The theme proposed by the main curator of the Venice Architecture Biennale often reacts ideologically to that of the previous one. For many years the selected title defined a relatively lax framework that permitted the incorporation of a large number of prestigious architects who, in addition to magnificent architecture, brought glamour to the Giardini during the days of the inauguration. Surprisingly, in the last Biennale, Rem Koolhaas proposed focusing all of the attention of the exhibition on architecture itself. The “Elements of Architecture” exhibition was organized around an investigation analyzing the design of fundamental elements used to construct architecture in different historical periods and contexts. The result was tremendously effective in resolving the contradiction between his position as curator of an exhibition positioned against architecture as spectacle, and his own condition as an architectural celebrity. The exhibition contents were generated through the analysis of building fragments, the majority of them anonymous, which left the so-called “starchitects” out of the conversation.

This year Alejandro Aravena introduced a different perspective with the title “Reporting From the Front,” claiming the practice of architecture as an instrument for improving the living conditions of the least privileged members of our society. If in the 2014 exhibition Koolhaas invited all national pavilions to reflect on how each country had absorbed modernism, this year Aravena proposed sharing the main challenges that architecture has had to deal with in recent years. A visit to the Biennale’s national pavilions would serve not only to contemplate the latest avant-garde projects, but also to learn about, and perhaps anticipate, possible conflicts in different geographical contexts that the profession may have to face in the near future.

Spain is probably one of the countries where the impact of the economic crisis of 2008 has affected most deeply the practice of architecture. There are not many places on the planet where such an incredible amount of structures were built in a short period of time, in many cases with no other intention than feeding the voracious appetite of the motor that was driving the economy. The lack of reflection with respect to the necessity of these projects resulted in many cases in abandonment due to the economic unviability of their completion or maintenance. Their appearance in the Spanish landscape has generated a collection of unfinished buildings, which exemplify the madness of recent years, when the consideration of change, adaptability and evolution over time was removed from the formula for making architecture. Nobody knows how long these structures will remain in this unfinished state. Some of these contemporary ruins will be adapted to new uses, yet others will remain for many years frozen as useless objects in the landscape.

The hope that if we could report and share this sad situation so other emerging economies wouldn’t fall into the same mistakes, was the starting point of the exhibition. ¨Unfinished¨ was materialized in the central space of the Spanish Pavilion with a hanging movable structure where the work of seven photographers was condensed in fifty-five images with a critical vision of the disasters of the real estate bubble.

Some of the most critical narratives were articulated by the photographs by the collective Cadelasverdes, whose series “Spanish Dream” included everyday domestic scenes in surprisingly unfinished architectural backdrops. These snapshots were taken in half-finished structures with raw interior spaces, where the quotidian nature of the scenes strike us as the inhabitants behave obliviously to the fact that they are living in a ruin. Not much economic effort would be needed to make these ruins inhabitable again.

Photographer Adrià Goula in his work “Re-edificatoria” documents half-built, half-demolished structures in a stage when it is still possible to read the traces that reveal the construction process. The spaces lack any type of refinement or embellishment and are dominated by the raw materials that were never hidden by finishes. The collective ¨Roundabout Nation,¨ with a series of aerial pictures, documented infrastructures executed in virgin landscapes where the architecture that was meant to complete the urban operation never arrived and the roads and roundabouts remained as isolated geometries scattered throughout the territory.

The collective ¨Roundabout Nation,¨ with a series of aerial pictures, documented infrastructures executed in virgin landscapes where the architecture that was meant to complete the urban operation never arrived and the roads and roundabouts remained as isolated geometries scattered throughout the territory.

The power of these photographs is intrinsically linked with a strong element of criticism, but besides their political position toward the system, these snapshots, captured in different moments of the construction process, have the astonishingly evocative capacity of freezing an early stage of architecture, when the work is not yet finished. Only the evolution over time will reveal the success or failure of the operation. The contemplation of these ruins not only reveals the minimum actions necessary to complete the construction process, but also suggests a reflection on their behavior over time. Ultimately these images attempt to elaborate on the idea of unfinished architecture.

The dictionary indicates the following synonyms of “unfinished”: unadorned, crude, formless, imperfect, raw, rough, under construction, unfashioned, unperfected, unpolished, unrefined. All of these adjectives conjure in the imagination of designers a type of architectural intervention that perceives the existing built environment as a constraint upon which we can leave an important but impermanent mark. In this way, architects become a link in the chain of a structure’s life. Through the concept of the “unfinished” we may understand the desirability of a perpetual state of evolution of the constructions that define our societies. The architecture of the unfinished leaves a door open to the unexpected, and to ideas and interventions of the future, many of which we may not yet be aware of. Unfinished architecture blurs the signature of the architect as an author and transforms the piece into a collaborative work that involves actions over years of use.

