Catherine Fennell signed up as a participant in one of our rammed earth workshops. It wasn’t until we were back-to-back, tamping inside a 7-by-1.5-foot box, in the hot late August sun, that Cassie explained her connection to the area. As it transpired, she had been following the Soil Lab project for several months from a distance, in connection with her own research concerning urban landscapes formed through residential demolition. From those early conversations on-site grew a deep respect for a friend and mentor who helped us navigate sensitively the challenging context we found ourselves in.

In early 2019 I overheard an unexpected conversation between two middle-aged men—unexpected because it involved a landscape far from the one unrolling right before us. Their badges told me their names, employers and destination that morning: they were soil scientists, both on their way to an annual professional meeting being held that year in San Diego. As the Pacific Ocean took shape beyond the bus windows, they began to trade remarks about land use. One noted that California’s southern coast had never really been an ideal place for large-scale agriculture. Not enough fresh water, he observed, too sandy. Given that, he continued, the tangle of tourist hotels and entertainment venues flashing by made sense. “It’s not like this is Chicago,” his companion chuckled, “all that prairie” “paved over” in “concrete and asphalt.” Beneath the pavement, the prairie.

Just where did this prairie go, the glacial till upon which so much dark, well-drained nutrient-dense silt and sod had settled? The men on the bus offered one answer: rapid industrialization had swallowed up the continent’s most fertile soils as Chicago rose to industrial prominence in the late 19th century and kept right on sprawling across its hinterlands. They are not alone in imagining a vanished prairie; Daniel Burnham, one of Chicago’s most renowned architects and planners, peppers his 1909 masterplan for the city with references to a primordial prairie filled with “only” “waving grasses” and “brilliant wildflowers.” He laments the loss of the prairie, even while he proposes it as the testing ground for an orderly and endless urban growth.

A different kind of answer emerges with the recognition that this landscape was in fact never—save its flowers and grasses—empty. Indigenous groups had long reckoned with this watery landscape. They developed a network of portages and trails, and in the process they transformed a soggy place into a hub of intra-continental trading and transit. Euro-Americans plonked their “city in a garden” on top of that infrastructure. Beneath the pavement, then, was maybe never really the prairie. Beneath the pavement, a swamp.

In the summer of 2021, Soil Lab landed on a vacant lot in a western part of Chicago now known as North Lawndale. The name “Lawndale” was always a misnomer, historian Beryl Satter suggests, dreamed up in the 1870s by developers who had hoped that its lush connotations would attract middle-class residents. “[T]he only grass to be found [even then],” Satter writes, “was in its two city parks.” Development took off in the aftermath of Chicago’s Great Fire in 1871, as industrialists came in search of sound places to rebuild their factories and warehouses. Czech, German and Irish immigrant laborers followed close on their heels. They settled into the brick cottages, row houses and townhomes that came to line the manufacturing facilities, also made of brick. Such “fireproof” constructions could only emerge following efforts to drain the soggy ground. In a city gripped with feverish expansion, those efforts proved uneven. To this day, local property owners reckon regularly with flooded basements, the effect of so much hasty construction upon unstable ground. Beneath the pavement, no longer just a swamp. Beneath the pavement, the fill.

By the 1930s, Lawndale—as it was originally known—had become one of Chicago’s densest and most populous areas. Russian and Polish immigrants began arriving during the early decades of the 20th century, chasing manufacturing work. Yet, more established residents would not rent to them. Scholars like Matthew Jacobson and Karen Brodkin underscore how American race politics at the time positioned Jewish immigrants as adjacent to—yet not quite—“white.” While Jewish newcomers faced discrimination, Satter shows that some did manage to acquire vacant lots upon which they constructed large apartment buildings to meet growing housing demands within their community.

And so Lawndale became increasingly dense as it became increasingly Jewish. It would not remain that way: as housing opportunities increased in the 1950s for Jewish people elsewhere, wealthier residents left to pursue them. Speculators, brokers and investors sensed an opportunity. They bundled together properties and offered them to yet another group that had begun arriving in the 1930s and 1940s: Black migrants from the American South. Newcomers relied on contract sales to acquire property because intense and violent forms of racial discrimination shut them out of favorable mortgage arrangements available to other Americans. They faced exorbitant down payments and interest rates for substandard housing. High demand meant that unscrupulous brokers could forgo regular maintenance. When a buyer got behind on their payments, brokers simply evicted them, retained past payments and cycled the deteriorating property into another unfair yet utterly legal contract sale. Above the pavement, another swamp: this one mired in American racism, its trenchant inequities and scandalous profits.

