In 1978, Alaba International Electronics Market was squeezed out of Lagos, dumped on a swamp and left to its own devices. Since then, the market has grown to include 50,000 merchants that net over USD 2billion annually. Officially described as an “unorganized sector”, Alaba accounts for 75% of West Africa’s electronics trade.

Like most of Lagos’ peripheral markets, Alaba is an orphan. Begun as part of Mushin’s Alake market, Alaba had little significance until its electronics merchants started selling speakers in the 1970s. As music amplification became more popular, the market took off, moving loads of original, reconditioned and sometimes bogus Panabis, Gibson and Philips speakers through its many stalls. The ’77 FESTAC event raised demand for audio speakers at the same time that it put pressure on the market to move away from its busy neighbor, the National Stadium. So Alaba began a westward exodus. First, it went to Mile 2. But that location only exacerbated the event’s effect on the market because by increasing the traffic exposed to the merchants at the same time that it increased the merchant’s proximity to the Apapa Port supply. Later that same year, the market was moved further west along the Badagry Expressway, to the small jungle-enclave of Ojo.

Chief Magnus Ubochi, chairman of the market association, says that the move to Ojo was crucial, giving Alabans “a place where they could grow to infinity.” [1]

And they nearly did. “Little Japan”—as Alaba has been dubbed—was adopted by the Badagry Local Government Area in 1979. Combining itself with the local electronics market, the 2,800 displaced Alaba traders soon had the second largest market in Lagos State, and far and away the most profitable one. A large fire and the austerity measures of the 1980s weakened the market’s activities as the importation of consumer goods was minimized. But parallel trade with Benin and new concrete lock-ups buoyed Alaba through the eighties, establishing an operating formula based on circumvention of traditional supply chains and vigilant self-defense. In the mid 1990s the Nigerian Port Authority relaxed its import tariffs, enabling Alaba to benefit from two supply sources nearly equidistant from the market site: the (official) Apapa Port and the (unofficial) Benin border town of Seme.

Straddling the two sectors maximized the market’s responsiveness to supply-side opportunities, and it soon became the largest electronics market on the continent.

Alaba used this success to build a town around itself. Generating huge revenues for the Ojo Local Government Council, the market has earned a reputation as the region’s source for “second-class or fake electronics” imported from Asia. This reputation, however, has not handicapped business. The Alaba Market Association recently raised N50 million to build Ojo an “ultra-modern secretariat and car park.” The Association also donated the books and television sets that fill the market-funded local library. Ojo’s fire station, electric substation and even telecommunications tower were constructed at the Market Association’s expense. [2] Outsourcing domesticity to the surrounding area, Alaba has effectively transformed its host town into a bedroom community.

Left alone, Alaba International Electronics Market has sustained rampant growth. And, left alone, it has had to reconcile this runaway expansion with increasing vulnerabilities. After an initial big-bang and several years of capitalism-without-Keynes, the market is becoming self limiting. It is now building its first fence—a 23 million naira wall to separate the market area from its host city. Having consolidated its edges, the market has had to adopt alternative strategies to grow. In addition to building vertically, Alaba is metastasizing: mini-Alabas have turned up at Oshodi, Mile 12 and, most recently, Abuja. Backed by an American investment company, the 600 plot Abuja electronics market is being laid out on 20 hectares along the capital’s spine, Airport Road. It will be named “Alaba New.”

Not a City

Alaba looks like a city. A “total self help effort”, the market has generated its own system of address, its own type of street, its own provision of churches, its own banks, its own brand of democracy and even its own form of justice.

But it is a city without housing, without women (the market is almost exclusively male) and without children. It has no nightlife because it has no night: its “hours of operation” are from 8am to 6pm. It is, of course, closed on Sundays.

As a business, Alaba acts on its own prerogatives. The Market Association funds itself with a monthly security levy, donations by executive members, and fines collected from unscrupulous merchants. In turn, the association gives money to the local government, the poor, and even takes care of its past leaders. The DIY effort funds borehole drilling, latrine construction, and public telephone booths. The association is paying for the new perimeter fence, television towers, street gutters, electrical transformers, a telecom system and even a security vehicle to patrol the market. But the Association does more than just service the market with infrastructures; it’s also building a new secretariat and courthouse. Members of the group have developed new, more vertical building typologies to increase market densities. New stall types integrate a warehouse on the first floor with an office on the second; merchandise is kept in the first floor lock-up from where it can either be loaded directly onto transporters or set out on display. That is, the shops are both wholesale and retail outlets.

