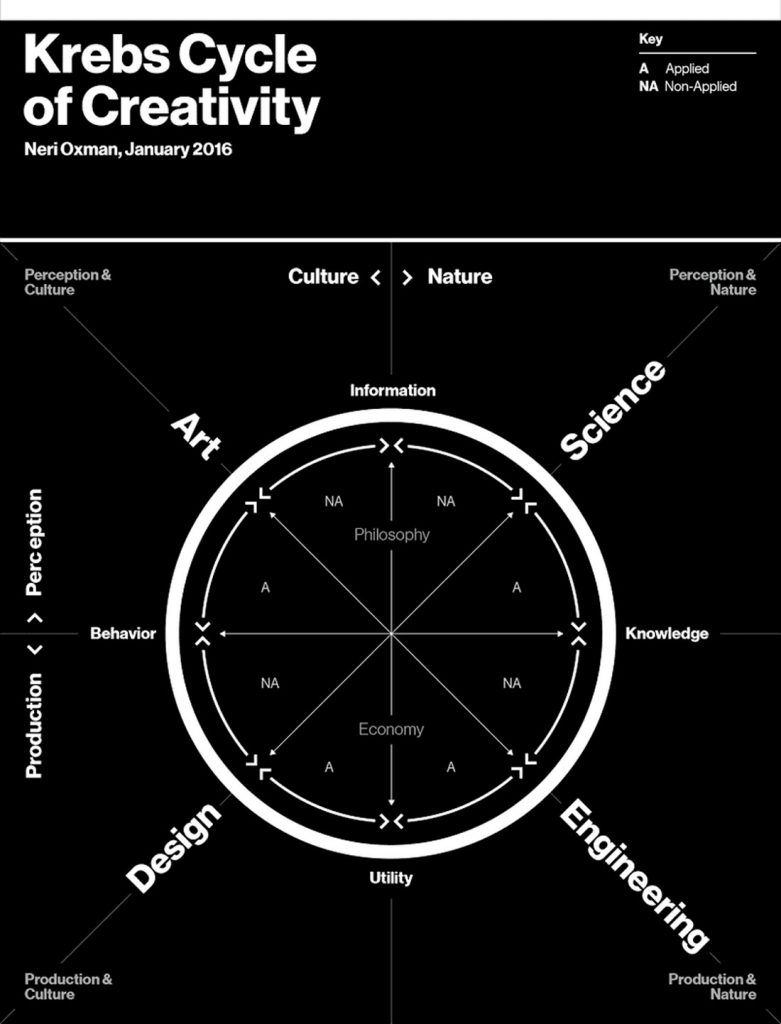

On Professor Neri Oxman’s Krebs Cycle of Creativity of the relationship between the disciplines, design and science are opposite one another on the circle, and the output of one is not the input of the other as is often the case of engineering and design or science and engineering. I believe that by making a “lens” and a fusion of design and science, we can fundamentally advance both. This connection includes both the science of design and the design of science, as well as the dynamic relationship between these two activities.

As I have written previously, one of the first words that I learned when I joined the Media Lab in 2011 was “antidisciplinary.” It was listed as a requirement in an ad seeking applicants for a new faculty position. Interdisciplinary work is when people from different disciplines work together. But antidisciplinary is something very different; it’s about working in spaces that simply do not fit into any existing academic discipline–a specific field of study with its own particular words, frameworks, and methods.

For me, antidisciplinary research is akin to mathematician Stanislaw Ulam’s famous observation that the study of nonlinear physics is like the study of “non-elephant animals.” Antidisciplinary is all about the non-elephant animals.

I believe that by bringing together design and science we can produce a rigorous but flexible approach that will allow us to explore, understand and contribute to science in an antidisciplinary way.

In many ways, the cybernetics movement was a model for what we are trying to do–allowing a convergence of new technologies to create a new movement that cuts across the disciplines. But it is also a warning: cybernetics became fragmented through over formalization and “disciplinarification.” As Stewart Brand recently reflected, cybernetics became more and more dense and academic, and as it matured it was “bored to death.” Perhaps we can design something that is both rigorous enough, engaging enough, and antidisciplinary enough not only to survive, but to thrive.

The kind of scholars we are looking for at the Media Lab are people who don’t fit in any existing discipline either because they are between–or simply beyond–traditional disciplines. I often say that if you can do what you want to do in any other lab or department, you should go do it there. Only come to the Media Lab if there is nowhere else for you to go. We are the new Salon des Refusés.

