A rocky island stands on a windless seascape. Tall cypress trees occupy the dark inlet, where steep cliffs are pierced on all sides by enigmatic rectangular doorways. Small white terraces and walls emanating an unnatural light, complete the architecture of the island. The place appears uninhabited. Only two figures on a boat, an oarsman and his passenger dressed in white, ferry what appears to be a sarcophagus covered in cloth.

Completed by Swiss painter Arnold Böcklin in 1880 and quickly nicknamed by the author Die Toteninsel (the Island of the Dead), over the years this large canvas has become one of the most popular romantic paintings in Europe, capturing the imagination of Dali and Rachmaninoff, De Chirico and Hitler. The strange subject matter and execution of Die Toteninsel offers an image at once peaceful and eerie, meditative and hermetic. The seductive and mysterious shape of the island attracts and disturbs, raising questions of isolation, ritual and the afterlife.

The work was commissioned by widow Marie Berna who, after the death of her beloved husband, was looking for ‘ein Bild zum Träumen’, a picture over which one could dream. By embodying a process of grief, Die Toteninsel was then made as an object of contemplation, inviting our imagination to wander into slumber. In the painting all coordinates of time and space appear to stand still, and even movement, implied by the boat in the foreground, becomes a construct.

Correspondence between Arnold and Maria however suggests that, at the time of the commission, the painter was already working on a similar subject: a way to represent and evoke a dark and reflective mood.[1] Perhaps Böcklin considered death to be more vibrant than life, as testified by the epitaph on his own tombstone: Non Omnis Moriar—I shall not wholly die. Indeed, despite being often described as a landscape painter, Böcklin was mostly interested in depicting states of mind, rather than natural environments. Apparently, he had a phenomenal visual memory and worked primarily out his own painterly recollections. According to Mitchell Frank, Böcklin’s art was worked out of a causal sequence of perception, memory and imagination.[2]

Die Toteninsel is a design of the mind, and its tectonics look and feel unmistakably artificial. The compositions of trees, rocks, sky and sea offer a careful balance of shapes and colors, all fitting in the canvas at a strangely human scale. In addition, large portions of Böcklin’s island appear excavated and made to use through bright walls and parapets, deep doors and galleries, producing what is actually a profoundly humanized scene. In this respect, Die Toteninsel can be described primarily as a built environment, generated through Böcklin’s illusionary mode of artistic production.