Alaban Pangea

The market site is organized in three divisions: the “fancy section” (lights, lampposts and electrical fittings); the “electrical materials area” (transformers, wiring, bulbs and spare parts); and the “pioneer market” (appliances, generators and circuitry). Nearly 50% of this merchandise is secondhand—brought in from clearinghouses in the Middle East, Europe and Asia.

The preponderance of used goods has led to parallel industries of near-manufacture that operate across the market’s sections. Reducing the bogus, spent, or out-of-order appliances to heaps of circuitry, transistors, and plastic shells, entrepreneurs organize whole alleyways into mechanical assays. A production line of electricians, welders, painters and technicians then works in tandem to produce electronic hybrids of pieced together radios, TVs and generators. Not so much a factory, the secondary market is more a disassembly field within which all things have different values assigned to them: mechanically functioning BUs (Built-Ups) and nonfunctioning but potentially valuable parts or CKDs (Complete Knock Downs). [3] These material movements occur between sections, across streets and alongside buildings. As the market thickens, its interstices become increasingly productive.

These gaps aren’t just leftover slack space. Alaba never had a plan to abandon, or a spectacular failure to celebrate. Perhaps this is because Alaba is predicated on terrain, not streets; its structures are more closely tied to landscapes than cities. Although it is provisionally bound to the line of the highway it straddles, the market benefits from patterns of circulation and communication that are irrespective of any road. Many of the market buildings are not fronted by a sidewalk or curb. Instead, all scape is equally navigable by pedestrian, wagon or truck. Material movements in the market vary tremendously in scale: huge shipping containers vie for space with circuit-filled buckets. The indeterminacy of the road’s breadth allows a maximum number of things to happen on it. At Alaba, a road might have generators, aggregate piles, parked cars, inventory, waste and even a portable prison adjacent to one another.

A disciplined skyline matches the free-for-all on the ground plane. The first generation lock-ups are single-storey CMU structures with 10×10 and 10×20 footprints. The lock-up performs only one function: it protects merchandise. In turn, merchants bring their own infrastructures to this basic shell.

Alaba is said to have the highest concentration of generators in the world. Portable generators are propped up on tires just outside the lock-up doors, while larger fixed units are put in welded rebar security cages and left in the street. Communications systems are also left up to the stall owner.

On approach, the market first appears as a thousand makeshift radio towers swaying way above the rooftop’s satellite dishes. All hoopla about cellular toting nomads leapfrogging into the twenty-first century is immediately checked. The Alaba system is as successful as it is perverse: because communication is the crux of trade, merchants spend huge sums on private radio-wave towers to insure cellular access. Attempts by telecom operators like EMIS to consolidate the market’s network with base stations and shared antennae are met with skepticism.4 In a business that directly sources inventory from markets in Singapore, Taipei, London and Dubai, the telecom masts are a necessity. If networking has formal consequence, this is its apotheosis.

Not a Tribe

At Alaba’s center are its two most public institutions, each imposing different aspects of discipline—one psychological and one political. The first, a blue Pepsi (“The Choice of a New Generation”) ship container riddled with irregularly shaped, rebar-grated holes, is the town prison. It sits conspicuously on the main street that passes through the market. The second, a simple shop, houses the International Market Association Electronics Alaba (IMAEA) court. It is inconspicuously located just opposite the prison.

A legion of uniformed and plain-clothed security personnel operates between the punitive and judicial branches. The IMAEA has put the two ends of Nigerian law enforcement trade to work on the same beat: the vigilante and the rent-a-cop. What in other contexts would remain at opposite ends of the legal spectrum are here brought under the same umbrella. Having the two systems in place increases the market’s stability by keeping the two patrols suspicious of one another. What’s more, the association regularly cycles through both area boys and private security companies to keep temporary alliances from forming between criminals and the patrols. When infractions are identified, perpetrators are either held in the prison or taken directly to the court and dealt with by representatives of the IMAEA. Hearings are held on Fridays.