Chicagoans often narrate the vacancy that besets West Side neighborhoods like North Lawndale through a singular event: the civil disturbance that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr in 1968. King had lived in Lawndale while community organizing in the urban Northern states. To hear many tell it, his assassination unleashed a destructive rage characterized by arson, looting and property destruction. When bulldozers finally cleared away the rubble, this story goes, they left behind gluts of vacant lots that still plague these neighborhoods today. As powerful as this narrative may be, it papers over what historical maps and the recollections of long-term residents make clear. Buildings in these areas had begun to disappear already in the 1940s. Over the next six to seven decades these buildings fell in fits and starts. Some fell to urban clearance and renewal projects aimed at combatting “blight,” others to smaller-scale demolitions aimed at containing devaluation, residential flight and deindustrialization, and others to ensuing neglect and inadequate maintenance. Such protracted demolition has opened ample space for new and long-term residents. More than a few will wax agrarian when speaking of the lots they have come somehow to occupy, acquire, build, cultivate or speculate upon. “The little fields,” some will say when referring to these places; “the prairie” say others. Amid another swamp, and the violent clearings it pressed upon buildings and their inhabitants, yet another prairie.

Those closest to the ground know that if they stand now in a “prairie,” it is an especially peculiar one. Car parts, garbage sacks and matted clothes clot its grasses and wildflowers. When it rains, a young gardener explained to me in 2019, and when it thaws, “the earth just births glass.” She is far from the only gardener to have noticed the glass, brick, slag, tiles, pipes, wood and wiring but also the clinkers, paint chips, carpets, bottles and dishes that well up with the weather. A long-practiced—albeit no longer permitted—disposal strategy in the region had wreckers repurposing demolished buildings to fill the “holes” that demolition opened within the landscape. They folded building debris into remaining foundations, tamped the pile down and drove away. The concaves and mounds that now dot vacant lots on Chicago’s West Side have emerged as building debris has subsided. Those who work this strange ground know that for every discernable object it yields, there is much more that they cannot see. The young gardener I spoke to worries about the toxins that her cats and dogs might be ingesting but also spreading as they tramp around vacant lots, lick their paws and snuggle with her inside. Beneath this strange prairie, more fill, and so much of it unknown.