The original trace of Diocletian’s Palace in Split could be considered as a project that ended in the fifth century with the construction of the residence for the Roman emperor. However, it is more interesting to understand it as an unfinished project that began with the definition of the floor plan of the palace and still today continues serving as a master plan for the city. An aerial view reveals the rectangular perimeter of the palace as well as its ancient main halls which are today transformed into piazzas, public buildings and other urban spaces. The houses that have been built over the years since the fall of the Roman Empire, instead of starting from scratch, assumed the remains of the palace as found objects available for reuse. The layout of the palace originally responded to the functional individual needs of the emperor, but also was sufficiently generic to allow its transformation throughout the following centuries into a construction that today belongs to the public realm.

When we examine the notion of ¨Unfinished¨ throughout history we discover examples that demonstrate the role of the architect in society not as a designer that starts from scratch but as an analytical mind that examines the existing environment in order to discover constraints upon which to build a new mark. This is especially obvious during the Baroque period in Rome.

The Baroque architects’ reaction toward the ruin was that of true artists who recognize and respect the ruins not as untouchable monuments, but as elements that are still active in the present. The layout of Piazza Navona is based on the plan of the Roman Circus that previously occupied the same space. Instead of adopting a protectionist attitude by filling the piazza with ancient columns and excavated stones, the Baroque architects granted the Romans the supreme honor of inspiring their designs through the incorporation of the imprint of their buildings.

The fact that the plan only served as the constraining geometry for the new design does not represent any lack of respect for the Roman ruin, but rather a creative attitude that understands the ancient city as a living context susceptible to being used and reinterpreted from an artistic point of view instead of as a museum of dead monuments from the past. A similar understanding of an architecture that arises from the consideration of constructed yet unfinished elements can be noted in other urban spaces, such as Piazza di San Ignazio, Piazza di Spagna or the Quai di Ripetta in Rome.

The fact that the plan only served as the constraining geometry for the new design does not represent any lack of respect for the Roman ruin, but rather a creative attitude that understands the ancient city as a living context susceptible to being used and reinterpreted from an artistic point of view instead of as a museum of dead monuments from the past. A similar understanding of an architecture that arises from the consideration of constructed yet unfinished elements can be noted in other urban spaces, such as Piazza di San Ignazio, Piazza di Spagna or the Quai di Ripetta in Rome.

We can also recognize reactions toward periods of scarcity in the reuse of pieces from previous constructions. Especially interesting is the period in history when the concept of style was not important and architectural elements, designed originally according to one particular stylistic direction, were reused to complete another building. The beauty of Santa María in Trastevere is linked to this juxtaposition of fragments from previous constructions.

Inhabitation becomes a critical question to evaluate the success of certain urban operations, originally designed with one purpose, but modified over the years to respond different needs of society. Henry Hope quotes the writer Auguste Hare, who claims that between 1870 and 1903 archaeologists destroyed more of the artistic beauty of Rome than the Goths or the Vandals in any of their invasions. Hope renders this reality by comparing two engravings: one of the Roman Forums in the seventeenth century, and another after the archaeological excavations of 1935 ordered by Mussolini in the Via di Fori Imperiali, which unearthed columns and remains of ancient temples that had been buried repeatedly by the constant overflows of the Tiber River. The rows of houses, the tree-lined avenues and the quaint adaptations of the Roman monuments occupied by humble programs shown in the first engraving had all disappeared in the second. The magical space represented in the scene, where passersby could walk in close proximity to the capitals of the buried temples, was lost. In the second perspective, the fragments of the Roman ruins have been cleaned up to remove any trace of occupation. The ruins have been converted into mere objects of contemplation, generating the desolate landscape of a bombed-out city inhabited only by tourists.

The Italian expression non finito is used to define artistic expressions whose value resides in their unfinished condition. In some cases the incompleteness of the work is produced voluntarily by the author, while in others technical difficulties impede completion, or even the unexpected death of the artist. At some moment the author’s intent meets with an unexpected event that humanizes and contextualizes the artwork. We can find examples in painting and sculpture by important artists such as Leonardo or Michelangelo. Architecture is not too far removed, if we observe the variables that can occur during the design and construction process that modify the author’s initial intentions. These interferences are opportunities to understand up to what point, far above the specific needs of the client, architecture belongs to society and therefore should evolve along with the culture willing to respond to future needs.

Cave di Cusa is located three kilometers south of Campobello di Mazara in the Italian province of Trapani. This quarry was first used in the sixth century BC to extract the stone for the temples of Selinunte. With the arrival of the Carthaginians led by Hannibal the quarry was abandoned abruptly in the year 409 BC. It is still possible today to observe the original rock sculptured into cylindrical forms, in an early stage before becoming a column in a temple that was never built.

The unfinished obelisk of the city of Aswan (Assuan) would have been the largest element of cut stone in the world, if it had not been fractured during the quarrying process and therefore abandoned. The work could never be completed, but like the stones at the Cave di Cusa, a perpetually unfinished object was produced as the result of an unexpected event.

These stones never left their place of origin and were never used for their intended purpose, however their unfinished condition reveals a phase in the quarrying process that we would otherwise never have known.

These stones never left their place of origin and were never used for their intended purpose, however their unfinished condition reveals a phase in the quarrying process that we would otherwise never have known.