It follows, then, that the largest committee of the Market Association controls punitive measures: the IMAEA calls it “The Task Force”. But this committee is only one of a long list of IMAEA groups that regulate market activity; it should not, for example, be confused with the similarly named “The Tax Force.” Although a chief leads the market, it is hardly a tribe.

The chief is elected for a three-year term, and is allowed a limit of just two terms. The larger organization is made up of a 40 member executive council consisting of business leaders, the more authoritative elders council and 10 elected officials that head the various “departments.” These include a development committee, a finance committee, a public relations department, a publications department, an electricity committee, the tax and task forces, a works and development committee, a security department, and even quality control groups and trade organizations. [5]

These council groups are, of course, complimented by sub-committees. The Electrical Dealers Association of Nigeria, EDA, a trade group associated with the IMAEA, was formed to pressure the Apapa Port Authority to control the number of counterfeit and fake products coming into the country. Fake products are bad for business—or at least the publicity associated with them is. Mr. Celestine Obioguatu set up a sub-committee within EDA to tackle the PR problem. To get at the problem directly, he insisted on creating a third tier of acronym—the Anti-Adulteration Committee (AAC); the AAC reports to the EDA, which in turn reports to public relations department of the AIEA. The AAC has the power to enforce market laws against fakery. In its first year of patrols, the Anti-Adulteration Committee seized and then burned over 185,000 naira worth of bogus electronics. The EDA implores prospective buyers to visit their secretariat for inquiries into the pedigree of the market’s products, and even offers limited warranties on electronics bought from its member stalls. [6]

In “A New Paradigm for Urban Development”, a paper delivered at a World Bank conference in1991, A. L. Mabogunje proposed that the lines between the informal and formal sectors contained the greatest potentials for new urbanisms. Calling for “institutional radicalization,” the very figure of old-guard African urbanism suggested that temporary fusion between informal processes and “mature” institutions might be read as a blueprint for progressive urban strategies. [7] As ambitious as such a suggestion might be, Alaba is already there. In fact, Alaba doesn’t just enable the “temporary” sector-bridging that Mabogunje proposes, it hardens such arrangements. They become durable, not radical; the IMAEA is everyday evolving a more and more dynamic relationship with mature institutions.

Banks, for example. In the last ten years, 21 lending institutions have formed in the market. Aside from providing seed loans and micro-credit services for aspiring electronics dealers, the banks have become part of the market’s operating system. By maintaining a database of each vendor’s performance, the lending institutions are able to alert the IMAEA of its member’s activities. Transgressions and discrepancies can be identified and punished, and successes rewarded. The market association depends on these databanks to make forecasts and develop policy. In turn, the banks rely on the market to design and establish loan structuring schemes specific to the area’s merchants.

Scouting

“The Japanese experience in imitative technology cannot be easily duplicated but is instructive. The country should be prepared to pay the high cost of modern technology and management. Our laws on patents and copyrights are premature. We should, with a sense of urgency, encourage and condone industrial espionage and piracy.” [8]