Dreams in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

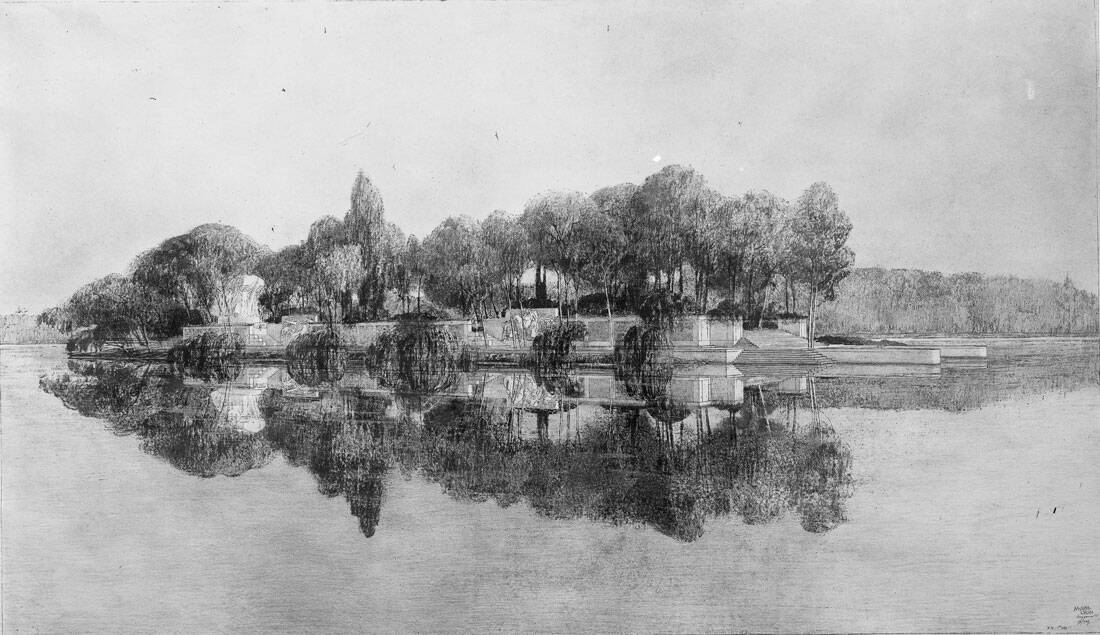

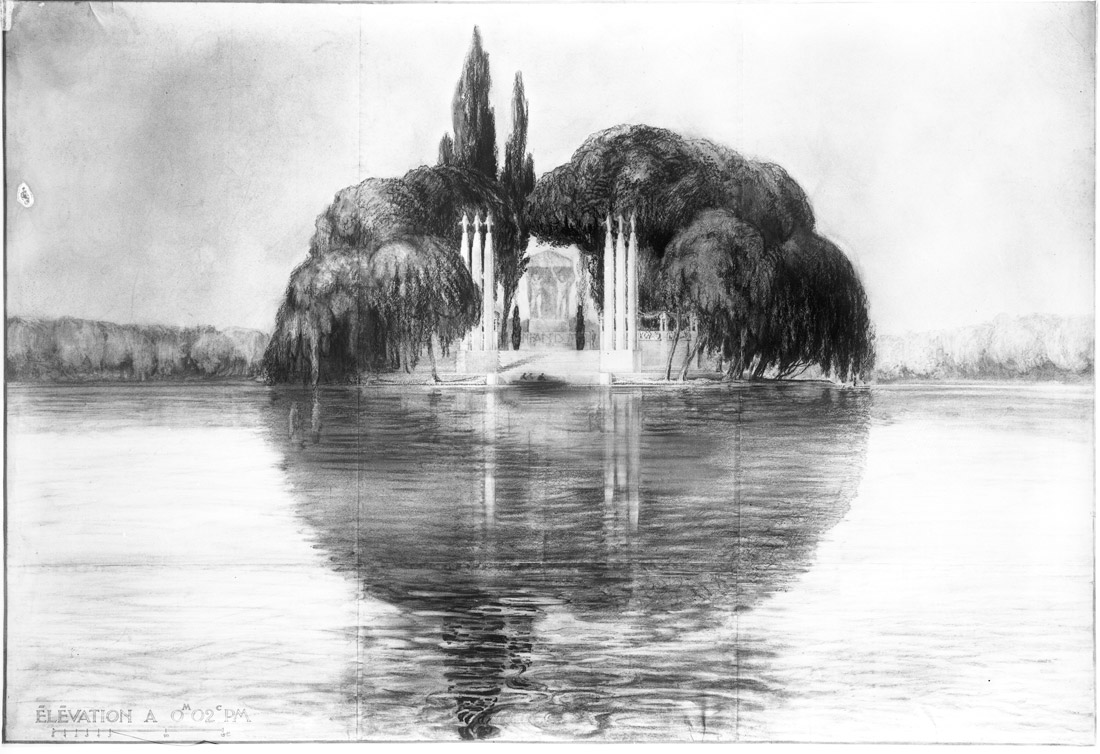

Alongside its theatrical subject matter, the painting’s life acquired a unique popular significance thanks to its replication. During the 1880s, while residing between Florence and Zurich, Böcklin made four more versions of Die Toteninsel: in 1880, 1883, 1884 and 1886. While all are evidently iterations on the same subject matter, they also look expressly different. In 1883 Böcklin redesigned the imaginary shape of the island into a walled enclosure, with multiple stories, a more prominent docking and a colder, more contrasted atmosphere between the bright rocks at daytime and the dark cypress forest in the middle.

The last version Die Toteninsel then appears to operate a sort of synthetic dramatization of the entire sequence, where the setting is at once warm and hostile and the distinction between sea and sky becomes undefined. Moreover, the very purpose of the island is unclear: a window appears on the left side of the cliff (who is that for?), and it becomes impossible to tell whether the boat is moving toward or away from the island.

During the 1880s the isolated Toteninsel turned into a sort of archipelago. Rather than having a geographical connotation depending on morphological features, this is an archipelago of dreams, where each island shares with the rest a common imaginative origin, generating a visionary ensemble of unique yet interconnected states of mind.[3] Through his nearly decade-long obsession with his islands, Böcklin produced a pre-modern family of facsimiles, with no originals and no copies, but instead all reproductions of the author’s psychology of a ritualistic afterlife.