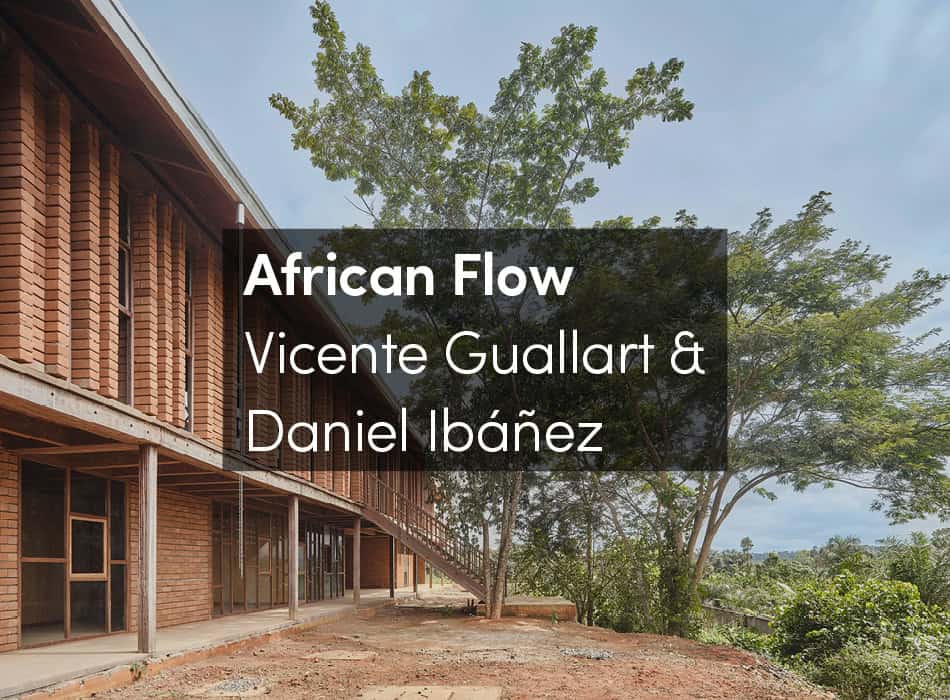

The open call to participate in the Chicago Architecture Biennial, to which Soil Lab’s designers responded, defined a vacant lot as “an area of land within an urban setting that is not built upon.” It stressed that like many of the 10,000 vacant lots owned by the City of Chicago, the lot Soil Lab eventually occupied was “rough” and “raw” with “limitless potential.” It welcomed proposals that would route such potential through the theme of The Available City. Soil Lab’s proposal did just that by focusing on local vernacular architecture and vernacular materials. The proposal drew inspiration from North Lawndale’s ubiquitous brick architecture. It also imagined mobilizing ancient construction techniques that directed would-be builders, as one of the designers put it, “to the earth in front of you and the shovel in your hand.” Above the earth, but also through it, the bricks.

Limits to potential nevertheless ensued. Some limits were logistical: materials held up in customs, team members held up by travel restrictions. Others emerged from the site itself, from the fact that most vacant lots that do not appear built upon have in fact been built upon in the past. The ground is not exactly “earth” but rather the residue of demolitions driven by devaluation, discrimination and displacement. Those residues are anything but transparent; they are perhaps even something unhealthy. Lab tests, for instance, showed on-site soils to have substantial levels of lead, a potent neurotoxin common in American paints and gasolines until the late 1970s. Having no budget or time for remediation, the biennial’s coordinators advised Soil Lab that no ground should be broken. The rammed earth blocks would be built on-site from material brought in. Those blocks would rest atop a wall of standard bricks, and that wall would have to rest on the concrete pad that remained on-site, a remnant of past building.

The designers felt the disappointment of thwarted plans. And yet this strategy to contain rather than free up available materials conforms to common regulations in the United States. For generations, Americans have been told that lead and other toxins pose relatively few health risks when held behind a clean and even layer of paint, wallpaper or tile, or covered up by a firm barrier. Soil Lab’s lot had the benefit of an existing concrete slab. Other lots in the biennial used wood chips to create a barrier. Behind the walls of obsolete residential buildings, beneath the pavement and mulch that cover the vacant lots they become, the byproducts of late industrial capitalism.

Soil Lab raised its pavilion on the extant concrete pad. Over the fall of 2021, it hosted several workshops about bricks, brick making and ceramics. Despite efforts to retain the space for community use, rumors had it that the lot would eventually go to affordable housing construction. Little remains of the structure today. Indeed, the City of Chicago announced the sale of some 4,000 vacant lots on the South and West Sides in October 2022. On the West Side, these sales will bolster conventional housing developments designed to maximize property tax revenue. As much as the biennial’s vacant lots might have embodied “limitless potential,” and as much as the biennial might have sketched out numerous visions for realizing such potential, vacant lots are becoming “available” only to the most mundane development imaginations. Across the vacant lot, and its latter-day prairies and clearings, the predictable horizons of urban growth would seem to be unrolling yet again.

In the face of impending vacant land sales in places like North Lawndale, it would be possible to fold a project like the biennial into broader revaluations fueled by so many booms and busts and so many demolitions and displacements. Yet such a conclusion would ignore the challenge posed by Soil Lab’s thwarted designs, and more pointedly by residents who have been breaking local ground in their efforts to raise plants and animals and recreation and gathering spaces, amid utter uncertainty about what these grounds hold. Rather than repave the material footprints of racism and industrial life by looking past them, these efforts insist on engaging with their risks, uncertainties, even their pleasures. They challenge urbanites to consider what it would mean to build self-consciously in—but also with—a world in which the dump is not so much elsewhere as it is everywhere, albeit it in radically uneven distributions. Beneath the pavement, then, lies the outlines of the most sobering and clear-eyed beach.