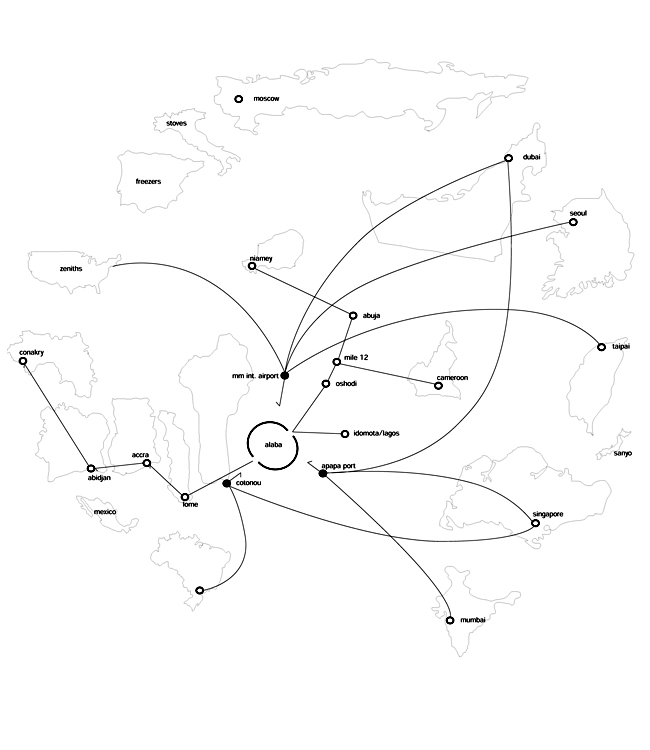

Mimesis is part of the Alaba formula: find your best men, give them plane tickets to Taipei, Moscow, Singapore, Mexico city, Sao Paolo and Dubai (the Klondike of free market success) and have them take notes. To go to Redmond, Palo Alto or even Tokyo (in 2000 at least) would be a waste of time.

Chief Ubochi calls these mercantile prospectors his “boy scouts.” The scout scans the globe on market-funded missions of capitalist reconnaissance.

In this way, the IMAEA continually updates its operations with emerging models of late/post capitalism based on other sector-straddling markets in Southeast Asia, Russia, and, most recently, the Middle East. These markets are all at the forefront of what Mabogunje had termed “fusion” and what others might call corruperation.

Alaba has long recognized the advantages of being between sectors. Even geography reinforces its position. Being between Apapa port and the Benin border means that it can be between official and unofficial—direct and parallel—trade routes. This increases the number of supply channels it can rely on. As good as these sources are, however, the last ten year’s phenomenal growth is more the consequence of a third channel: the airport.

“We are connected globally,” says Ubochi, pointing to the sky. If a lot of cheap Sanyo stereos comes up for bid in Singapore, Alaba’s corps of scouts goes to Singapore. If a wholesaler folds in Delhi, they go to India to clear any remaining stock. The 30 to 50 containers a day that arrive at the market are filled with new and used goods from Singapore, Malaysia, South Korea, Taiwan, China, Italy (gas cookers), Spain (freezers), and the United Arab Emirates (video games, generators). Japan used to be on the list but has been dropped for the simple reason that Lagos-Tokyo flights have become prohibitively expensive. To compensate, Alabans get their Japanese products in the United Arab Emirates.

Doing Dubai

On Friday, Jan. 30, 2000, a Kenyan Airlines plane carrying 134 Nigerian passengers crashed in a lagoon outside of Abidjan. Coming inbound from Nairobi, the plane was unable to land in Lagos because of the Harmattan dust that forced it to continue on to the Ivory Coast. Five Nigerians survived the crash. The casualties were victims of an increasingly popular and important air-route between Lagos and Dubai. Most of those on the flight were merchants of the emerging “suitcase trade” between Africa and the free trade zones of UAE’s commercial capital. [9]

In the last five years airlines have dramatically stepped up their frequencies of flights between Dubai and the major sub-Saharan trade areas of Johannesburg, Lagos and Nairobi. The UAE’s own Emerates Air is leading this market: the carrier’s freight division, Emirates SkyCargo, has projected a 24 percent increase in both revenue and tonnage for the 1999-2000 financial year on routes that can move goods from the Far East to East Africa in less than 24 hours. Dubai’s logistical prowess has actually led to a regular flow of Eastbound vegetables in one direction and Westbound electronics in the other. [10] Similarly, Kenya Airways is planning a 100 percent increase in frequency, with a total of four weekly flights, from Dubai to Nairobi with connecting flights to Lagos and Johannesburg. And, Nigeria Airways made Dubai its regional hub in 1997. [11] Air travel between Lagos and Dubai is largely the domain of the Igbo businessman—the Alaban or spare parts dealer attracted to the Gulf’s enormous secondary of used computers, peripherals, and other electronic goods. Dubai papers are filled with lists of second-hand goods for sale. Such merchandise has a kind of mythic status in Lagosian markets. Called “tokunbo”—Yoruban for a child born abroad—the used goods instigate many secondary and tertiary material cycles that recuperate or recycle products. Like Alaba, Dubai’s many Free Trade Villages have high percentages of out-of-date electronics. Just as Alaba fashions itself after Dubai, Dubai once fashioned itself after Singapore. The development of Dubai dates back to the 1960s.