When I think about the “space” we’ve created, I like to think about a huge piece of paper that represents “all science.” The disciplines are little black dots on this paper. The massive amounts of white space between the dots represent antidisciplinary space. Many people would like to play in this white space, but there is very little funding for this, and it’s even harder to get a tenured positions without some sort of disciplinary anchor in one of the black dots.

Additionally, it appears increasingly difficult to tackle many of the interesting problems–as well as the “wicked problems”–through a traditional disciplinary approach. Unraveling the complexities of the human body is the perfect example. Our best chance for rapid breakthroughs should come through a collaborative “One Science.” But instead, we seem unable to move beyond “many sciences”–a complex mosaic of so many different disciplines that often we don’t recognize when we are looking at the same problem because our language is so different and our microscopes are set so differently.

With funding and people focused on the disciplines, it takes more and more effort and resources to make a unique contribution. While the space between and beyond the disciplines can be academically risky, it often has less competition; requires fewer resources to try promising, unorthodox approaches; and provides the potential to have tremendous impact by unlocking connections between existing disciplines that are not well connected. The Internet and the diminishing costs of computing, prototyping and manufacturing have diminished many of the costs of doing research as well.

A Prehistory of the Anti-Disciplinary: Cybernetics

Although the new technologies and tools diminishing costs driven by the Internet and Moore’s Law makes antidisciplinary work increasingly possible, it’s not exactly a new idea.

Driven less by the diminishing costs, but rather by a whole set of enabling technologies and tools, a similar movement was occurring in the 1940s and 1950s where a variety of fields began to converge. Applications from ballistic missile control to understanding how biological systems regulated movement brought engineers, designers, scientists, mathematicians, sociologists, philosophers, linguists, psychologists and thinkers from a variety of fields together to begin to understand systems and feedback loops as a way to both comprehend and design complex systems. This type of cross-disciplinary study of systems was termed “cybernetics.”

Although mathematician and philosopher Norbert Wiener and his book, Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine is often what first comes to mind when when we think of cybernetics, much of “first-order cybernetics” was heavily in the domain of the engineers. (First-order cybernetics was about how one used feedback systems and feedback loops to control or regulate systems, and second-order cybernetics was more about self-adaptive complex systems and systems that could not to be controlled or were highly complex.)

Although they get less attention, there were also many philosophers, sociologists and cultural figures involved in cybernetics, such as Heinz von Foerster, Gregory Bateson, Margaret Mead, Gordon Pask, and Stewart Brand who were more concerned with second-order cybernetics.

Some called second-order cybernetics the community of first-order systems. Second-order cybernetics was more about participant observers than objective observers/designers. For example, a first-order cybernetic system would be a thermostat and a second-order system would be the earth’s ecosystem. An engineer designs a thermostat as an object that they can understand, control and is for a user that they can talk to, but the ecosystem is something we live in as a participant, can’t control, and adapts to our actions. And beyond complexity and the impossibility of regulating such complex systems, by bringing the human into the system second-order cybernetics goes beyond the move from “objectivity” to “subjectivity” and makes the participants responsible for what they pay attention to and what they value. And if “cybernetics is the theory, design is the action.” (Ranulph Glanville)—for we are responsible for what we design.

While many of the origins and threads of cybernetics ran through MIT, by the time the Media Lab was established in 1985, the vibrant cybernetics movement had disappeared into a variety of applied disciplines. But it has left its mark: design, and in particular, “design thinking,” emerged and survives today as a practice that cuts across many of the disciplines that were touched by it.

Evolving Design

Design has become what many of us call a “suitcase word.” It means so many different things that it almost doesn’t mean anything: you can call almost anything “design.” On the other hand, design encompasses many important ideas and practices, and thinking about the future of science in the context of design–as well as design in the context of science–is an interesting and fruitful endeavor.

Design has also evolved from the design of objects both physical and immaterial, to the design of systems, to the design of complex adaptive-systems. This evolution is shifting the role of designers; they are no longer the central planner, but rather participants within the systems they exist in. This is a fundamental shift–one that requires a new set of values.

Today, many designers work for companies or governments developing products and systems focused primarily on making sure that society works efficiently. However, the scope of these efforts are not designed to include–nor are they designed to care about–systems beyond our corporate or governmental needs. We’re moving into an era where the system boundaries are not as defined. These underrepresented systems, such as the microbial system and the environment, have suffered and still present significant challenges for designers. While these systems are self-adaptive, complex systems, our unintended effects on them will most likely cause unintended negative consequences for us.