But besides reporting this situation in response to the main call, it was important to illustrate how architects have been dealing with this period of economic scarcity.

“Unfinished” proposes to draw attention to the process and not only the result and to view architecture as unfinished, in constant evolution and as something that serves humankind, in a moment of uncertainty with respect to the profession which makes this an especially relevant consideration for our time.

The ultimate goal of the “Unfinished” exhibition is to present a selection of built works developed during these years of scarcity where the economy of means has triggered unexpected and ingenious solutions. Some of these offices have demonstrated how creativity can be used as a powerful tool against economic constraints and can subvert the negative aspect of the crisis to develop an architecture that is no longer linked with the concept of spectacle.

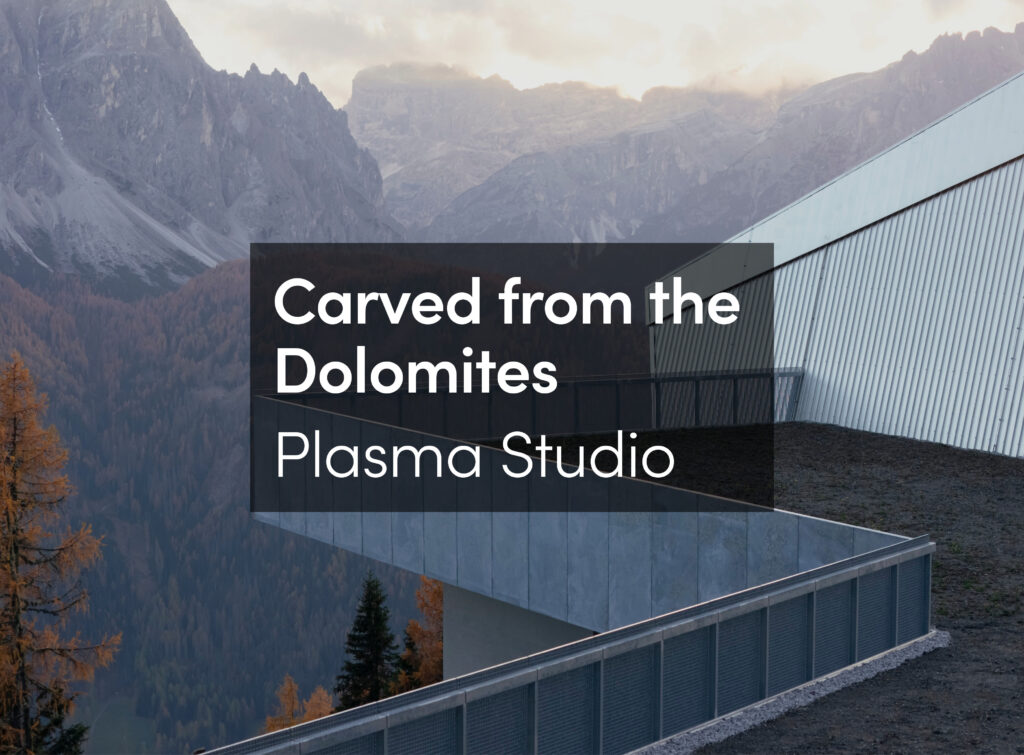

The fifty-five architectural interventions exhibited in the perimeter spaces of the Spanish Pavilion were selected in an open call where more than 500 works were presented. They epitomize a way of understanding the constructed environment as unfinished and in constant evolution. The economy of means compels us to modify design strategies, sometimes through simplification and at other times by incorporating previous structures or anticipating future adaptations. Architecture without place (because there is no more real estate), without its own facade (because one already exists), without its own structure (because it consolidates and uses the existing one), without new spaces (because it reuses the old ones), without a single author (because it is the result of the work of many people), or whose beauty arises as a result of yielding to difficult initial constraints that limit possible actions.

The selection of these built works responded to the open call that was framed under the Unfinished Manifesto:

-Unfinished Architecture blurs the signature of the architect as an author and transforms the piece into a collaborative work that involves actions over years of use.

-Unfinished Architecture defends strategies of adaptation, transformation and occupation of abandoned or incomplete structures that are taken as a given constraint, allowing unexpected solutions.

-Unfinished Architecture examines typologies that became obsolete after the difficulty of adaptation to fulfill new demands.

-Unfinished Architecture defends demolition as a powerful tool to architecturally intervene in our cities.

-Unfinished Architecture defends the consideration of the future ruin of the building.

-Unfinished Architecture examines how certain architectures are more likely to be considered as part of a chain that could be continued by others.

-Unfinished Architecture analyzes how the cost of a building should be considered in relation to its life span.

-Unfinished Architecture promotes dialogue between the old and the new.

It is the intention of this book to expand the content of the “Unfinished” exhibition, recognized with the Golden Lion as the best national pavilion at the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale. Fifty-five photographs from seven different artists, fifty-five built works addressing nine categories of Unfinished, eleven interviews with relevant voices in the academic context and five critical articles are contained in this book.

It is not the goal of this compilation of ideas to conclude with certainties, but rather to keep the conversation open.