During the second half of the 19th century Böcklin’s oeuvre, which often explored themes such as death and ruination, became very successful with the German Bildungsbürgertum, the educated middle class, thanks to his compromising attitude towards the classical tradition, as well as a certain painterly platitude. Die Toteninsel was especially popular thanks to a further stage in its multiplication. After the third of Böcklin’s paintings, in 1890 German artist Max Klinger made a free copy for one of his etchings, turning Böcklin’s canvas into an object mechanical reproduction.

Klinger’s homonymous 6,12-by-77,7cm aquaforte etching was distributed at a convenient price to wealthy families across continental Europe, turning the composed and intimate setting of the dead island into a truly international phenomenon. Apparently by the turn of the century there were very few respectable middle-class European families without one of his islands in their home[4]. Thanks to the necromancy of infinite reproducibility, Die Toteninsel became an ‘icon of world pain’, an immortal manifesto to its own tectonic immediacy. From the privacy of an imago mortis, soon after its production Die Toteninsel acquired a unique afterlife as an archipelago of mass-produced architectura mortis.

The Failure of Architecture

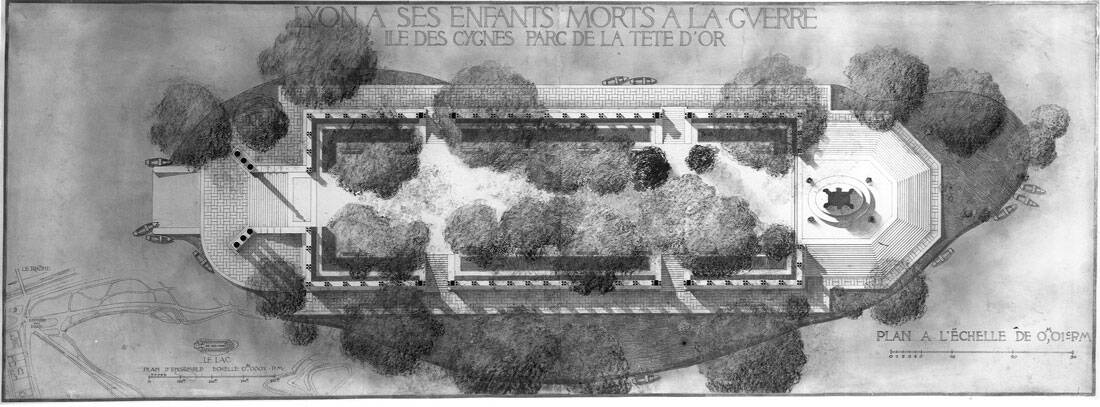

In 1921 Tony Garnier, the father of the Cité Industrielle, completed the design for a memorial to the Lyonnais victims of WWI, which was erected in 1930 on the Île des Cygnes at the Parc de la Tête d’Or in Lyon. Garnier’s project consisted of an embankment, a large stair and a wooded promenade leading to a giant cenotaph in the middle of the islet. Clearly evoking the atmospheric nuances of Die Toteninsel and more or less directly inspired by its forlorn aesthetic—and in fact immediately nicknamed l’Île des Morts—, Garnier’s island actually goes beyond a visual resemblance and instead tries to concretize the deeper essence of Böcklin’s collection of islets.

Rather than a remote space for collective reverence, the Île is a profoundly non-religious answer to the architect’s own obsessions over time and death, an end product to his numerous design iterations (eight in total) and countless drawings. These drawings tell a story of a profoundly explorative process, not unlike Böcklin’s own research, into the emotions and psychologies of grief and remembrance. However, once put into stone, the narratives of Garnier’s design process were inevitably lost—architecture’s eternal sacrifice.

Once removed from its illusionary settings and from the imaginative world of visual art, Garnier’s Île ceases to evoke anything remotely belonging to the fantasy of Die Toteninsel. Once built, the island meant nothing in itself, and its very raison d’être was erased soon after completion by the construction of a public tunnel connecting it to the mainland, hence cementing its inherent contingency as a place of public urban access. The Île des Morts became a prosaic, almost banal attempt at translating Böcklin’s imaginative world outside reality.

Robin Evans noted how ‘Drawing in architecture is not done after nature, but prior to construction; it is not so much produced by reflection on the reality outside the drawing, as productive of a reality that will end up outside the drawing.’[5] We may recognise the value of Böcklin’s paintings as the imaginative object of a dream carried outside our minds. Die Toteninsel is a project-ion, showing how, in a way, design can come from a state of vigilant dreaming. Garnier’s project, in turn, demonstrates how building can be a form of solid awakening. If Die Toteninsel stands as an immortal statement to the possibility of imagination, the Île des Morts constitutes its conscious and rational counterpart.