment in which a system shifts from one state to another, often unpredictable state. In many cases, the condition of extreme arises from a singular force exerting its impact on a region, to the detriment of other modes of inhabitation. As such, the conditions of extremes demands new tropes: new models of practice, new typologies of buildings, infrastructure and landscapes, and new pairings of program or infrastructure. The question remains: what is the role of architecture or infrastructure in such contexts? to redress? to mitigate? to capitalize on new opportunities?

Key to the understanding the implications of extremes is the relationship that it has to risk: the further we move away from a state of equilibrium, the more volatile the situation becomes, the more exposure we have to danger and loss, the more risk we take on. Do the risk/reward models familiar on the trading floors of global financial markets and real estate speculation projects hold up in design disciplines? How can risk and extreme circumstances be leveraged as a new, productive model for architecture; a model emphasizing speculation as a way to test scenarios, outcomes and tools?

Ulrick Beck, in Risk Society, argues that: “being at risk is the way of being and ruling in the world of modernity…global risk is the human condition at the beginning of the twenty-first century.” Until now, the developed world has largely been able to successfully displace the economic, environmental and political impact of its development to other nations and peoples, or other groups and stakeholders within their own nations, rendering the risk invisible. However with the financial crisis of 2008, and the increasingly tangible impacts of climate change, complete displacement of risk is no longer possible. The distant other is becoming inclusive not through mobility, but through shared risks, Beck argues. For one group or region to achieve seeming stability, another will likely lose it, given the voracious nature of the capitalist system, and its environmental costs. Beck thus asks: “is there an enlightenment function and a cosmopolitan moment of world risk society? What are the opportunities of climate change and the financial crisis and what form do they take?”

Why the contemporary fascination with extremes? On the one hand, we are flooded, through the media, to daily series of economic, environmental and social disasters. These situations test our sense of order, and in relation to design, challenge the question of what is the fine line between fiction and possible futures? These scenarios challenge the viewer to revisit our contemporary biases and expectations Extreme environments and conditions become a test of Design’s ability and ingenuity, begging the question: are there limits to the degree that we can reasonably engineer our environments in the future? And as our physical environments continue to change at ever faster rates, will notions of ‘before’ and ‘after’ states cease to be meaningful, but instead suggest that our environment is in a continuous, unfolding and ungraspable state of perpetual transformation.

Ulrick Beck suggests that our contemporary conditions of risk might initiate alternative models of governance by encouraging new networks of actors, and might give those typically marginalized a greater voice, by rendering material the impacts of our risk society. The collection of investigations in Bracket [at Extremes] similarly argues that a set of alternative spatial logics, actors, agents and networks are possible in our contemporary environments. By venturing away from a comfort of the known, new roles, territories and agencies for architecture and design are suggested. Not a lament for what has changed or been lost, the projects and essays collected here look lucidly but optimistically to these new conditions of risk and imbalance, and seem to see opportunities for invention.