As Sultan Ahmed Sulayem, chairman of Jebel Ali and managing director of Dubai Ports Authority puts it: “(a)t that time, we were fascinated by what Singapore was doing in developing its port. So we sent people to Singapore towards the end of the 1960s to see what we could learn.” The plans remained on the drawing board as the country did not have the necessary funds to “translate them into reality” until the discovery of oil. Money generated by the country’s abundant petroleum reserves was sunk into huge infrastructure projects including the Jebel Ali Free Trade Zone.

Like Alaba, Dubai’s only real asset is its relative position: halfway between Singapore and London, halfway between Moscow and Nairobi. The city couldn’t help becoming a hub; and, of course, all hubs can’t help becoming duty-free cities. Shopping replaced petroleum as the country’s distinguishing feature as Dubai put itself on the map with both the world’s largest shopping festival and the world’s tallest hotel.

Dubai’s geography, once its greatest advantage, is now actually limiting its growth. But at the moment of its apotheosis, the Emir has rescued his emirate with a new geography—electronic space. In the year 2000 Dubai will launch itself into an electronic infinity with the christening of dubaielectroniccity.com.

Like Alaba, Dubai’s population is mostly male (70+%) and mostly from afar. Expatriates are far and away the majority in the UAE, mostly coming from the India, the Philippines and Pakistan. And like Alaba, Dubai benefits from a branded, if unbridled, form of capitalism. To attract investors, the Dubai government did the usual: the standard urban cocktail of the “pro-business package.” But to keep clients in the desert they took the off-the-shelf business package and hyperbolized its every promise. In Jebel Ali Free Trade Zone, foreign investors are not only assured 100 percent ownership, but also enjoy a renewable tax holiday for 15 years during which they do not have to pay income, corporate, building or land taxes. The Airport Free Zone has an almost identical pro-everything gist, but promises an exemption on import duties and allows the free movement of capital in addition to the standard list of freebies.

Alabas

Clifford Geertz once wrote that the informal market was doomed to archaic inefficiencies. “The trader,” said Geertz, “is perpetually looking for a chance to a make a smaller or larger killing, not attempting to build up clientele to a steadily growing business.” [12] Geertz was troubled by the bartering, haggling and “inefficient” price structuring mechanisms of informal environments. Since 1963, social anthropology has spent enormous amounts of energy describing how such systems are, in fact, based on enormously powerful and effective social organizations that are nothing if not efficient networks. The most recent cases—the Alaban conditions—present the most terrifying potentials. Unfettered, and unleashed, Alaba’s severe social program is matched by an incredibly compelling post-urban example:

“Within the globalization regime, there is an emphasis on speed, incessant signification, unimpeded capital flows, the hyper-reality of credit and fiscality, and the amplification of micro-dynamics as keys to profit. Accordingly, the deployment of new modalities of organization acting outside juridical, parliamentary and ‘moral’ constraints are increasingly required. The consolidation of all institutional life produces its marginality that is a space outside the rules and norms which must be turned to at times when the norms are unable to do so. The marginality constitutes a locus through which disparities, problems, power conflicts and procedures can be ignored, mediated or circumvented. Globalization has provided a vast new range of opportunities for economic and political actors to operate outside increasingly outmoded laws and regulatory systems, as well as to spawn new relationships among them. African cities exude an availability to these opportunities precisely because they appear outside of effective control, and thus anything could happen.” [13]

Alaba is almost nothing. Its most striking feature is its flatness. Only recently has it had to bother with the maison domino. But its skyline is still somehow striking. All around, 30 meter antennae sprout from between the market stalls. Huge satellite dishes sit precariously on puny rooftops. Cell phone ownership is incredibly high, and the country’s greatest concentrations of what would otherwise be called Mail Boxes Etc. can be found at Alaba. In fact, on an off day, when the market is empty, it looks more like a communications center than a commercial one.