This essay discusses a new neighborhood currently being designed for kibbutz Hatzor in the south of Israel. The guiding principles of this project respond to the social and economic changes undergone by the kibbutz in recent years—primarily the shift away from a collective lifestyle towards a more private one, centered around the family household. The project proposes a neighborhood model that combines individual and shared ownership: private single-family homes set within the agrarian landscape supported by the cooperative structure of the kibbutz. The project searches for a middle ground between two distinct ways of living—the socialist idealism of early kibbutz settlements, and the privatized lifestyle of the detached suburban house, dominating residential developments outside Israeli metropolitan centers.

The kibbutz, a cooperative settlement type based on social equality, sharing and mutual aid, emerged in the early twentieth century as part of the Zionist effort to create a new utopian society engaged in production and rooted in the land. With the intention of building a self-sufficient community based on domestic partnership, kibbutz members collectively owned property, managed work division and voted on all decisions regarding the livelihood of the community and the individuals that constituted it.

The kibbutz enacted both the political and socialist ideals of the Zionist movement and the Israeli state. It served as a means to spread the Jewish population in Palestine by creating rural outposts, and as a melting pot for the transformation of the immigrant urban European Jew into an Israeli farmer-pioneer. Despite the relatively small percentage of the population living in the kibbutz settlement type, the kibbutz movement became a dominant political and economic power in the then social-democratic Israeli State—intellectual and military leaders, as well as contributing up to forty percent of the country’s agricultural product.

The urban and architectural design of the kibbutz introduced a new kind of settlement plan. The settlement was conceived as a single plot of collectively owned land (provided first by the Zionist movement and later by the Israeli state) with dispersed buildings within it—a spatial layout that reflected a new organization of daily life: children raised collectively in a children’s house and meals eaten communally in the dinning hall. .Without the need for distinct kitchens, living rooms and utility areas, the dwelling unit was reduced to a sleeping room for an individual or couple. Scattered across an abundant, often meticulously landscaped, open green space, the dwelling units were organized around a network of pedestrian-bike paths, which connected them to each other and to the core collective spaces of the community. Architecture and landscape merged to create a continuum of open and enclosed spaces. From an urban-rural point of view the kibbutz introduced a unique living environment that was almost entirely car free, rich in landscape and greenery, modest in housing and human in scale. [i]

With the socio-economic and political changes of the past decades, including the spread of capitalism within and outside Israel, the Kibbutz as a socialist ideal began to destabilize and forced to undergo radical transformation. The return to a family structure in which children and parents live together rendered the single room dwelling unit of the kibbutz obsolete—additions were made to the unit to make room for all the programs that now belonged to the single family. Several kibbutz communities even established new neighborhoods to accommodate these new family homes. However, very often, the urban layout of these neighborhoods followed the suburban model of subdivision, which in Israel and many other places across the world, was the most readily available settlement typology for detached single-family houses. The insertion of this privatized and individualized typology into the delicately balanced collective space and life of the kibbutz devastated and damaged the kibbutz’s physical and social landscape.

In recent years there has been a renewed interest in the kibbutz from a growing population of young families seeking an alternative to the high cost of urban and suburban living. Not to mention, the urban layout of pedestrian paths, small homes and collective programs has provided younger generations with the opportunity to participate in an environmentally responsible and sustainable community outside the city.

Kibbutz Hatzor, a medium size kibbutz of approximately 600 members, located 10km east of the port city of Ashdod, began to sense a growing demand for adequate family housing among existing members and newcomers wishing to join the community. Acknowledging the danger in adapting the conventional suburban subdivision, the kibbutz planning committee asked me to prepare a vision plan for its future growth—one that would accommodate new neighborhoods yet preserve the kibbutz’s unique landscape, relation to open space and notion of collectivity. The project proposed a set of urban strategies and plans for retrofitting several parts of the kibbutz, as well as the design of a new neighborhood presented here.