MIT Professors Neri Oxman and Meejin Yoon teach a popular class called “Design Across Scales,” where they discuss design at scales ranging from the microbial to the astrophysical. While it is impossible for designers and scientists to predict the outcome of complex self-adaptive system, especially at all scales, it is possible for us to perceive, understand, and take responsibility for our intervention within each of these systems. Also, as a “participant” we can engage at each of these scales if we are aware of and able to use all of our lenses by being aware of the systems that we are in and being continuously preceptive. This would be much more of a design whose outcome we cannot fully control–more like giving birth to a child and influencing its development than designing a robot or a car.

An example of this kind of design is the work of MIT Professor Kevin Esvelt who describes himself as an evolutionary sculptor. He is working on ways of editing the genes of populations of organisms such as the rodent that carries Lyme disease and the mosquito that carries malaria to make them resistant to the pathogens. The specific technology – CRISPR gene drives – are a type of gene edit such that when carrier organisms released into the wild, all of their offspring, and their offspring’s offspring, and so on through the generations will inherit the same alteration, allowing us to essentially eliminate malaria, Lyme, and other vector-borne and parasitic diseases. Crucially, the edit is embedded into the population at large, rather than the individual organism. Therefore, his focus is not on the gene editing or the particular organism, but the whole ecosystem – including our health system, the biosphere, our society and its ability to think about these sorts of interventions. To be clear: part of what’s novel here is considering the effects of a design on all of the systems that touch it.

The End of the Artificial

Unlike the past where there was a clearer separation between those things that represented the artificial and those that represented the organic, the cultural and the natural, it appears that nature and the artificial are merging.

When the cybernetics movement began, the focus of science and engineering was on things like guiding a ballistic missile or controlling the temperature in an office. These problems were squarely in the man-made domain and were simple enough to apply the traditional divide-and-conquer method of scientific inquiry.

Science and engineering today, however, is focused on things like synthetic biology or artificial intelligence, where the problems are massively complex. These problems exceed our ability to stay within the domain of the artificial, and make it nearly impossible for us to divide them into existing disciplines. We are finding that we are more and more able to design and deploy directly into the domain of “nature” and in many ways “design” nature. Synthetic biology is obviously completely embedded in nature and is about our ability to “edit nature.” However, even artificial intelligence, which is in the digital versus natural realm, is developing its relationship to the study of the brain beyond merely a metaphorical one. We find that we must increasingly depend on nature to guide us through the complexity and the unknowability (with our current tools) that is our modern scientific world.

By picking up where cybernetics left off and by redirecting the development of modern design to the future of science, we believe that a new kind of design and a new kind of science may emerge, and in fact is already emerging.

Rethinking Academic Practice

MITx and edX are now helping the world by making lectures, knowledge, and skills available online to students everywhere in an organized way. The MIT Press, the Media Lab, and the MIT Libraries could serve a parallel role by creating a new model for academic interaction and collaboration, breaking down the artificial barriers dividing intellectual discourse. Our thinking is to create a vehicle for the exchange of ideas that allows all those working in the antidisciplinary space between and beyond the disciplines to come together in unexpected and exciting ways to challenge existing academic silos. Our aim is to create a new space that encourages everyone, not just academics, to come together to create a new platform for the 21st century: a new place, a new way of thinking, a new way of doing.

Much of academia revolves around publishing research to prestigious, peer-reviewed journals. Peer review usually consists of the influential members of your field reviewing your work and deciding whether it is important and unique. This architecture often leads to a dynamic where researchers focus more on proving the value of their research to a small number of experts in their own field than on taking the high-risk of an unconventional approach. This dynamic reinforces the cliché of academics: learning more and more about less and less. It causes a hyper-specialization where people in different areas have a very difficult time collaborating–or even communicating–with people in different fields.

Peer-reviewed academic papers were a very important system to build scientific knowledge before the Internet, but in many ways, they may be holding us back now. Stewart Brand likens academic papers to tombstones reading: “we thought this subject to death and this is where we buried it.” I propose iteratively designing a new antidisciplinary journal with an open collaborative model of interaction in contrast to the structured and formal peer review system in order to tackle the most pressing and most interesting problems and ideas of our times and itself be an experiment.

The Media Lab has thrived 30 years without losing its relevance or its passion when most research labs that focus on a discipline have difficulty retaining relevance for so long. Why? I think it’s because our focus is on a way of thinking and doing rather than on a field of study or a particular language. I believe the key is a focus on developing a better system of design and a better theory of deployment and impact.

As participant designers, we focus on changing ourselves and the way we do things in order to change the world. With this new perspective, we will be able to tackle extremely important problems that don’t fit neatly into current academic systems: instead of designing other people’s systems, we will redesign our way of thinking and working and impact the world by impacting ourselves.