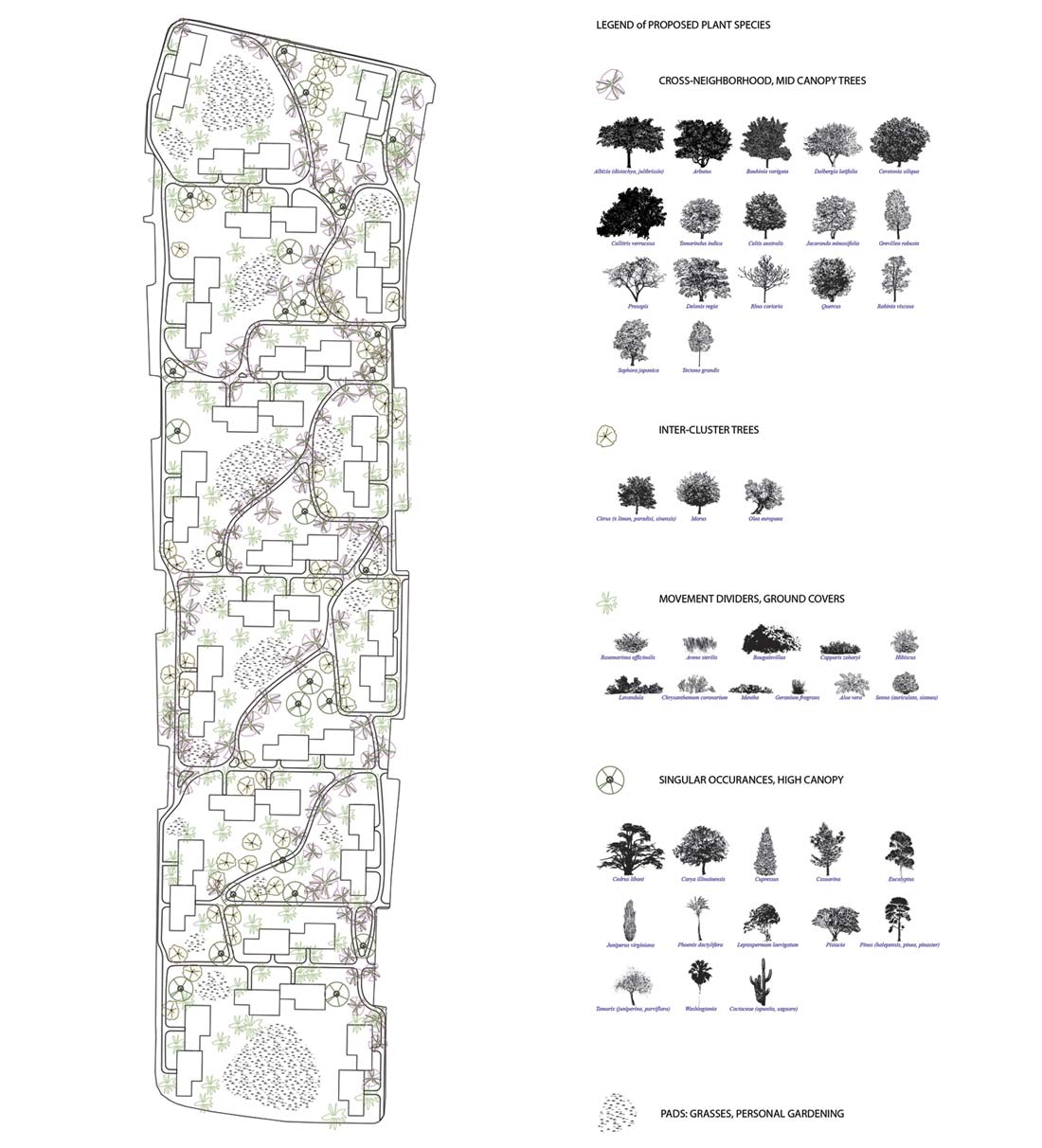

Situated on a rectangular site along the western boundary of the kibbutz, the new neighborhood consists of 44 houses arranged in a series of six clusters—each cluster surrounds a collective square yard, and is made up of six to eight homes organized into two “L” shaped forms. Shared facilities—storage, bike parking, vegetable gardens, play areas and communal rooms—are located at the corners of the “L” buildings and within the yard. While the car is relegated to a perimeter road (within close proximity to all houses), pedestrian and bike paths cut through the clusters, connecting the houses and open spaces to the existing network of paths.

The ownership structure follows a similar economic model that many kibbutz settlements have adopted in the

The dominant architectural element of this new neighborhood is the roof. Anchored through the wet zones of the house and supported by perimeters columns, the roof acts as a “collective urban element:” an overarching frame for the cluster as a whole and for the individual family homes. The maximum buildable area allowed for each lot in this case is defined by the extent of the roof, while the actual size of interior spaces and number of rooms, is determined by each tenant and can easily change through time. In this way, the project is both fixed and open-ended, combining a pre-designed architecture with a self-built approach, allowing for equality and collectivity while enabling self-expression and individual choice.

In addition to its unifying purpose, the roof attains an active and passive energy role. Its primary south orientation accommodates the harvesting of solar energy through an integrated photovoltaic tile system. The roof overhangs the footprint of the interior spaces to create shaded outdoor areas, minimizing direct sunlight on exterior walls and reducing the heat intake of the house.

As a tool to service the community and the individual family, the architecture stabilizes a social structure and defines a relationship between private and collective life. While the new neighborhood includes individual lot lines that demarcate the area owned by each household, these lines do not abide to the conventional public-private binary that divides “mine” from “theirs.” Rather the design configures a spatial organization as a gradient of private to shared space (of “mine” to “ours”): owned to some degree by all the members of the kibbutz. Therefore this project talks about degrees of collectiveness, varying spaces of engagement and participation. Through a sequence of movements, spaces and simple building forms a physical framework is created that balances shared and individual space.